by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Neo-Opsis, May 2015

I point at the star map again, angrily saying, “Come on, Meijing! We only have a few hours of air left!” But the black-masked eyes blink at me impassively, profoundly uninterested in the yellow spot on the view screen under my fingertip.

We’re only five jumps from home. Three if we didn’t have any cargo. Or one jump back down to the planet of Gloaming, but Meijing won’t jump our spaceship either way. I knew it was a risk to keep doing cargo runs this month, but I never imagined Meijing would leave us stranded like this. I guess that’ll teach me to trust a dumb animal. Even one with quantum spaceflight capabilities.

“I told my girlfriend I’d be home an hour ago,” Jace says irritably. He’s my cargo boy, and every word out of his mouth makes me feel old. I can’t imagine taking the ability to travel from Gloaming to Earth in less than an hour for granted. I remember when the scientists first discovered Gloaming, and anyone audacious enough to dream about going there was a laughable fool. Not a visionary.

Now I can look out the window of my spaceship and see the gleaming cities of Gloaming glitter along its twilight meridian. And it’s all possible because of this big, useless lump of a cuddly panda bear.

Jace offers Meijing another handful of bamboo to munch, but the panda only raises a hind paw to itch at her control collar. It’s a device that creates an electro-magnetic field that ensures all her jumps are constrained to the right vector.

I’m tempted to snatch the handful of twigs from Jace and beat Meijing about the head with it, but I don’t think that will bring my spaceship any closer to landing on a planet with breathable atmosphere. Besides, Meijing looks too much like a children’s plushie. I can’t hate her any more than I would a marshmallow.

“God,” I say, “Why didn’t they put engines on these ships?”

“Engines?” Jace asks.

He’s such a youngling.

“Yes, engines,” I say. “Engines to fly the ship back down to Gloaming.”

He blinks, confused, and I explain.

“Before pandas, spaceships had rocket fuel and engines. They were blasted through the atmosphere by giant explosions, and they flew. Like birds, but straight up.”

Jace laughs and shakes his head. He’s part of a generation that thinks quantum jumping is a perfectly normal biological adaptation. Scientists are even working on incorporating it into human DNA now. Then we won’t be so dependent on pandas and their strange moodiness every twenty months.

For the moment, however, I’m trapped in orbit of Gloaming inside a spaceship that amounts to a giant, airtight box. The only engines it has run the limited atmosphere scrubbers, the force field that forces Meijing to carry the ship with her when she jumps, the lights, and the computer where I keep records of my cargo log and Jace plays video games. It’s more of a camper than a real spaceship.

The only piece of actual space-faring technology I have is Meijing, my panda.

Pandas would have died out if the scientists hadn’t gengineered new strains of high protein bamboo for them. It’s the craziest combination of quantum mechanics and wildlife preservation ever. We’d have never even discovered that pandas have a gene allowing for quantum mechanical space jumping if we hadn’t improved their diet enough that they had the energy left over to use it. Having a carnivore’s digestive tract and a vegetarian’s diet is a real bummer, I guess.

“I’m taking her control collar off,” I say. “She keeps itching at it, so maybe it’s bothering her.” Jace stares at me like I’m crazy, but I can’t think of anything else to try. I’ve already tried pleading and bribing Meijing with every delicacy of gengineered bamboo I have onboard. She won’t eat any of it. I know from experience that this twenty-month itch that pandas get can last for days. Sometimes the whole month, and our air won’t last that long.

Besides, what’s the worst that can happen? Meijing may be stubborn and stupid, but I can’t believe she’s actually suicidal. I know her better than that. So, maybe she’ll drag the ship on a few jumps along a non-optimized vector, but that won’t hurt us. And at least it might get her jumping again.

Meijing perks up the moment the collar comes off her neck. The difference in her demeanor is subtle but instant. Before my hands are fully away, I feel the wavering gravity-like pull of a quantum jump. My stomach lurches sideways, then up, then sideways again. My feet stumble as the ship jumps once, twice… three times… I count twelve jumps in total before we stop.

Jace curses and says, “Where are we?” He’s looking out the window, and I can see green trees out there. But the sky above them is not Earth’s sky. We are not home.

Meijing scrabbles at the ship’s door, running her blunt claws noisily along the metal. I’m too busy being thankful that Meijing has finally been jostled out of her slump to realize what Jace is doing until too late. Like a well-trained human with a domineering pet, Jace opens the door and lets Meijing out.

Now I’m too busy being thankful that the air here has turned out to be breathable and — hopefully — non-toxic to give Jace the telling off he deserves.

Speechless, we follow Meijing as she lumbers excitedly into this alien forest. We dare not lose sight of her; she is our only ticket home. I hear other large figures crashing through the bamboo-like trees around us, and my heart races. But I can soon see that the other figures are pandas too. All of them.

“Is this what happens every twenty months?” Jace asks as we step into a clearing filled with pandas. “All the unconstrained pandas come here?”

“And all the constrained ones are miserable,” I say, feeling bad for all the times I kept Meijing from coming here.

For the rest of my life, I know I will never forget this sight. The clearing is filled with flowers. They’re built like hibiscus, but their petals radiate through every color from ultraviolet through infrared in a pulsating cycle. And, apparently, to pandas, they taste delicious. It’s a frenzied panda smorgasbord out there. All the pandas are running about, throwing pawfuls of bamboo leaves like confetti, and eating the rainbow flowers by the fistful. Some of them even look like they’re dancing.

“That flower must only bloom once a year here,” I say. “And this planet must have a longer year than ours…”

Jace nods. “We should bring a sample back.”

“Yeah,” I say. “Maybe it can be reverse gengineered and forced to bloom more often. Maybe we could grow it ourselves. Then Earth and Gloaming won’t have to shut down all transportation every twenty months for this interplanetary panda holiday.”

It hits me then, interplanetary. This planet. I look up at the crimson sky, filled with pale-faced moons and wonder exactly which vector Meijing followed to bring us here.

“We’ve discovered a whole new habitable world,” I say. And, unlike Gloaming, this one won’t require atmo-domes or terra-forming. While every planet we’ve discovered using telescopes has been a hostile ball of rock or ice, covered in swirling noxious gases, this one is beautiful. I could even imagine living here one day.

“How many more worlds do you think pandas know about?” Jace asks.

“Who knows?” I say. I look around at all the bundles of black-and-white fuzz, happily munching flowers around me, and I realize that the pandas are the true explorers here. Human scientists may have unleashed the panda’s potential, but human scientists didn’t discover this world. The pandas did. After all our years running cargo together, I knew it couldn’t be wrong to trust my panda. Pandas may have replaced spaceship engines, but they are more than mere machines.

“So… ” Jace says, “How are we going to drag Meijing back to the ship? How will we get her control collar back on?”

“We won’t,” I say. “I think it’s time we all started controlling pandas a little less and trusting them a little more. I’m sure Meijing will meet us at the ship when she’s ready to take us home… Until then, I’m going to explore.”

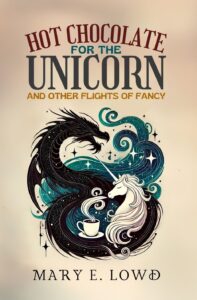

Read more from Hot Chocolate for the Unicorn and Other Flights of Fancy:

Read more from Hot Chocolate for the Unicorn and Other Flights of Fancy:

[previous][next]