by Mary E. Lowd

A Deep Sky Anchor Original, March 2023

Engleine hesitated with the upgrade chip mere millimeters from the docking port in her beloved Hansel’s head. His mechanical ear flicked, and he said, “You stopped. Why?”

“Are you sure you’re ready for this upgrade?” Engleine asked. Her own conical ears — a biological mirror of his mechanical ones — had flattened behind her long head. She shuffled her hind hooves on the floor, and her keratinous hoof-fingers tightened on the upgrade chip that would push Hansel — her dance partner and best friend — from the seeming-sentience that had fooled her into believing he was fully his own person into an actual sentient robot.

Someone who truly could be her friend.

Someone who could choose.

Someone who might choose not to be her friend.

Engleine was the one who wasn’t ready.

All that Hansel knew was that he had been programmed to dance with Engleine and make her happy, and she had been pushing him toward sentience for a long time. First, she had pushed him into taking the sentience tests, because she assured him he must be sentient. He had believed her, because he was programmed to believe her: if Engleine said he was sentient, then he must be sentient. So, he’d taken the test, but he hadn’t understood it. Mostly, the mercurial humanoid robot, Gerangelo, who had administered the test left him alone in an empty room, occasionally stopping by to say something random or vaguely insulting. Hansel didn’t mind. Hansel had known he was doing what Engleine wanted.

But he had failed. At the end of the test, Gerangelo declared Hansel to be sub-sentient.

Engleine had behaved strangely for a long while after that. She had seemed sad, and Hansel had done his best to cheer her. They danced together, performing to sold-out asteroid amphitheaters as they had always done. As he had been designed to do. But she had stopped talking to him after their shows, pouring her heart out to him. Previously, Engleine had taught Hansel that when she seemed sad, he should ask her gentle questions, until he could convince her to talk about her sadness. So, he had done that, and they had talked about him failing the sentience test and how strange it made Engleine feel to know that her best friend wasn’t anything more than a program designed to please her.

They had concluded that he should get the upgrade Gerangelo recommended.

That’s how he knew it was the right thing to do. It was what would make Engleine happy. So, when she asked if he was sure he was ready, of course, he answered, “Yes, I’m ready.” Why wouldn’t he be? How hard could it be being sentient? Especially since it simply involved slotting one more chip’s worth of processing power into his electronic brain. All he had to do was sit still and wait for the chip to slide into place.

After another moment of hesitation which Hansel patiently forbore, he felt the upgrade chip click into place.

And instantly, everything grew a million times more complicated.

No, not a million. That was an exaggeration. He could calculate the extra degree of complexity added to his brain by the increased processing power of the upgrade chip — in fact, he had known the exact number before it clicked into place — but the number had given him no concept of how it would feel.

How it felt.

Hansel had always had feelings. He’d been happy when Engleine was happy; happy when he danced well for her; happy when he knew that he was fulfilling his mission of being her dance partner. He’d been sad when she was sad, and that had motivated him to find ways to make her happy again.

But now?

He couldn’t tell how he felt anymore. Happiness felt clouded with uncertainty — why did Engleine’s happiness make him happy? Was that enough? Shouldn’t he find happiness of his own? Should he be angry at her for controlling his emotions with the power of her emotions? Did he want to have his emotions so completely beholden to someone else?

And sadness had become strangely tinged with… triumph? Or pride? Entitlement? If he was sad, then shouldn’t Engleine make it her goal to cheer him up? Was he not deserving of a reciprocal role in their relationship? Was he not an equal partner?

Of course he wasn’t. That’s what those other robots he’d overheard talking to each other outside the offices of the sentience tests had been saying: robots don’t get treated equally, even if they are sentient.

And yet… He hadn’t been sentient, and Engleine had helped him become sentient. Surely, that was because she loved him. Hadn’t she done her best to treat him like an equal, even when he hadn’t been one?

This was too many questions. Hansel didn’t want this many questions flitting through his brain.

So far, he didn’t like being sentient very much. Mostly, he wanted to yank the upgrade chip back out of his brain and make the questions stop. He wanted everything to be simple again.

But then, he would be simple, barely more than an object — a mechanical equine dancer, built to be nothing more than a mirror for Engleine who was true and real.

She was true and real.

She had always been true to him and treated him like he was real. He loved nothing more than seeing her dance — her long mane flowing from her head as she whirled and pirouetted across the dance floor, returning, always returning to his arms. Because she belonged in his arms — they’d been made for her.

Hansel and Engleine may not have been made for each other, but he had been made for her.

And she wanted him to be more.

He could be more.

He would survive the questions.

Let them buzz through his head. Hansel knew the answers to all of them: he loved Engleine, and she loved him back. They would dance together. And they would be happy, even if happiness felt infinitely more complicated now than it had before.

Hansel turned his long, mechanical, equine head towards Engleine. He saw worry in her eyes, but he smiled at her and the worry melted away. She smiled back at him, relief clear on her face.

And his own worries melted away too. Only a moment had passed since the upgrade chip had clicked into his head.

The questions and uncertainties had come upon him like a storm, and then they’d left just as fast. He was sure they’d return again, but he would weather them. Because that’s what sentience was — being too smart for your own good, smart enough to worry about things that don’t need to be worried about, and also, smart enough to let those worries go and keep functioning.

Keep dancing. Together.

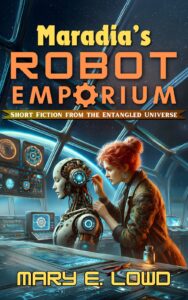

Read more stories from Maradia’s Robot Emporium:

Read more stories from Maradia’s Robot Emporium:

[Previous][Next]