by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in The Lorelei Signal, July 2022

Quiley didn’t feel like anything was wrong. She put one paw in front of the other; she kept moving. She kept playing and splashing in the river like an otter is supposed to. But everyone kept saying how sorry they were. How hard it must be. It was almost like they thought they knew something about her and Pia that she hadn’t known herself.

Sure, she and Pia had both liked to sunbathe on the same wide rock overlooking the nearby rapids, and they’d gone foraging for blackberries together every summer since they’d both been kits. So what? They each had more of a sweet tooth than most of the rest of the Roaring Blue Bevy. Or they had. Now it was just Quiley who loved blackberries to distraction.

Well, more for her.

She didn’t mean that. She knew it was sad — heartbreaking even — that Pia had died so young. And so unnecessarily. The worst part was that the Elders Council hadn’t learned their lesson. They hadn’t learned any lesson at all, and the dangerous water slide made from felled trees stolen from a beaver family, precariously balanced on a series of boulders as big as grizzly bears, was still under construction.

That beaver family had ties to the mountain lion clan, ever since the unlikely marriage between the beaver prince and the mountain lioness princess. They’d be coming for those felled trees. And they’d be coming with lion claws, not only beaver teeth.

When Quiley thought about it, she felt bleak, like everything was pointless. But surely, every reasonable otter felt that way? Surely, the Elder Council had to come to their senses? Or finally be voted out?

But it hadn’t happened yet…

And if Pia’s death, crushed under one of the boulders wasn’t enough…

Quiley put one paw in front of the other and walked herself away from the riverside, past tree after tree, through the thick underbrush of ferns and blackberry bracken, ignoring the ripe berries as much as she could. She didn’t want to admit that every time she saw a perfect one, she automatically looked over her shoulder to call back to Pia and brag about snatching it before her friend could.

But Pia wasn’t there, and somehow she’d already forgotten. It was like her mind couldn’t understand the idea that she had no friend to brag to about stealing the best blackberries.

Okay, so, they’d been friends. Sure. All the otters in the bevy were friends. Otters are friendly, okay? That didn’t mean anything. It didn’t mean that losing her was a big deal. Otters die. Everything dies.

Well, except dragonflies, if the legends were to be believed. But who believed those? Only kits and fools, like the Elder Council.

One paw in front of the other, feeling nothing but the soft loam under her paws, the leaves brushing against the fur of her back, and the light breeze in her whiskers promising September would soon be here, she kept walking.

If Pia had to die, why did it have to be right during the height of blackberry season? It was the injustice that bothered her more than anything else.

And really, most of all, she was mad at Pia for being so careless. For dying and leaving her to deal with all these other otters, who didn’t know her or understand her like Pia had, trying to console her over something that didn’t even make her sad. She wasn’t sad.

She wasn’t.

But All Encompassing Ocean, it was petty to blame Pia for her own death. Deep in her own heart, Quiley couldn’t deny to herself that she was mad at Pia for dying… but it made her feel small that she felt that way. Shouldn’t she be bigger than that? Shouldn’t the world have been better than to be a place without Pia? How could Pia have lasted for such a short time? She was supposed to live much longer, as long Quiley needed her as a berry picking partner at least. And then, maybe, a few extra seasons after that for good measure.

One paw in front of the other, Quiley’s webbed paws led her to the stagnant waters of the Emerald Swamp. Cattails bowed in the breeze, and dragonflies hovered eerily over the troublingly still water.

Water is meant to move, like otters.

Swamps are where water goes to die.

And dragonflies are the souls of the dead.

That’s what kits and fools believed.

But somehow, Quiley’s paws had led her here, to the dragonflies, looking for Pia. Because she couldn’t understand a world without her.

Far away from the other otters who had kept trying to comfort Quiley against her will, finally, tears streamed down the thick fur of her face, catching in her whiskers. She tried blinking them away with her inner eyelids, but the tears kept coming, blurring the already blurry view of the muddy, buzzy, horrid swamp.

But the dragonflies were pretty. The sunlight glinted off of their gossamer wings and jewel-cut eyes. Their long, thin carapaces were as brightly hued as shards of sapphire and polished turquoise. Quiley could almost believe they were souls incarnate, buzzing over the swamp grasses, whiling away their purgatory on this world before ascending to a realm of nothing but waterfalls that fell in loop-de-loops and somersaulting streams. An afterlife of water slides, where an otter could slide from one stream to the next, never stopping, never losing that rush, never holding still.

And stagnant.

Like this swamp.

Oh, Ocean All Encompassing, how could Pia’s soul be stuck here? She would hate it here. She’d smell the blackberry scent on the wind and insist on running and tumbling away from here, through the underbrush, ferns brushing her tawny fur, and a wide grin emblazoned across her cheerful face.

Her cheerful face.

Quiley would never see that grin again.

How had the others known how much Quiley depended on Pia when she hadn’t realized it for herself until her friend was already gone?

One of the dragonflies floated through the air toward Quiley, moving in sudden zigs and zags, singing with a droning buzz.

The otter cleared the tears from her eyes, wiping the wetness away with the back of her paw. “I suppose you’re Pia’s soul,” she said to the hovering gemstone of an insect. “Ready and waiting for me, just like all the otters back home would have expected.”

“And I suppose you’re the sun up in the sky, come down to cool off in the swamp water,” the dragonfly buzzed.

“What?” Quiley said, dumbfounded. She almost laughed at the sudden absurdity.

“I don’t know the rules of the game we’re playing,” the dragonfly buzzed, lowering itself to land on the bent-over tip of a long blade of grass.

“We’re not playing a game.” Quiley’s whiskers turned down in a frown.

“And I’m not someone’s soul.”

Quiley had known that. And yet, like a dumb kit in her first turning of the seasons, she’d walked right up to a dragonfly and called it a soul. “I’m sorry,” Quiley said, wiping at her eyes again. “I’ve lost someone… a friend. It’s left me a little loopy.”

The dragonfly bent its legs and fluttered its wings, but it didn’t take flight. Instead, it stood on the bent grass blade, watching Quiley through eyes that looked like blobs of raw turquoise. “Losing a friend is hard,” the dragonfly droned. “Many of the naiads I was friends with under the surface of the swamp didn’t survive long enough to molt into their adult forms.”

Quiley tilted her head, looking at the dragonfly much more closely. Suddenly, she imagined entire schools of baby dragonflies, living under the water, fleeing from schools of fish. She wondered what they looked like. Were they souls when they hatched? That would mean that naiads who’d been eaten by fish and hadn’t survived to fly above the surface wouldn’t be available for heartbroken otters who came here seeking solace.

No, it made much more sense that when a naiad molted into its adult form, taking on its wings and the gift of flight, that it was also gifted with the soul of a departed otter. Or other mammal presumably. If Quiley had been friends with a raccoon or a beaver, she’d want to believe that their souls would come here too.

Though, perhaps the raccoon or beaver would not want to believe that… Perhaps they had their own beliefs?

Quiley was not a theologian, nor a philosopher, but she was starting to feel like a very foolish young kit. Losing a friend can do that to you. Rip away the years of wisdom and experience you’ve gained, and leave you as small and sad as any child without metaphorical walls and emotional armor to guard them.

“When otters lose a friend, they comfort each other by saying that the friend’s soul has become a dragonfly,” Quiley said. She felt the dragonfly deserved an explanation for the large mammal’s intrusion into its life and swamp. Though, she pointedly didn’t tell it everything. It wouldn’t like the full legend.

“Fascinating!” the dragonfly exclaimed. “So, you hoped you could come here, talk to a dragonfly, and in essence, be getting your old friend back?”

“She wasn’t old,” Quiley mumbled. “She was much too young to die.”

“Do I seem like her?” the dragonfly asked, tilting its small head that was almost entirely composed of its strange eyes.

“No,” Quiley said. “Not at all.” There was so much bitterness in her voice that even the dragonfly heard it. Quiley could tell. Or else, maybe, she was just feeling so raw and vulnerable right now that she assumed her emotions were bleeding out of her eyes, ears, whiskers, and the tip of her tail. Every part of her was bleeding pain and complicated feelings like loss and regret over things that had never happened. Never would happen.

Pia would not have a litter of kits who the two of them would raise together, ignoring whichever useless male Pia had chosen as the father. The kits would not have unusually tawny, almost golden fur like Pia.

Those were silly dreams. Quiley had never even admitted to them. Never said them out loud. Never talked about them with Pia.

But she couldn’t deny the image in her head of golden kits, curled up between the two of them. She had daydreamed that image, and even if she never gave voice to those dreams, the image was there. In her head.

Quiley swallowed, gulping down the feelings and the pain. She knew what she had to do. It didn’t make any sense, but it was part of the legend. And as little sense as it made… She was starting to see the appeal.

“I’m sorry I don’t seem like your friend,” the dragonfly said. “I would have been willing to pretend for you, and we could have chatted. I’d like to help. See, you’ve already helped me. Dragonflies — we live most of our lives under water, dreaming about the few days we’ll spend flying. And my friends who died… they’ll never fly. I like the idea that their souls have gone somewhere, even if I don’t know where. And I think, I’d like to be friends with you.”

Quiley looked out over the swamp. The surface of the water dimpled where stalks of cattails and blades of tall grasses emerged from it. Dragonflies swooped low over the water, causing ripples where the fluttering of their wings disturbed the glassy mirror of sky.

Quiley had never eaten a dragonfly. She’d eaten other insects — crunchy and squishy between her teeth all at once. She preferred the soft sweetness of blackberries.

And it was strange that Pia’s soul would come to live inside this creature who had no idea of its own significance. It was nothing more than a vessel; a convenient shape for holding her essence until Quiley could realize how much she needed it.

“Yes,” Quiley said, “I think we can help each other.” She leaned close to the small creature, feeling her breath quiver through her whiskers and seeing it rustle the translucent wings.

Quiley leaned close as if she were going to tell the dragonfly a secret, perhaps confess her newfound friendship. The dragonfly held perfectly still. And Quiley’s teeth chomped fast.

The sapphire carapace crunched, and the turquoise eyes squished. The wings melted on Quiley’s tongue. But they weren’t sweet. Not the same kind of sweet as blackberries anyway.

When Quiley finished chewing, she sat up on her haunches, looked down her long belly, and sighed. Pia was gone. But also, Pia was part of her now.

Whenever Quiley hunted for blackberries, Pia would be hunting for them too. Whenever Quiley felt the blackberries’ sweet juices sliding down her throat, they’d be sliding down to join the essence of Pia, waiting in her belly.

And when Quiley died someday, they’d go to the afterlife of never-ending waterslides together.

Until then, it was time for Quiley to find a new home with a new bevy of otters. Pia had been pushing Quiley to leave for some time, and she’d been almost ready to agree. But then… The boulder. The numbness. Quiley didn’t think she’d be brave enough to voyage along the river, looking for a new bevy without Pia. Now she wouldn’t have to.

Quiley patted her belly in a sad yet satisfied way. Then she turned tail and left the swamp behind. It was no place for an otter, nor an otter’s soul.

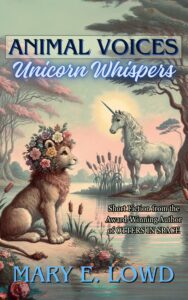

Read more stories from Animal Voices, Unicorn Whispers:

Read more stories from Animal Voices, Unicorn Whispers:

[Previous][Next]