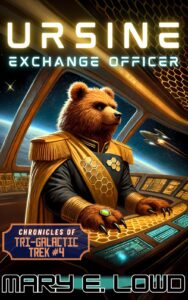

by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Ursine Exchange Officer, August 2025

Bear brains don’t zip and race from one idea to the next, constantly hurrying and bouncing around like shiny metal spheres in a pinball machine like cat brains do. And they’re not relentlessly, doggedly focused like canine minds, unwilling to let go of an idea like it’s a particularly enticing stick that needs to be chewed on once they get ahold of it. So, Grawf walked with Braklaw to her quarters in silence, simply focusing on the task ahead of her: dividing her zumble-bee hive and grafting a branch of her zinzinar shrub without damaging either precious being.

The grafting ceremony was simple — lighting a few candles that Grawf had made herself from zumble-bee wax taken from her own hive, consecrating the edge of the crescent blade of the traditional knife before slicing off a healthy branch of the zinzinar shrub, and then binding the branch to the roots from the arboretum with a carefully braided swatch of silk, soaked in zumble-bee honey. Grawf led the ceremony, and Braklaw played his part with the technical precision of someone who’d read a description of the ceremony and carefully memorized it.

The re-hiving ceremony was, of course, much more complicated, since it involved dancing with the zumble-bees between their established hive and the empty core of a hive awaiting a new queen.

Grawf lifted her arms and spun in slow circles, bowing and dipping herself as needed, while the worker bees flew in a friendly, buzzing storm around her, choosing their new queen and saying their goodbyes as the storm split in two, a smaller half of them eventually choosing to swarm around Braklaw. The other bear followed Grawf’s dance steps, but he was always half a step behind, clearly watching and copying her movements instead of dancing fluidly with the zumble-bees and looking at them, watching for the new queen to ascend, the way he should have been.

This was a bear who had never danced with zumble-bees before, and there was no way Braklaw could cover that, even if he had clearly spent the time while Grawf was waiting in the viewpoint lounge studying the ceremony as fast as he could.

Grawf was surprised, in the end, that any of her zumble-bees took pity on the imposter bear and chose to join his new hive. But then, she supposed, even zumble-bees may have ambition, and a new hive is a place where workers can rise suddenly through the ranks, taking on roles of more importance than they’d been allowed in a long-established hive. Or perhaps, more charitably, Grawf thought she simply had a collection of very kind, generous zumble-bees willing to take a chance on a bear who was trying very hard. Even if he was also failing horribly in his pretense.

“You are not who you say you are,” Grawf rumbled accusatorially when she’d finished putting the ceremonial objects away.

Braklaw was seated on the floor beside his newly founded hive, mesmerized by the zumble-bees droning lazily in the air around the fist-sized golden lattice that would soon expand into a much larger hive as its new inhabitants built outward from the core they’d been provided. He didn’t answer Grawf’s implied question. So, she left implication behind and asked:

“Who are you?”

“Don’t you know?” Braklaw asked with a sad smile. “Your friends apparently talk about me all the time, and the way that rabbit — she looked just like Sally Cottontail — looked right through me…” He shook his heavy head. “I’m sure she knew. Are you going to take the bees away?” He looked at Grawf with eyes filled with such sadness that it knocked all of the outrage out of her.

Grawf sat down on the floor beside Braklaw and his new hive. “No,” she said. “These zumble-bees picked you, whoever you are.”

“Teddy Bearclaw,” the other bear rumbled. “The great poet.” He shook his head again in bewilderment. He seemed so lost and small in that moment, in spite of his massive size, that he made Grawf think of a single zumble-bee, separated from her hive.

It made no sense that this bear in front of her could be a poet from ancient Earth who — in Galen’s words — died a long time ago. And yet, his demeanor — slouched, defeated, overwhelmed, and utterly out of place — supported his claim. Perhaps he was simply a very good actor? But then, why should he want to claim to be Teddy Bearclaw, and if he was lying, why hadn’t he tried to bask in the accolades that he’d walked into, without seemingly seeking them out?

Perhaps it was a claim of convenience — he had heard the others talking of this famous poet, and so he decided in that moment to take up the mantle of Teddy Bearclaw as a way to obfuscate a more deeply hidden, more nefarious identity.

No, Grawf didn’t believe it. She didn’t believe any of it. So, she would start by listening and see if that got her anywhere more solid. She asked, “If you are an uplifted bear poet from ancient Earth, then how did you come to be here in Xophidian space now?”

Braklaw — or perhaps Bearclaw? — shrugged his massive shoulders and said, “There was a… distortion? The air shimmered and looked wrong, inside a cave near the manor house where I lived. I walked through it, and it disappeared behind me. But so did the entrance to the cave. And when I found my way out through the changed passages there, I ran into several Xophidian miners. They assumed I was an Ursine who had crashed on their moon and taken shelter in their mine. I didn’t exactly feel like arguing with giant talking snakes with robot arms–”

Grawf could understand that. The Xophidians were rather uncanny.

“–so, I let them bring me to the station and call for help to get me ‘home.’ That was several weeks ago. Now I’m here. With you.”

There was an expression of such plain need on Braklaw’s face that Grawf had trouble doubting any of his words, ridiculous though they seemed. “Why didn’t you reveal yourself as soon as you met me, then?” Grawf asked. “Or in the viewpoint lounge when you heard my fellow officers discussing your poetry?”

Braklaw flinched like a bear with a bramble in his paw. “You heard them,” he said. “They think I’m a hero. A legend. The voice that whispers in their ears and keeps them company when they’re alone.” He shook his head fiercely. “I couldn’t do that to them.”

“Why not?” Grawf asked, her confusion written across her face. “They’d have been thrilled!”

“Or crushed,” Braklaw countered. “Those cats and dogs have worshipped me since they were kittens and puppies. What if I were tired or grumpy with them? What if I just looked at one of them the wrong way? They might carry that wound for the rest of their lives, and I wouldn’t know how to fix it.”

Grawf remembered how hard and stony Braklaw’s face had gotten when he’d heard Lt. LeGuin and Cmdr. Wilker talking together. It would be hard to see your hero look at you with that expression. As Braklaw said, it would be a wound that might never heal.

“Will you keep my secret?” Braklaw asked. “Will you help me become and stay T’di Braklaw and leave Teddy Bearclaw behind?” Several of his new zumble-bees had settled comfortingly on his rounded ears. The hive, at least, trusted him.

But the hive didn’t have an obligation to the uniform Grawf wore or the captain she answered to. This couldn’t be Grawf’s decision alone. She was only a worker bee on the hive that was the starship Initiative.

“I have to tell the captain,” Grawf said. “But I will tell him privately, and I will urge him to secrecy.”

“Who is the captain?” Braklaw asked uncertainly.

“A very reasonable sphynx cat,” Grawf answered.

Braklaw nodded and said, “Perhaps I had better come along. It might go better if I tell him myself.”

* * *

Grawf taught Braklaw how to lull his new zumble-bees to sleep in their hive with a combination of smoke and singing, and then she helped him to carry his sleeping hive and the pot with the grafted sprig of zinzinar shrub back to his own quarters. From there, they sought out the captain together.

Since the ship was docked and much of the crew was taking leave on the station, Captain Pierre Jacques had withdrawn to his own quarters for a little peace and quiet. The sphynx cat was reading an old book — an actual physical book, printed on yellowed paper — and listening to a Morphican re-interpretation of an Ursine opera when the two bears arrived at his door. With a deep sigh, he invited them in.

As soon as Grawf stepped into the captain’s quarters, her muzzle twisted with distaste at the sound of the insipidly precise music. She immediately recognized the opera — it was a classic on her world — but performed properly, it should have been full of passion, bursting at the seams with feelings. The Morphican vocals had stripped the song of all its meaning, leaving only a mathematically perfect but soulless rendition of the words and melody.

“I see you’re listening to the Warrior’s Blade,” Grawf commented as blandly as she could manage to the cat who was still sitting on a couch under a star-filled window with a book on his lap.

“Why, yes!” Capt. Jacques agreed. The pink-skinned sphynx cat (who had been glowering at his privacy being interrupted) brightened now, and his triangular ears straightened. He closed his book and put it aside. “This is a recording of a Morphican performance of the play that I was fortunate enough to attend a few years ago. I find it fascinating how two such different cultures can be brought together like this, giving an entirely new flavor to each of them!”

“Hmm,” Grawf rumbled, unsure of how to say anything more about this particular blending without offending the captain.

“I see you don’t approve,” Capt. Jacques meowed, seeing right through Grawf’s noncommittal response.

In spite of both her ears and tail being too small and rounded to skew, twitch, or wag in obvious tells of her emotions, sometimes these smaller mammals seemed to read the bear’s feelings perfectly anyway. Grawf wasn’t sure how they did that so easily, and she wasn’t sure she liked it.

“Too passionless?” Capt. Jacques asked, relentlessly pursuing the topic. Grawf simply nodded in acquiescence, hoping the topic would go away soon. The furless cat turned his attention toward the other bear standing in his quarters and asked, “How about you? What do you think of this Morphican performance of the Warrior’s Blade?”

Braklaw’s muzzle fell open, but no words came out. How could he comment on a specific performance of an opera he’d never heard before — one he should probably be familiar with — without giving himself away? But then, that was exactly what they were here to do. Give his identity away. Faced with the moment, though, Braklaw found he couldn’t do it. He didn’t want this irritable little cat to suddenly start adoring him. Or more likely, disbelieve him and force him to fight for the right to his own name.

“Actually, Captain,” Grawf said interceding, “our visitor here is very unlikely to have heard this opera before.”

“Oh?” The tip of the captain’s pink tail twitched with curiosity. “I would have thought most Ursines were familiar with this one. Isn’t it one of the most popular operas on your world?”

“My world, yes,” Grawf agreed. “But it turns out that our visitor is not an Ursine.”

The captain’s gray-green eyes narrowed. “Do go on,” the cat captain urged, unwilling to engage in any sort of guessing game with one of his officers. If Grawf had something to tell him, then the bear should come right out and say it.

Instead, the one bear looked at the other meaningfully, but Braklaw was still too frozen to speak. It had been one thing for him to tell another bear — one from another planet who seemed to know nothing about him at all — who he was. But telling an uplifted Earth cat who seemed to be very opinionated and interested in art and literature that he was Teddy Bearclaw? He just didn’t want to do that. It had been such a surprise for him to hear the rabbit, cat, and dog in the viewpoint lounge extolling the virtues of random lines he’d scrawled in his personal journals as if they were grand works of literature.

No, Braklaw couldn’t do it. He took a step backward, away from the cat captain and back toward the doors to the hall that had closed behind them. “Are you sure we have to do this?” Braklaw asked. “Does your captain really need to know?”

“Do what?” the sphynx cat asked, his tail upgrading from twitching to lashing as his curiosity morphed into impatience. “Do I need to know what?”

Grawf frowned. This wasn’t how she’d pictured this going. But when in doubt, the Ursine believed in choosing the most straightforward path. “Our visitor claims to have been thrown forward in time and space from ancient Earth.”

“Ancient Earth?” Capt. Jacques meowed inquisitively, more intrigued by the strangeness of this surprising answer than irritated by the dallying that had led to it. The cat got up from his seat on the couch and approached Braklaw, examining the bear more closely. “But there was only ever one uplifted bear on Earth.”

Looking cornered, the visiting bear bent forward, dipping his head in a bow that still left him towering over the sphynx cat captain, and said with as much quavering bravado as he could muster, “Teddy Bearclaw at your service.”

The sphynx cat walked a complete circle around the bowing bear, eying him from every angle, before announcing, “Fascinating. I don’t know whether this is some sort of ruse, but there are a lot of fans of Teddy Bearclaw’s work, and I don’t think any of them would take kindly to an imposter claiming his name. In fact, I count myself among them.”

The pink-skinned cat planted himself squarely in front of the brown-furred bear and stared up at him in a way that made their height difference feel like it had inverted. Braklaw felt very small indeed in front of this imperious cat.

Grawf cleared her throat and said, “Actually, Braklaw here is rather sensitive about that point. He doesn’t want anyone to know who he is. He didn’t even want you to know, but I felt it was my duty as your officer to inform you.”

One of the captain’s triangular ears skewed and uncertainty clouded his gray-green eyes. “Well, I suppose that does change things a little.” The cat tapped his paw against the comm-pin on the breast of his uniform and said, “Lt. Fact, could you please report to my quarters please? There’s something I’d like to ask you about.”

An even-toned voice answered from the comm-pin saying, “Yes, captain, I will be right there.”

Braklaw cast a panicked look at Grawf. He didn’t want anyone else brought into this. It was already enough of a mess as it was. However, the Ursine reassured him by saying, “Lt. Fact is an android — zhe looks like an arctic fox, but zhe’s actually a mechanical being. A sort of highly-realistic and intelligent robot.”

“Zhe?” Braklaw asked, feeling even more confused.

“Yes,” the cat captain said. “Fact is non-binary, so zhe doesn’t use either masculine or feminine pronouns. Also, zhe won’t share your secret with anyone if I order zir not to, and I trust zir completely. If zhe thinks your story is plausible, then we’ll move on from there.”

The cat and pair of bears stood together awkwardly for the few minutes it took Fact to arrive. As soon as the arctic fox stepped through the door of the captain’s quarters though, zir golden eyes widened in alarm. “Captain?” zhe asked. “You wanted to ask me about something?”

The sphynx cat gestured at the visiting bear and said, “This Ursine claims to be Teddy Bearclaw who died a long time ago.”

Fact grew very quiet. Much more quiet than an organic lifeform could be. There was a stillness to the way the arctic fox stood between the cat and pair of bears that made zir look almost like a statue, as if time itself had paused for zir.

“Well,” the captain persisted. “Isn’t that claim preposterous?”

As if jogged out of a glitch, Fact suddenly said, “Technically, it was never recorded that Teddy Bearclaw actually died. All we know from the records that survive from that time is that Breanna Schweitzer, the scientist who uplifted him, added a note at the beginning of one of his novels when it was published saying that she — and I quote — ‘missed him very much.'”

Braklaw staggered backward and pressed his paws against his breast as if he’d been shot through the heart.

“Posthumously published, you mean,” the captain argued.

The arctic fox android tilted zir head and said, “Perhaps. Although, the evidence in front of us would suggest otherwise. I have seen Teddy Bearclaw before, and this is him.”

Now all three of the organic lifeforms in the room — uplifted bear, Ursine, and irritated cat — stared at the arctic fox android in bewilderment.

“Explain,” the captain meowed in a tone that would brook no argument.

“Breanna misses me?” Braklaw asked, voice breaking. The big brown bear staggered his way over to the captain’s couch and took a seat there without asking. The couch was small for a bear, but this bear needed to sit down. “I knew I missed her… but… she was so long ago now… I hadn’t even thought about how it all seemed to them. Way back then. And the Cottontail family! Their children must all be grown… and dead…”

The big brown bear sank his head heavily into his paws and cradled it, shaking ever so slightly, trying to cover his discomfiture as best he could but not doing terribly well. He was a creature out of his own time, and for the first time, the full meaning of that was hitting him. And he was, quite reasonably, distraught.

It had been easier for Braklaw to pretend this far off future was entirely disconnected from the past he’d left behind when everyone around him was snakes with robot arms who’d never heard of Breanna Schweitzer. She’d been best friend, mother, and colleague to him. And now, she was long gone. He wished she could see the legacy she’d left behind. But more than that, he wished he could go home and tell her about it, as if it were nothing more than a story instead of a pressing reality that held him trapped.

“A few months ago,” Fact began zir explanation, “the timeline fractured, and I was forced to find my way into the distant past to repair the damage that had been done.”

“This was the mission where your head was found buried in that cave in England, isn’t it?” the captain asked. “And Galen, Consul Tor, and your beheaded body suddenly appeared on that Xophidian moon…” The pieces started coming together in the sphynx cat’s mind. “The bubble universe… with the alternate timeline… You met Teddy Bearclaw during all that?”

“Not exactly,” Fact corrected. “I saw him from a distance, but my vision is quite acute, and I can assure you with 98% certainty that this is him.”

“I thought that wormhole closed behind you,” Capt. Jacques meowed. “That’s what it said in your report.”

“I thought so as well,” Fact agreed. “But apparently there must have been after-ripples.”

“Ripples?” Grawf asked. “Like on a lake? Does that mean this wormhole might… um… flicker back into existence? And we could send our visitor home?”

Braklaw looked up with a touch of hope in his eyes, but Fact’s narrow vulpine muzzle tightened into a grim expression.

“I can run some calculations through a mathematical model,” Fact said, “but time-travel is… finicky. And last time, all three of us — Consul Tor, Galen, and myself — had super-imposed memories of two timelines, both the original, correct timeline and the altered, aberrant timeline. Whereas in this case…”

“You have always remembered that Breanna wrote at the beginning of one of my novels that she missed me,” Braklaw said bitterly.

“That is correct,” Fact confirmed.

“Might she have written that–” Braklaw stumbled over the words, because they were too heavy with hope, like boulders trying to pull him down to the bottom of a lake of delusions. “–after I died… much… much later… after returning… from here?”

Fact turned and walked up to one of the wall computers where zhe typed something with a rapidity that made his paws move like a blur. Then zhe said, “I have pulled up a full list of everything Teddy Bearclaw ever wrote. Please look at it and tell me if there are any titles here you don’t recognize.”

Braklaw had never thought about the lines of verse he scrawled and the stories he wrote down to amuse himself or the other, younger uplifted animals on Breanna Schweitzer’s estate as something that would end up as a list of titles in a bibliography for him someday. So, curiosity as well as hope pulled the bear toward the display on the wall computer.

Braklaw put a large paw up against the computer panel and traced his way down through the list of titles with a claw tip, gently gliding over the glassy surface. Some of them took a moment to recognize, because he hadn’t actually named everything he’d written. He hadn’t expected them to be published and remembered like this. But even so, every title was familiar. He had already written all of these books.

Turning away from the list with unshed tears sparkling in his eyes, Braklaw asked, “But couldn’t I just return to my own time and promise to never write another poem or story? That way my returning to the past wouldn’t change anything. It would be consistent with your records. Couldn’t that be what happens here? I mean, what already happened?”

“The wormhole had almost entirely disintegrated when Consul Tor, Galen, and my body passed through it. So, that is very unlikely,” Fact said with sympathy. “However, I will still run the calculations and see if there might be something I previously missed.”

The sphynx cat captain cleared his throat and said softly, “Fact, didn’t you already spend centuries as a disembodied head buried in a cave calculating the decay pattern of this wormhole?”

“Yes,” Fact agreed. “As I said, it’s unlikely that I missed anything. But I will try again nonetheless.”

The captain looked like he wanted to object to the idea of his most prized officer wasting time on trying to recalculate something that had already had centuries of uninterrupted thought devoted to it. However, the cat held his tongue on the subject and instead said, “In the meantime, it sounds like we should discuss Mr. Bearclaw’s options that involve staying in this century.”

“I would like to go to Grawf’s planet and live as an Ursine,” Braklaw said without hesitation.

“Are you sure?” the captain asked. “You would be quite sought after as a historical figure on Earth. You could teach, write, become a speaker. I’m sure any academic institution in Tri-Galactic Union colonized space would be more than happy to host you.”

“I don’t want to be sought after,” Braklaw rumbled, looking away from the others in the room and turning to look out the window behind him. He looked at the stars. Surely, the constellations here were different than he’d have seen back on Earth, but he’d never been good at recognizing constellations. So, basically, the star-spattered darkness looked the same to him. “I was living a quiet life, and I’d like to keep living a quiet life. Grawf introduced me to her hive of zumble-bees and took me through the ceremonies for splitting the hive, grafting a zinzinar shrub, and lulling the hive to sleep. I’d like to learn more Ursine ceremonies and spend more time around zumble-bees. I was the only bear on Earth. If I understand correctly, though, there’s an entire planet of bears out here. I think — if I can’t go home to Breanna — that’s where I belong.”

Grawf, Fact, and Capt. Jacques watched the sad, displaced bear stare into the darkness of a future he hadn’t asked to be thrown into. But he was here now.

“If you are to continue on to the Ursine homeworld,” Capt. Jacques meowed eventually, “then we should have Dr. Keller check you out before we get there. Surely, your biology will differ from standard Ursine biology, even if you look much the same from the outside. We’ll want to make sure the doctors on Ursa Minuet will be able to handle you and, also, that you won’t give yourself away the first time you go in for a checkup.”

Braklaw nodded. This seemed reasonable to him, even if he didn’t like the idea of another officer being brought in on his secret.

“Other than that,” the captain continued, “it sounds like you should spend the rest of your voyage with us studying Ursine culture. As far as I’m concerned, Grawf, this is your assignment for the next few weeks.”

“Yes, Captain,” Grawf said, and although she felt bad for Braklaw and what he was going through, the Ursine found herself excited about the chance to share her culture with an uninitiated bear who really wanted to learn about it.

* * *

Over the next week, Grawf spent hours every day with Braklaw, teaching him about every mundane detail she could think of from her culture. She told him stories about her childhood, practiced tending his zinzinar shrub and zumble-bees with him, showed him ceremonies associated with every part of the year, and took him to the ship’s lumo-bay to try out all of the lumo-programs she’d designed for herself. There were workout routines that helped Braklaw learn how to properly handle different Ursine weapons; meditation programs that helped both of them recenter themselves during this intensive cultural crash-course; and even a few purely recreational programs that simply gave Braklaw more of an idea of what to expect from the world he’d signed up for joining.

During it all, Braklaw practiced speaking Ursine with Grawf, instead of relying on her comm-pin for translations. If he was going to live among Ursines and fully integrate among them, he would need to know the dominant language. Fortunately, Fact was able to provide the bear with a jumpstart in the form of computer headset that fed the language straight into his brain while he slept. Of course, even with the knowledge floating around in his brain, there was simply no substitute for actual practice, so Braklaw stumbled his way through conversations with Grawf in a guttural, growly language far better suited to his vocal cords than the language he’d been raised to speak that had been developed by and for humans.

Grawf admired how hard Braklaw worked at this cultural immersion. And Braklaw felt overwhelmed, dizzy, and burned out by the constant, immense effort. However… he also felt like for the first time, he was learning about a culture that actually fit him. Even though Ursines had evolved on an entirely different planet in a distant star system, they had developed into creatures much more like him than the human who had uplifted him, and the world they’d created for themselves felt… designed for him.

Braklaw deeply missed Breanna Schweitzer, and he found himself poring over his old journal entries — which were apparently now taught in schools — looking for little tidbits of memories about her and the rest of their strange family that would help keep her alive in his mind. Grawf, on the other paw, specifically avoided reading any of Teddy Bearclaw’s novels, poems, or diaries, because she didn’t want them to interfere with how she saw Braklaw.

Braklaw had declared that he wanted to become a new person, an Ursine, and Grawf wanted to respect that. She saw how he had recoiled every time one of her fellow officers had complimented his writing — or even mentioned it at all — and she didn’t want to have that effect on him. She was the one person that he didn’t have to flinch away from, and she wouldn’t take that away from him.

By the time Braklaw’s appointment with Dr. Keller rolled around, the bear was beginning to make a passable Ursine. He strode through the halls of the Initiative beside Grawf, chatting away in Ursine as they walked to the med-bay. Other officers — mostly much smaller mammals — gave them curious glances, but this didn’t bother Grawf. In fact, it actually felt more natural to her than the way that the cats and dogs onboard generally treated her as if she were one of them, forgetting that there were profound differences.

Grawf loved the Tri-Galactic Union, and she was proud to serve on one of their vessels. But she was Ursine. Through and through, from her rounded ears to her heavy paws. Her heart beat to a different rhythm, stronger and slower, requiring her to meditate and hibernate, allowing her to interact with the universe at a different pace. She didn’t know if Braklaw would find he truly belonged on her world, living at that pace, but for now, she enjoyed his companionship and how it gave her a chance to revel in what made her own species’ ways special and worth celebrating.

The two bears entered the med-bay to find Dr. Keller — an Irish Setter with red fur, a long face, and even longer ears — tending to a sneezing Morphican sitting on one of the med-bay cots. The rabbit-like alien had been forced to remove his computer implants due to his intense bout of allergies and looked absolutely miserable without the mechanical suppression of emotions the devices usually provided.

“I’m sorry, Grawf,” Dr. Keller woofed, “I know that you and our visitor have an appointment right now, but we’ve been completely swamped by Morphicans with allergies this morning.” She waved a red-furred paw at the rest of the med-bay where several other similarly unhappy looking rabbit-aliens were being treated by various nurses. “So, the two of you will have to wait a minute.”

Turning back to the Morphican she was treating right now, the canine doctor said, “Until my team can figure out the cause of this rash of allergies, all I can do for you is treat the symptoms.” She handed the rabbit a small bottle of pills and said, “Take two of these every six hours. They should reduce the inflammation to where you can put your implants back in within an hour or so.”

“Thank you,” the Morphican said, taking the bottle of pills, clearly relieved by the news that he’d be able to resume using his implants soon.

“I wish I could do more,” Dr. Keller woofed with a sweetly sad smile as the Morphican hopped off the cot and headed for the med-bay door.

Once Dr. Keller was free, she turned her attention to the two bears and said, “The captain has briefed me on your situation.” Gesturing with her paw towards an inner office, she added, “So if you’ll follow me, we can take care of your checkup with a little more privacy.”

“I would have expected all doctor’s appointments to be handled with privacy…” Braklaw rumbled.

The red dog smiled brightly at the discomfited bear as they stepped into her office and said, “I suppose that would have been called for in your time. Please take a seat.” She gestured now at a pair of chairs on one side of a desk with a lot of computer panels on it. She took her own seat on the other side. “These days, most checkups are so perfunctory that there isn’t a need for a lot of privacy, and of course, if something requiring more discussion does come up, we can always step into my office or the surgical bay before discussing it.”

“Animals don’t get sick much anymore?” Braklaw asked, taking the seat he’d been offered.

Grawf sat down beside Braklaw and said, “That has actually been one of the significant advantages for my people of allying with the Tri-Galactic Union. The advances in medical care have been lifechanging for many Ursines.”

The Irish Setter doctor absolutely beamed in response to this praise of the state of her profession. “Like I said, we do what we can. Now, if you don’t mind, I’ll take a quick scan of you, Mr. Braklaw, and then we can discuss your options.”

“My options?” Braklaw hadn’t been expecting to have to make any sort of choices at this appointment. As far as he knew, he was healthy, and this was just a rubber stamp he had to get in order for the captain to leave him alone and let him go on his way.

Dr. Keller rose from her chair, holding out a uni-meter. “May I?” she asked, indicating that she’d like to scan Braklaw now.

Braklaw nodded and braced for some sort of disagreeable sensation, but the uni-meter merely made a pleasant chirping-beeping sound as the red dog waved it in the air around him.

“All done!” Dr. Keller barked brightly before sitting down again. “You’re in perfect physical condition. Now, as I was saying, I’ve been putting some thought over the last few days into your options. First of all, as I expected, you’re actually genetically and anatomically much more similar to myself and the other uplifted Earth animals on this ship than to Grawf here.”

“I look more like Grawf,” Braklaw objected.

“That’s all surface differences,” Dr. Keller woofed, “and we have the technology to change those differences, if you so desired.”

“Change them?” Braklaw’s voice had gotten very small for such a large bear. “What do you mean?”

“I mean,” Dr. Keller woofed insistently, “that with a few minor surgeries, I could make you look like a Newfoundland, St. Bernard, Mastiff, Leonberger, or Bernese Mountain Dog.” The Irish Setter counted these dog breeds off on her blunt claw tips as she listed them. “You’re too large to pass for much of anything else, and too barrel-chested to pass for a Great Dane. With a little medical intervention, you’d probably even be able to have children with an uplifted Earth dog, if you ever found yourself in that position. You could stay among uplifted Earth animals, without having to pretend to be an Ursine or revealing your true identity.”

Braklaw blinked. He’d spent the past week absorbing as much Ursine culture as he possible could, and here, this canine doctor was telling him that there was a way he could walk among his own people with the exact anonymity he craved and was currently denied by being a bear. The only bear who Breanna Schweitzer — or any of the scientists who’d followed her — had ever uplifted.

Braklaw shook his head, heavily but resolutely. “I can’t stop being a bear,” he rumbled. “I wouldn’t be who Breanna made me to be if I did.”

“Are you sure?” Dr. Keller pressed.

There was so much gentleness in the Irish Setter’s voice that it was hard for Braklaw to turn her down, but nevertheless, the brown bear shook his head again.

“Even if I didn’t stand out,” Braklaw said, “even if I weren’t recognized for who I am, I’d still be surrounded by animals who’ve read my most private thoughts. My fragmented, broken attempts at verse… and somehow… have come to worship them. Worship me. I don’t deserve that.”

The canine doctor looked like she wanted to defend the bear’s own poetry to him, but she managed to look away instead, embarrassed by the truth of what he’d said. Dr. Keller had read Teddy Bearclaw’s private diaries as a school-puppy herself. She hadn’t thought she’d needed his permission, because she hadn’t known he was — through a trick of time travel — still alive and someone who she would someday meet.

“It’s okay,” Braklaw said, almost as if he could read her thoughts. “You didn’t know.”

Dr. Keller cleared her throat, trying to cover how choked up those simple, gentle words from a literary titan had made her. “Well, then, I suppose you’ll be preferring one of your other options — the ones that assume you plan to live among Ursines. Shall I lay those out for you?” She rearranged the few portable computer pads and the uni-meter on her desk to give her something to do with her paws, something to keep her from looking at Braklaw — Teddy Bearclaw to her, even if that wasn’t who he wanted to be anymore — until she thought she could do so without tears brightening her soft brown eyes.

“Yes, please,” Grawf said, realizing that Braklaw and Dr. Keller needed her to mediate for them. “What are the other options?”

“Yes, well, you might actually be better suited to help choose between these two choices anyway,” Dr. Keller said, looking at Grawf. “First, we could do nothing. Leave Braklaw as he is, and as long as he stays healthy, that won’t be a problem. However, if he faces any significant health issues, he’d need to disclose his origins to any Ursine doctors and possibly return to a Tri-Galactic Union medical center for treatment. Most likely, an Ursine doctor would assume that he was an Earth dog who’d been altered to look like an Ursine — kind of a reverse version of the option he’s already turned down.”

Grawf nodded solemnly, considering this option. “As long as the peace holds between our people, I think that would be reasonably safe.”

“Is there a chance that peace won’t hold?” Braklaw asked, alarmed. He didn’t know very much about interstellar politics yet.

“There is always a chance,” Grawf rumbled. “My people are set in their ways, and our ways sometimes include war.”

Both Dr. Keller and Braklaw looked quite alarmed by Grawf’s statement, so she amended it, saying, “However, I do think it’s very, very unlikely.”

“What are my other choices?” Braklaw asked, trying to move this conversation forward. He wanted to go back to his zumble-bees and lessons on Ursine. He wanted to be done talking to this dog whose heart he could so easily break with a few misplaced words.

“I can give you a series of gene-therapy treatments that will re-mold your body at a cellular level, essentially turning you into an Ursine for all intents and purposes,” Dr. Keller woofed matter-of-factly, as if she hadn’t essentially just told Braklaw that doctors in this distant future could work magic.

“Is there any downside?” Braklaw asked in wonder.

“Well, yes,” the red dog admitted. “We can’t change your body at such a fundamental level without a cost. The treatments will take several weeks. They’ll leave you fatigued and probably in a fair amount of pain while you’re undergoing them, and of course, they’d be even more painful and fatiguing if you ever wanted to reverse the process. In fact, I really wouldn’t recommend it — this should be a one time thing. If there’s any chance that you’d change your mind later, I don’t recommend making this choice now.

Braklaw was alarmed by the seriousness of Dr. Keller’s tone. The red dog had suggested that she could change him into a whole list of different dog breeds with such an air of breeziness that it seemed strange to Braklaw that this should be so much harder. He already looked like an Ursine, and so, he would’ve thought that becoming one would be easier than becoming some sort of dog with floppy ears and a wagging tail. Apparently, his twenty-first century intuition couldn’t keep up with these far future times.

“Are there any real advantages to genuinely becoming an Ursine, instead of just passing for one?” Braklaw asked, hesitant to commit to a decision just yet.

“I imagine that you’d find hibernating easier,” Grawf suggested.

“Yes, you would,” Dr. Keller confirmed. “Hibernation is a physical necessity for Ursines, as we discovered when Grawf tried to skip her hibernation after coming aboard. As far as I can tell from looking at your scans, though–” The Irish Setter picked up one of the portable computer panels on her desk and scrolled through the information on it. “–yes, see, you’re really not very different from us dogs genetically. Based on what I know of history, your genotype — once Breanna Schweitzer worked it out — was most likely used as a blueprint for uplifting dogs. So, whatever urge pre-uplift Earth bears had toward hibernating, I think she must have played it down when designing you.”

Braklaw nodded. That did sound like something Breanna would have done.

“However, I also think that pre-uplift Earth bears simply don’t hibernate as fully as Ursines do,” Dr. Keller continued. “Technically, I believe they only enter a state of torpor during the winter, not true hibernation. At any rate, you may have a hard time concealing your inability to completely hibernate if you want to fully integrate into Ursine society.”

Braklaw looked at Grawf with a question in his eyes, and she answered it, saying, “Yes, that’s probably true. Our need to hibernate has made it harder for me to fully integrate into Tri-Galactic Union society, and the reverse would likely prove true as well.”

The Ursine shifted uncomfortably thinking about how much time she’d lost aboard the Initiative during her perfunctory hibernation. The mammals aboard the Initiative hadn’t meant to pressure Grawf into shortening her hibernation. In fact, the captain had been extremely supportive about her needs as soon as she’d expressed them. However, that was the difference — aboard the Initiative, hibernation was one of her needs. A difference to be accommodated. Whereas, among her own people, it was simply the way of life.

Time moved with a different gait among Ursines, and aboard the Initiative, Grawf was always aware that keeping to her people’s ways sometimes meant falling behind. She’d only hibernated for six months instead of the full year that was typical, and she’d still found that when she woke up, the Initiative had moved forward without her. That wouldn’t have happened on Ursa Minuet. And so, even with the best intentions, everything about Tri-Galactic Union culture was built in a way that pressured Grawf to keep her hibernations to a minimum, taking stimulants and avoiding the growing irritability and drowsiness as hibernation approached for as long as possible.

Grawf wouldn’t be surprised if in a matter of a few generations, the entire Ursine culture would find itself battling internally over whether to cling to their biological need for hibernation or find a way to overcome it entirely. Was it something that they would want to overcome? Hibernation was such a large portion of Ursine life… It was the downbeat that defined the meter of the rest of the rhythm of their lives. Without it, would they still be bears? Grawf wasn’t sure. But she knew that if she had struggled to make a place for hibernation in her life aboard the Initiative, then that crisis would be coming to the Ursine people as a whole soon. Ursine integration into the Tri-Galactic Union would demand it.

“If I’m exhausted and in pain from the treatments,” Braklaw asked, his voice still strangely small for a bear, “how will I keep up on my studies of Ursine culture? Will I have learned enough before we get to Ursa Minuet, if I can’t study anymore?”

Braklaw looked at Grawf with soulfully questioning eyes. She had a lot of sympathy for the Earth bear. He’d been through so much in the last few months, and he’d be going through a lot more, no matter what choice he made here.

“Braklaw,” Grawf said steadily, trying to help the Earth bear ground himself, “we’ve already worked out the backstory you’re going to use, remember? You were raised by a family of deeply religious dogs on a small, asteroid colony who found you in the wreckage of a crashed spaceship. Both of your biological parents died in the crash. You are an only child, and you led an extremely sheltered childhood, which explains why you don’t know more about either Tri-Galactic Union culture or Ursine culture. For this backstory, yes, you already know enough. If you want to undergo the treatments, then we can suspend our lessons for the remainder of the trip. You’ll be learning more than enough once we arrive at Ursa Minuet and you find yourself actually immersed in the culture.”

Braklaw nodded solemnly, seeming to weigh his possible futures out in his mind. All of his choices were strange.

“I would like the treatments,” Braklaw said.

Continue on to Part 3…

Read more from Ursine Exchange Officer:

Read more from Ursine Exchange Officer:

[Next]