by Mary E. Lowd

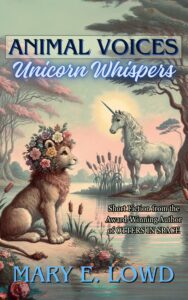

Originally published in Animal Voices, Unicorn Whispers, October 2024

When Arlene and Angelica married, they never expected to have children. Arlene was a river otter inventor; Angelica was a sea lion artist. And they were very happy together, sharing their lives and their passions, but theirs was the kind of union that bore fruit of the mind, not the kind of union that produced children.

Then Arlene’s business partner, a sea otter named Florentine, found an orphaned river otter child hiding out behind her inn, digging through the rubbish for scraps of food. The poor thing needed love and attention, a new home, and parents to care for him. He was so young, he only spoke a few words and couldn’t even swim yet. Angelica named him Elijah, and Arlene found herself unaccountably delighted to be raising a little fellow who looked just like she had at that age.

Arlene hadn’t realized — with how much time she spent surrounded by sea lions and sea otters — how much she missed the company of another river otter. She’d left her hometown along the side of the great river many, many moons before (back when she still lived under the name Arlow), and she’d never looked back. Yet, when she looked in Elijah’s little round, whiskered face, it was like she seeing all the way back to her own childhood, and she discovered an entirely new joy in life, beyond the joys of inventing and her love for Angelica: she loved being a mother.

Elijah was accepted by and played with the other children in the island village where Arlene and Angelica lived — a small, satellite village of the larger town on the mainland where Florentine kept her inn. Their village was a village of sea lions, and all the other children were sea lions. The sea lion children accepted Elijah as easily as the adults had accepted Arlene, perhaps more easily, since he wasn’t constantly pestering them with inventions they didn’t have any need for.

The sea lion village — Angelica’s hometown, and where she’d lived her whole life — was a small place, unchanged by the passing of time. The larger town where Florentine kept her inn, just a mile down the coast, had installed water wheels along the nearest river that powered street lights, cold boxes for keeping food fresh, and even heated water for luxurious bathing and more effective laundry. It was an exciting time to be an otter inventor, full of change and innovation.

Even so, Arlene chose to live in Angelica’s small town where the nights were lit and warmed by nothing more than bonfires and community connection. Sometimes, she felt strange, choosing a life that forewent so many of her own creations, as Arlene had indeed been responsible for many of the technological improvements to the larger town. However, she never truly regretted her choice — she worked with Florentine on her inventions, but her life and heart were with Angelica in the sea lion village.

Nonetheless, as much as Arlene had accepted that the village where she lived was entirely disinterested in her creations, she had no intention of raising her adopted child in ignorance of them. The sea lions of the village gave Arlene strange looks — even Angelica did — as she taught the little, wide-eyed river otter child about the loom she’d invented for stringing beads onto bracelets and necklaces. They tutted and tsked as young Elijah delighted over being able to create beadwork jewelry for himself by playing the keys on the loom like a piano.

Elijah made himself necklaces and bracelets far more easily than the other children his age who were still stringing them painstakingly by hand, the way it had always been done. His creations, of course, were clunky things — yes, functional, but the patterns and color combinations he chose were haphazard and aesthetically questionable. The choices of a small child, not a true artist. The adults were not impressed. Some of the younger sea lion children, though, were thrilled to play with Elijah’s pieces, dressing up in them and trading them amongst themselves.

As Elijah got a little older, Arlene started taking him for rides out to sea on her watercycle. With the child perched on her lap, Arlene could pedal the watercycle for hours, riding up and down the coastal waters, just beyond the reckless crashing of the surf. Arlene could let her mind wander, and Elijah watched the seagulls flying above, or the pattern of the trees and shrubs along the shore, or simply stared up at the clouds in the sky. It was a peaceful way to keep a tired child busy, letting them both get some rest. Sometimes, it made Alene feel like she was pretending to be a sea otter with the way they floated lazily on their backs, keeping their children on their bellies. As a river otter, she was less suited to that. She liked to feel the wind in her whiskers as her watercycle whisked its way down the coast. She wanted to be always moving, always going somewhere, always accomplishing something, even if watching a small, sleepy child who insisted they weren’t really tired sometimes meant that all she could really accomplish was keeping the child soothed.

It was a peaceful time, and Arlene grew to love it. Of course, like every phase of parenthood, it didn’t last, and soon, Elijah was too restless and wiggly to be kept busy in such a passive way. He wanted to stay back at the island and play with his sea lion friends, splashing about in the water around the island.

With both regret and relief, Arlene transitioned away from spending most of her days holding her new child, almost a dual creature with two separate bodies fused into one conjoined being, and back to working on her wacky ideas for inventions. She would scribble thoughts in a notebook while sitting back and watching Elijah play.

* * *

Then one day, some of Elijah’s friends — several sea lions close to his age — got into a competition with each other, trying to swim under an arch of rocks under the ocean, not far from the island’s shore. It was a common game among the children of the village. Angelica had played it during her own childhood. None of the village’s children, however, had ever been a river otter before, and river otters can’t hold their breath as long as sea lions. That’s simply a biological fact. Their lungs aren’t built for it.

But Elijah didn’t know that. And the little river otter child could be terribly competitive.

Elijah could swim now, but he didn’t practice very much. He preferred riding with Arlene on her watercycle, skimming along the surface of the water instead venturing underneath it. So, even though he made it down to the stone arch and halfway under it, Elijah got turned around in the depths. Suddenly, all the water looked the same, and the light from the sky was too diffused and dappled from being strained through the long, green ribbons of the neighboring kelp forest to help him find his way up. Elijah swam about in circles, lost and confused, until his little lungs gave out.

Elijah sank. River otters aren’t meant to sink, but the young otter sank. None of the sea lion children noticed, because they’d moved on to a game of chase through the green snakes of kelp, far too busy to notice one of their flock had gone missing.

Elijah surely would have died if Arlene hadn’t been watching the group of children play with half her attention. Even while working on her latest invention — a kind of mechanical arm for helping catch jellyfish — there was a sort of clock ticking down in her mind, keeping track of how long it had been since she’d last seen Elijah surface. And suddenly, Arlene dropped her work, feeling like it had been too long.

Arlene dived down, uncertain if she was panicking for no reason, being overly protective and foolish… then she saw her child floating far under the surface, limp and unmoving.

Arlene had never swum faster, nor felt like she was swimming slower, than as she powered her way through the water to save Elijah. The surface had never seemed farther away than when Arlene swept the drowning bundle of fur that was her child — and needed to stay her child, needed to stay alive — into her short arms and, clutching him tightly, turned to begin swimming back toward the surface.

With each stroke, the surface came closer, but it felt as far away as ever because even one stroke left was too far, if Elijah’s little body gave up trying. Until Arlene’s head burst through the surface and Elijah’s body began shaking, convulsing, coughing up water, she didn’t know… She didn’t know if she’d still have a child, or if that was going to be the moment her life branched horribly, irrevocably down a path she didn’t want to follow.

Both river otters were horribly shaken by the experience. Even though the uncertainty and terror had only lasted a few minutes, the effects of those minutes struck down to the cores of both of their hearts. Over the coming days, Arlene found they had both been altered, and not for the better.

Arlene already second-guessed her own parenting all the time and had to struggle to ignore the sidelong looks all the sea lions gave her for choosing to do strange things like ride around on a watercycle, but now those looks pierced right through the armor she’d built up against them. And Elijah — poor little soul — learned to be afraid of water. A terrible fear to have if you happen to be a river otter who lives beside the ocean with a bunch of sea lions.

For the next few weeks, Elijah kept his little webbed paws firmly on solid ground, no small feat given that he lived on an island and all his playmates were sea lions who did most of their playing in the water. Sure, Elijah would splash along the shoreline. He wasn’t afraid of getting his paws wet, but he had no intention of letting his head go fully under the water ever again.

At first, no one noticed, even though Arlene and Angelica watched their young ward closely. He was very good at making up excuses — “Oh, we need that special seashell I found earlier to use as a magic treasure in our game — I’ll just run and get it!” or “Nah, I want to pretend to be a sandworm and burrow through the sand. Don’t you like the way it feels all funny and grainy against your fur?” or even just a simple “Race you to the other side of the island! And no, it’s not cheating to run across the middle instead of swimming around — it’s just clever!”

Elijah was clever. In fact, he was so clever, he even managed to hide most of his fear of water from himself.

But Arlene loved that little river otter like she’d been given a chance to live two lives — one as herself and one as this wonderful little mirror of herself who made bizarre, wildly different choices from the ones she’d have ever made. And so, even if Elijah could hide his fear from himself, his friends, and even his doting sea lion mother, Arlene eventually saw through the facade.

* * *

“Why don’t we go swimming?” Arlene asked Elijah one day, leaving no room for the child to avoid the concept.

Except river otter children are slippery, wily little things, so Elijah smiled brightly and said, “Love to! As soon as I’m done making this bead necklace for Aurora.”

Aurora was one of the sea lion children, and she had genuinely been begging Elijah for one of his beaded necklaces.

“You can finish that later,” Arlene suggested, but the little otter shook his whiskered head firmly.

“I’ve been promising it to her for AGES, and I can’t put it off anymore.”

Arlene looked at the length of stringed beads. It was barely started, just a few blue and green beads in an erratic pattern. Still, Elijah made necklaces faster than any of the other children, since he used the mechanical loom Arlene had designed for that purpose, and she didn’t want to make him feel like she was pressuring him to swim. “I’ll wait,” Arlene said, settling down to watch with her full attention.

Arlene generally stayed fairly close to Elijah during the day, keeping one eye on him while keeping the other to her work. She would daydream inventions and tinker with blueprints while glancing up every now and then. But now, she kept her whole attention on Elijah. The two otters talked while the little one strung beads together using the loom. Elijah told his otter-mother all about an ongoing pretend game he’d been playing with some of the sea lion kids. All the while, he kept stringing on beads and then changing his mind about the colors he’d chosen, needing to unstring them — which invariably took twice as long as stringing them in the first place — and then redo the work from scratch with a different color of bead.

When the necklace was finally close to done, Elijah somehow managed to jam the loom, breaking it. Arlene had been watching closely, and she still missed exactly how it had been done. Of course, this meant the loom needed fixing before any swimming could possibly happen, as it was clearly an urgent disaster for one of Elijah’s favorite toys to be broken.

Elijah strung Arlene along like this for several days — never actually saying ‘no’ to swimming, but always coming up with ways to avoid it that seemed so natural for an easily distractible child that his mother couldn’t quite call the boy on it. If he’d still been a little younger, Arlene could have forced the matter more easily, but Elijah had grown into himself enough at this point that he had to be reasoned and reckoned with like a full person… even when he was being driven by a childish phobia no more mature than fearing the dark.

At night, after the young otter was curled up in his bed in his own small tent, Arlene and Angelica whispered together in their larger, neighboring tent, trying to work out how to handle him and his new fear. Angelica felt strongly that they shouldn’t push the boy, and they shouldn’t force him to admit to his fear, because that might just cement it further, making it become part of his identity instead of allowing it to dissipate naturally. She was convinced that if his fear were left alone, it would eventually melt away as easily as morning dew.

As a sea lion, Angelica didn’t see how a child could possibly do anything but grow out of such a troubling phase. Sea lions and otters are both built for the water.

But Arlene knew that an otter has more choice in the matter. For a sea lion to become a creature of the land, they’d have to severely limit themselves or else build clever contraptions like the mechanical legs she had once built for Angelica. (The sea lion had soundly rejected them, completely uninterested in trading her ease in the ocean for a gimmicky life on land.) Whereas, a river otter could easily forgo the ocean and even rivers, simply becoming like an oddly stout ferret or weasel with a preference for seafood.

Arlene feared that Elijah’s new phobia would lead to him growing up and moving far away, deep inland, away from any large source of water. It was a rational enough fear for an otter who had, herself, moved far away from the riverside colony where she’d been raised, choosing the wide ocean over a narrow river. She knew this situation was different, but she couldn’t shake the fear.

Children grow up and make their own choices, and sometimes they leave. It’s what they do. But Arlene wanted Elijah to grow up and find a life for himself somewhere nearby enough that they could stay close to each other. She never wanted to find herself picking between staying with her wife or following her child. She honestly wasn’t sure which choice she would make, and that was a strange discovery for an otter who had already built her whole world around the sea lion caves in order to stay with Angelica.

Arlene was happy with the sea lions. She wanted Elijah to have a chance of being happy among them too. The ocean was too big a part of their lives for the young otter to turn his back upon it now. There was too much left for him to explore.

Even so, Arlene knew that pushing the child might only make the situation worse — and would certainly upset Angelica — so she needed to take a different approach. The carrot instead of the stick. Or perhaps, in this situation, the chewy, deep sea jellyfish.

Arlene would bribe and lure her child back into swimming. That was her plan.

But she would take it one step at a time. The first step was to get Elijah back into the water at all. And even that required patience. So much patience that, as the days stretched into weeks, Arlene started to doubt herself, and the words she’d brushed off, so easily when said in others’ voices started to appear in her mind, spoken with her own internal voice. A voice she was accustomed to listening to and taking very seriously, because it was the voice that told her wonderful things like how to build a watercycle and power street lights and cold boxes with the energy from water wheels installed in the river.

But now the voice in her head betrayed her, and it started repeating the words of sea lions who had scornfully scolded, “You shouldn’t coddle that child with all those complicated contraptions.” She evolved their tired complaints, taking them further, all the way to accusations: “The watercycle is why Elijah won’t get in the water anymore. You spoiled him with machines as a toddler, and now he’ll never grow into a proper swimmer, never really belong in the ocean.”

Arlene found no defense even when she tried to imagine the words of those who actually liked her inventions — even Florentine, her business associate and biggest proponent would most likely respond to her situation by asking, “Why do you care so much about keeping Elijah on that island anyway? There’s plenty of world further inland.” Arlene hadn’t met any otters — or really anyone — who understood how she’d become a part of the sea lion village at all.

Arlene was an otter standing between two worlds, and her son was the only otter who stood there with her. She would have to figure this out on her own. So, she let the voices in her mind scream and complain and criticize, but she didn’t let them change her. She didn’t seek out help from people who she knew would just let her down. She relied on herself, put aside her inventions, and focused her entire attention on following Elijah around every day, waiting for the opportunities when she could gently cajole or lure him into the wavelets that lapped at the island’s shore. It made Arlene feel mad, losing the part of herself that worked on inventions, but she knew it was only temporary. Only until she got Elijah past this rough patch.

Sometimes, Arlene wanted to sit her son down on his rudder tail and just yell at him, force him to admit that he was afraid of the water, and then demand he get over it. But that would just drive a wall between them. So, she waited, softly cajoling, gently pushing, until she could reliably convince Elijah to splash around in the shallows with her again, simply enjoying the floating feel of the water lifting him off his paws, or maybe even buoying him up as he floated on his back — but never, ever rising higher than he could escape in two shakes of his rudder tail — before even trying to proceed to the next step of her plan.

The next step was controversial. Even Angelica was skeptical, and she mostly went along with Arlene’s plans. But sometimes, you have to make the right move for your child, even when no one else around you understands it. And Arlene was sure that she understood Elijah better than anyone else did. He was an otter surrounded by sea lions; she knew what that was like. She knew what it was like to be unusual — nearly unique even — until Elijah came along. And even now, she sometimes felt like no one would ever really understand her. Except maybe, someday, her son, if she parented him properly.

It’s a strange thing — parenting while being observed. You see yourself reflected in the eyes of others, and you know how it looks, but you can’t let it stop you from doing what’s right, even when it’s something that looks wrong.

And so, Arlene enacted the next step of her plan: she invited Elijah to come with her on a dive to gather deep sea jellyfish, far beneath the ocean’s surface, way out beyond the kelp forest.

* * *

As soon as Arlene began to introduce the idea, Elijah immediately looked stricken, his rounded ears twisting backwards and his long, elegant, white whiskers flattening tightly against his face. But then, Arlene explained the twist:

“Of course,” Arlene said, as casually as she could, “we will have to wear breathing masks, if we’re to dive down that deep.”

“B-b-breathing… masks?” Elijah asked, consternation wrinkling the fur of his brow between his bright eyes.

“It’s one of my inventions,” Arlene said. She knew that her son loved her inventions, and he would be intrigued.

“Do they… let you breathe the water?” Elijah’s ears had twisted back forward now. He looked excited. She was offering him a rope that would let him climb out of the hole of his phobia, and even if he wouldn’t admit to his crippling fear, he still recognized and desperately wanted a path away from it.

It doesn’t feel good to be afraid.

“Not exactly,” Arlene said. The little otter deflated at her words, but she rushed on. “But they do filter oxygen out of the water, so you can keep breathing air even while you’re under the surface.”

Now Elijah truly looked delighted. Arlene could see on his little face that he was imagining getting his webbed paws on a breathing mask and never taking it off, never having to fear the water again. This was exactly why the sea lions — who were already skeptical of Arlene’s inventions — would have disapproved of her offering one of them to her son as a crutch. It was a very real risk that he would never want to give it up.

But the sea lions already disapproved.

And Elijah already wouldn’t swim.

So, as much as Arlene felt the imaginary eyes of others judging her — and it caused her to judge herself too — she knew rationally that this step couldn’t actually make things any worse. And it might provide a path for Elijah to finally heal.

Arlene dug her breathing masks out of the wooden chest in the back of their family tent where she’d been storing them. She hadn’t used them for a while, but back when she’d first invented them, she’d had a marvelous time exploring the depths of the kelp forest with Angelica. This would be a very different kind of dive. Instead of a romantic adventure with her beloved, carefree and playful, it would be a stressful journey, constantly keeping an eye on Elijah, worrying about her young son. Because he wasn’t the only one afraid of him swimming. For all that Arlene had been pushing Elijah back towards the water, she still vividly remembered the limp feel of his small body in her arms as she swam desperately towards the surface, unsure if she would make it in time.

But she couldn’t show her fear.

Sometimes, it helps to share your fears with your children and show them adults can be frightened too. But sometimes… Sometimes there’s only room for the child’s feelings, and it’s your job as the parent to become a pillar of strength they can lean upon. Strong and blank. Nothing but supportive. And this was going to be one of those moments for Arlene and Elijah.

The breathing masks were rubbery where they fit over an otter’s face, fitted into place with leather straps and buckles that let Arlene cinch them up tightly around their heads, and then on either side of the face was a silvery canister. Elijah was delighted with how funny his otter mother looked wearing one, and as soon as his was fitted snugly on his face, he scampered, quick as can be, to the nearest tidepool hoping to catch a glimpse of his own face. His giggles at the sight of himself wearing the silly-looking thing came out as funny, gasping hiccups from underneath rubbery the mask, and Arlene found she couldn’t help but laugh too.

All suited-up, the only thing left to do was for Arlene to arm herself with a special net she’d designed for safely catching jellyfish. It looked a lot like a butterfly net. In fact, it probably would have worked perfectly well on butterflies too, but otters are a lot less interested in eating those. She strapped the long handle of the net onto an empty backpack she was wearing, ready to be filled with the delicious flesh of shimmery, translucent jellyfish before the day was done.

When Arlene and her son stepped into the lapping waves at the edge of the island, she was surprised to see Elijah rush past her, straight into the water. After weeks of avoiding the water, the little otter dove straight in, obviously eager to swim again. His fear had been holding him back, but he was an otter. He still loved the feel of the water all around him, buoying him up, tossing him about, and freeing him to do what comes most naturally to otters — swim.

Arlene’s heart swelled at the sight. She knew his love of swimming was still somewhere in there. All she had to do was give Elijah a chance to feel safe again, and he’d find his way back to how he was supposed to be. She followed him into the watery world of the ocean’s edge.

* * *

The two river otters — mother and son — swam past the rocky protrusions around the island and into the surrounding kelp forest. Arlene wished she could see Elijah’s face better behind his mask, because everything in his posture spoke of delight. She would have enjoyed seeing his smile, but alas, it was hidden.

Elijah swam jerkily with inefficient movements, more excited than skilled, as he wove his way between strands of kelp. But skill would come with practice. And furthermore, the skills he did have were rusty and mostly honed for swimming near the surface, not navigating the depths.

As the long green strands of kelp rose above them like knotted up tangles of ribbons, Elijah realized for the first time: this was the deepest he’d ever swum, and for a moment, panic shivered down his spine. But Arlene was keeping a close eye on her ward. The last thing she wanted was for this adventure to make Elijah’s fears worse, so she was staying very close beside him and caught hold of his small webbed paw at the first sign of his impending panic.

With gestures, Arlene indicated for Elijah to grab onto the straps of her backpack and ride along on her back. That way, the two otters were able to travel much faster through the kelp forest toward the deep crevasse where Arlene intended for them to do their hunting.

Arlene swam deeper and deeper, until everything around them was greenish-blue, dark and murky. The sun was too far away, buried beneath a thick layer of ocean, to help much here. Arlene still instinctively felt which direction led up and which way was down, but she wasn’t sure she could have explained how, given the diffuse, dim light and the way that the water pressed inward from all around. It would be very easy to get lost in the crevasse. But then, soft circles of light began to speckle the water in the distance.

Moon jellyfish.

Each jellyfish sported the outlines of four circles in the middle of its translucent bell that made Arlene think of the shape of four leaf clovers. Lucky. It was time to catch some of that luck.

Arlene pulled the net off of her backpack, and as she did so, Elijah let go of his grip on the backpacks straps. The young otter floated where he was while his mother twisted around and then held the net out to him. They held it together, and she helped him swoop it through the water, easily catching two moon jellies on their very first try.

Jellyfish aren’t exactly difficult prey. They don’t run away. They don’t seem to know they’re in danger at all. The one trick is that you want to avoid getting stung by their ribbon-like arms, so Arlene used a pair of tongs that she had stored in the backpack to safely pull the two moon jellies out of the net and stuff them in the backpack instead.

Once the net was empty, she handed it to Elijah to operate on his own, and then she followed him around, emptying the net whenever he caught a jellyfish or several. She couldn’t see the expression on her son’s muzzle, hidden beneath the mask, but his eyes sparkled with sheer delight. He was having the time of his life. And even better, he’d return home a hero.

Everyone in the village loved a good jellyfish feast, but mostly, they were a rare treat for brave, stubborn individuals who ventured into the crevasse just long enough to catch one or two for themself before needing to return to the surface for air. If more of the sea lions were willing to use Arlene’s breathing masks, that situation would change. But for now, a backpack crammed full with enough jellyfish to feed the whole village was going to get Elijah a lot of positive attention from all his friends.

Most of the jellyfish they caught were moon jellies, but they also found a patch of beautiful, orange sea nettles with long, trailing arms like ruffles. They even ran into a gigantic, gorgeous lion’s mane jellyfish that could probably have eaten them, if they’d been foolish enough to get themselves tangled up in its stinging tentacles. But in spite of Elijah’s enthusiastic interest in the giant pulsing blob with all its trailing strings and strands, Arlene insisted they keep a wide berth from that one.

By the time the backpack was stuffed so full of jellyfish that Arlene couldn’t possibly cram another one in, Elijah was swimming about much more smoothly, twisting and corkscrewing in the water like he’d never taken a months-long break from swimming at all. But the backpack was full, and filled as it was with jellies, it was heavy. The jellyfish looked lighter than air as they floated through the water, but balled up into a backpack, the weight of their rubbery flesh added up. So, Arlene put the backpack on again, affixed the net to it, and gestured for Elijah to start swimming skyward.

Anytime the young otter looked confused about which direction to take, he looked back at Arlene, and she pointed where she wanted him to go. Out of the crevasse, through the kelp forest. It wasn’t the most efficient way to travel, but there was absolutely no way that Arlene was leaving her son behind her, trusting him to follow her, as she swam on blithely ahead.

Elijah might look like his fears had been cured — at least so long as he was wearing a breathing mask — but Arlene was still deeply afraid of losing him to the water. She’d never been afraid of water before Elijah almost drowned. It was a strange thing to be afraid of something so prevalent, so all-surrounding. She’d always seen the water as a safe place, as long as she could remember, until it threatened to take her child away. Now… She wouldn’t turn her back on it.

Arlene wondered how long her own fears would outlive Elijah’s. Maybe that’s just part of being a parent, she thought. Carrying your children’s fears for them, so they don’t have to. If you’re older and stronger, you can take the weights off their backs that would crush them, and it’ll only hold you back a little.

A little isn’t too much, is it?

* * *

Arlene and Elijah emerged on from the ocean and walked straight to the central bonfires where sea lions were always cooking something. Giant cauldrons bubbled with fishy stew, and strings of fish hung above the fires, cooking in the heat and curing in the smoke.

Arlene handed the heavy backpack to her son, and Elijah’s narrow river otter chest puffed up with pride as he poured the gelatinous, rubbery, translucent contents out on a cooking mat. The jellyfish tumbled and sprawled over each other, tentacles tangling and bells squishing. Utterly delectable. Begging to be eaten.

Sea lions pulled their way closer, gathering around, until the otter boy was surrounded by cheering and clapping. He hadn’t just overcome his fear and swum deeper than he’d ever swum before, he’d returned to praise and applause for it.

Tired but satisfied, Arlene sat nearby and watched, while warming herself in the glow of the fire. The sky above darkened and stars came out, twinkling across the distance of space like deep sea jellyfish luminescing in the deep. Far and bright. Tantalizing.

Arlene didn’t take part in cooking the jellyfish. She’d done her work for the day. But she watched Angelica teach Elijah and some of the sea lion children how to prepare the glass-clear flesh in a variety of ways. Coated in spices and grilled; stewed along with other fish in a savory soup; and some of it was simply snacked upon — raw and slippery, chewy and salty-sweet in its freshness — while the rest of it was more laboriously prepared.

Arlene didn’t know how many trips to the jellyfish crevasse it might take before Elijah would lose his fear of the water entirely, but she knew they were on the right track. He would grow up braver for learning to face his fears, even if she’d had to trick him into coming at it sideways. Fears aren’t always best faced straight on. But he would overcome this one. Arlene was sure of it.

As she watched her son’s face, she basked in the reflected glow of his own pride in his accomplishment. She didn’t always know who she was anymore. Raising Elijah had become such a big, unexpected part of her life. Sometimes, it felt like he’d entirely eclipsed the person she’d been before he came along. The person she would have been without him — an otter inventor, completely focused on her work.

But even eclipses pass, and when they do, the world is a little more magical because they happened. Arlene wasn’t glad that Elijah had almost drowned, but she was glad of the way that helping him overcome it had brought them even closer together, forcing her to put aside her work and focus completely on him.

“Can we go hunting for jellyfish again tomorrow?” Elijah asked eagerly as Arlene tucked him into his bed of blankets and pillows in his tent that night.

“Not tomorrow,” Arlene answered, still tired from the long day and all the long days before it. “We still have jellyfish stew and steaks enough to last for several meals.”

“But when we run out?” Elijah pressed.

“Yes,” Arlene agreed, realizing that in spite of her tiredness, she was already looking forward to it. “When we run out, we can go hunting together again.”

Read more stories from Animal Voices, Unicorn Whispers:

Read more stories from Animal Voices, Unicorn Whispers:

[Previous][Next]