by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Kaleidotrope, January 2020

Sleek and silver, your spaceship sliced through the darkness of space. Cold, mechanical, everything a rocket needed to be to survive the harshness of vacuum and background radiation and simply the crushing depression of being totally isolated in the middle of a vast nothingness.

But inside.

Yes inside, a bubble of warmth and life support. Oxygen, nitrogen, puffy gases expanding out to fill the mechanical shell. All those good ingredients that let humans breathe. And dogs breathe. And cats breathe.

But the inhabitant of the spaceship had no dogs. (I know, it’s very sad.) They didn’t even have a few anti-social cats to stare at the walls with their ears turned backward, pretending to ignore their primate servants but actually hoping that one of them would come over and scritch that one always-itchy spot right under the chin.

No, no animals. No pets. It’s harsh out in space, as mentioned earlier. There isn’t room for extras.

A simple spaceship with a simple bridge — the Swiss army knife of rooms, a room that serves all purposes with a thin cot, a wall of control panels and little else.

But there is one touch of beauty. One glimmer of companionship. One green tangle of life.

A rose bush, planted in a raised pot, in the very middle of the bridge. On the shrubby green bush flowers blossomed in every color. A rainbow of colors. Delicate, quivering petals, protected from the harsh (it’s really harsh) space outside, keeping the bubble of life support beautiful, friendly, cozy. A home. Because when there’s something fragile but wonderful to tend to, something that needs you, something that you can watch grow and blossom… It’s easier to survive the darkness outside. The long stretches of silence, waiting for info-packets to arrive on the slow, slow, slow radio waves snaking their away across space. Because we haven’t found a way to drop down into hyperspace yet, where space folds and twists and braids, and you can pierce like a needle through one piece of the fabric and come out elsewhere instantly.

Black holes did not turn out to be magical space portals.

But flowers stayed beautiful.

No matter how far we travel, flowers are still beautiful.

And so we engineered one that’s necessary. One whose roots intertwine with the computer and life support systems of every spaceship, giving the humans onboard a reason to do what they want to do, what’s best for them, and what they would absolutely decide was unnecessary (though it is necessary, the most necessary) if they were ever given a chance.

So the rose was designed to be part of the spaceship.

And the person onboard must tend the rose, watching the flowers communicate the state of the engine — blue during take-off as the ship accelerates; yellow as springtime on Earth as the ship hurtles through space at full speed; and glorious, sensual, dusky red as the ship begins to decelerate, slowing down to arrive at the destination, an alien world so very, very far away. And a veritable rainbow of blossoms, every color — more colors than a box of crayons — when the ship arrives.

But there is no explanation in the manual for when the roses bloom purple and orange. Just purple and orange. That’s right, petals of rich, royal purple, streaked with the campfire glow of orange. Like an illness. A beautiful illness. Terrifying to behold.

Is the ship dying? You’re not sure. You’ve only flown on a rose ship once before, and the flowers only bloomed blue, yellow, red, and then finally rainbow when you arrived at your final destination. You check and check again, flipping through the manual frantically. The manual does not say what orange and purple mean. Or streaked at all. Or plain orange. Or plain purple. Your fingers twitch, wanting to grab the pruning shears. Perhaps, if you cut the blooms off, the next batch will grow in right: bright yellow. Safe yellow. A color in the manual. A color you understand. A color that means you will survive this mission and arrive at your destination alive.

But perhaps… pruning off the blooms this early will harm the plant? You’re not sure. You’re not a botanist. You’re just a plain old engineer of the mechanical variety, not rocket engines, more like bridges. Things that hold still. An architect, really. And you’re travelling to a new world to design buildings. And you really want to get there alive.

But the orange and purple streaks glare at you, recriminate you. You’ve done something wrong. Fed the flower the wrong amount of food? Kept the ship too warm or too cold? Or maybe it’s not your fault — maybe you’ve simply been horribly unlucky and flown through a patch of bad radiation. You’re already dying from cancer; you just don’t know it yet; those orange and purple streaks are a sign.

In a moment of panic, you clip each budding flower off of the bush. Crumple them in your hand, although they fight back with their thorns. Pierce your skin; cover themselves in your blood.

You blast the crushed, bloodied blossoms out the airlock.

And you refuse to look at the bush.

You watch the black screens, speckled with stars so far away.

Humans were never meant to be this deep in space alone.

But you’re not alone.

You can feel the rose bush behind you. Growing new blossoms, so slowly. You want to know if they’ll come in yellow. Or better yet red. Then the trip would be nearly over.

It’s hard to keep track of time in deep space. The computer can count. Count out the seconds and minutes. But seconds and minutes are meaningless out here. They’re meant to be fractions of days. Fractions of years. Rotations of a world beneath your feet. Rotations of that world around a sun.

No world.

No sun.

No time. At least, not in a meaningful way.

Sometimes, you look the numbers up — how many more numbers must pass until you arrive? But they don’t mean anything anymore. Hell, you had trouble keeping time zones straight when you had a planet under you, and those make a lot more sense than time at all in deep space.

Finally the rose’s new blooms open. (It was so hard not to pry them open with your fingers, force them to show their faces, what color they are, before they were ready to be seen.)

Pink.

You want to cry.

Pink isn’t in the manual either.

But maybe you’ve gone mad out here in space and forgotten what yellow looks like? Or red. Maybe your eyes aren’t working right.

Maybe those rose blossoms aren’t pink.

But they are. And you cry.

And you cry, and you rage, and you watch the clock on the computer, counting through those meaningless numbers. And finally you can’t take it anymore, and you rip the rose bush up from the pot, yanking on those thorn covered branches, tearing up the roots that trail down into the spaceship’s systems. You’ve lost your mind so thoroughly, you can hear the rose bush screaming at your sudden (but inevitable?) betrayal. No wait. That’s you screaming.

You throw the whole bush in the airlock, watch it blast into space, and then you sit on the bridge of your ship, cross-legged on the thin cot, staring at the empty pot of dirt. Wondering how many numbers will pass before you die.

But mechanically, you tend to the ship. You tend to yourself, still eating those flavorless packets of protein. (They hadn’t seemed so flavorless when you ate them beside a glorious rose bush, telling the plant stories of your childhood, as if a plant could listen or care.)

But now they’re tasteless. And you are alone. You were always alone. But you feel it bone deep now.

Months. Days. Years. Seconds. Numbers. Numbers. Numbers. When the autopilot begins the landing sequence, you’re sure you’re hallucinating.

The airlock opens, and you blink to see a mirror of yourself. You didn’t remember your hair being that color, or your legs being that long. No wait, this is another person.

Her eyes open wide at the sight of the empty pot, bits of dirt still un-swept on the floor around it. “Oh my god,” she says. “How did you survive?”

“I don’t know… I don’t know why the ship kept working.”

“What happened?” she asks, sympathy filling her voice like a symphony that you had dimly remembered from your childhood but never expected to hear again.

You try to stutter an answer. “The blossoms… orange and purple… not in the manual.” Your tongue is clumsy, unused to talking ever since you lost your rose. Killed your rose.

The other person comes up, offers her hand, and tentatively you take it. It’s the first thing you’ve touched that isn’t cold metal since the rose bush tore at your hands. The cuts on your hand are nothing more than white lines, barely visible scars now.

“I should have died. My ship… broke.”

She smiles sadly, looks around the single room you’ve been living in. “The roses aren’t really part of the ship. They’re just for morale. But before we added them, people kept going mad. And before we told people that they were essential, gengineered to be part of the engine, people kept ripping them out, hoping to cut corners, become more efficient. And then they’d go mad.”

She pulls you gently by the hand. “Come on,” she says. “You’re here. You made it. Come outside.”

And so you follow her off the ship, your bubble, and onto an alien world.

The flowers here are every color, and they glow with life under the radiant light of a triple sun.

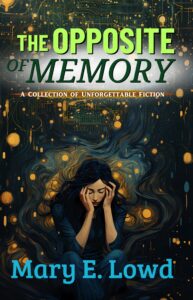

Read more stories from The Opposite of Memory:

[Previous] [Next]