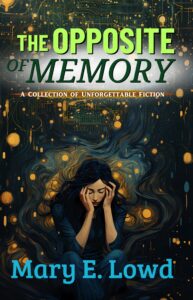

by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Analog Science Fiction and Fact, October 2014

A wise parent would never leave her one-handed child alone with a six-handed bachelor. A relationship between such unequals would only lead to heartbreak, or worse. Neither of Delundia’s parents, however, was especially wise. They’d met, married, and mated at the foolish young times after first-birth for Londe and second-birth for Arendell, soon leaving them with two young babies and only three hands between them.

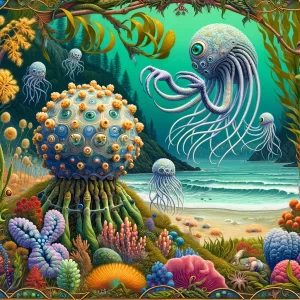

Arendell and his two hands kept the small family kelp-farm. Each day, Arendell himself tottled along the ocean floor on his nubby legs, watching his hands swim nimbly above him, among the healthy, growing strands of kelp. Like other hand-havers, Arendell’s body was round with six dark eyes on the upper half and six nubby legs on the lower half — perfect radial symmetry except for his mottled gray markings.

His hands looked similar, except their bodies were smaller and lighter with more primitive eyes; and their appendages were longer and more slender, covered in dexterous sucker disks. They pruned and harvested the kelp crop, swimming and climbing the ropy green fronds, as Arendell concentrated intently on controlling them from below.

Londe stayed at home, her one hand full with looking after the no-handed babies, Clenn and Delundia. Clenn was Londe’s birth-child; Delundia was Arendell’s. However, both children called Londe mother and Arendell father — titles that referred to their relative numbers of hands. Hand-havers are all sexed the same, but those with more hands are considered more masculine.

Until Londe’s third birthing time came and blessed Londe with an additional hand, her work was extremely challenging. Sometimes, Londe thought she would have gone insane, left alone all day with two babies, if it hadn’t been for Ebbence.

Ebbence was the town’s most prominent six-hander. He was homegrown and had never traveled. Yet, he was quite the scholar. Most importantly for his standing in the small community, he put his six hands to good use: he was building a watermill to catch the currents in the water they all breathed and convert those currents into useable energy. Very few of the hand-havers actually understood Ebbence’s work, but they’d all seen his preliminary results. He could light an entire house with his arcane contraption, and the light was steadier and brighter than from a well-fed spiny glo-fish!

Now, Ebbence wasn’t very social. He never showed much interest in other hand-havers. However, his estate shared a border with Arendell’s farm, and he could always count on being well cared for if he spent an afternoon in Londe’s house. Londe was a committed caregiver who looked after anyone in her house, without overburdening them with conversation of her own that might have disturbed Ebbence’s concentration. She kept house and listened, feeling infinitely grateful for adult conversation to listen to — even if she understood very little of it.

Thus, Ebbence spent a good deal of his free time around Delundia as a baby. He showed very little interest in her or her oppositely-parented sibling Clenn. They were nubbly, helpless, unhanded babies far beneath his notice. Ebbence was uninterested in children; they distracted from his all-important work.

Delundia, however, from her no-handed infancy was fascinated by Ebbence. He was always floating around the house after Londe with her and Clenn, seemingly handless like another baby. But, he wasn’t Londe’s or Arendell’s. She wasn’t sure whose baby Ebbence was.

One day, Delundia asked Londe, “Is Ebbence an orphan, Mommy?”

Londe’s hand halted, the bite of kelp mash hovering on its way to baby Delundia’s triple-mouth, located like a starfish’s at the nexus of her six legs, as Londe processed her surprise. “His parents died a long time ago, honey. Ebbence is an old man. Now why would you ask such a question?”

Londe reclined comfortably and her hand fed three more bites of kelp mash to Delundia, who waved her short, knobby arms in circles pondering. “Is he a cripple?”

This time the kelp mash went sailing and Londe’s hand went skittering after to scrape away the messy blob it left on the wall. “Goodness no!” Londe answered, getting herself and her hands (the other was feeding Clenn) under control. “What’s got into you?”

“Then why doesn’t he have any hands? How does he take care of himself if he doesn’t have hands, and his mommy died? Who feeds him?”

Londe convulsively retracted and extended her nubby legs in laughter. “The notions you get into your head! You’re going to be a troublemaker someday, ‘Lundia.” Control regained, Londe’s hands got back to the business of feeding. “His hands are at his own home, working on… what he works on. He has six of them.”

Wonder filled Delundia’s cluster of eyes. “So many…” she said.

“Yes,” Londe said, “As many as anyone can have. Though, he paid a steep price for that. Since all six of his birthing times produced hands, he’ll never birth a delightful baby like you.”

“How can he be so far away from them?” Delundia asked.

“He has better control than the rest of us. That’s all. He’s older and he can control his hands from farther away.”

Delundia kept quiet for the rest of the kelp mash, but then she said to Londe’s hand, who couldn’t possibly understand, “I’m gonna be like Ebbence some day.” The hand cuddled her dumbly and affectionately.

From that day on, Delundia showed a decided preference for Ebbence. She tottered around, swimming after him and listening to his ponderings and diatribes. But, unlike Londe, when she listened, she really listened. Londe hemmed and hawed and nodded, and Ebbence’s words passed right over her. She listened to pacify. Delundia listened to learn. No one knew about the change in her. She listened quietly and only talked about Ebbence’s inventions and her ideas to her mother’s hands.

Besides, there was another change in Delundia that was more obvious. She was nearing adolescence. Her body began to grow heavy with carrying the weight that would be her first hand. As she grew more uncomfortable, Delundia also grew bolder. She no longer had the patience to hold her tongue and found herself asking Ebbence questions when she didn’t understand him. Sometimes, she even made suggestions. He looked quite startled the first time, when she asked, “Have you tried curving the mill blades?”

It turned out Ebbence had tried it, but her question prompted nearly two hours of “discussion” — really more of a lecture — about what he’d found from the attempt. Different curves worked better than others. Some curves even slowed the mill down. Delundia was fascinated and delighted to have made a good, albeit already tried, suggestion.

Nonetheless, Ebbence remained unaware of her. He answered her questions and considered her suggestions, but he still spoke mostly to Londe. Delundia was infuriated by being treated like a child when she didn’t think of herself as one. Yet, there was nothing she could do to be seen as an adult — an intellectual equal — in Ebbence’s eyes as long as she was, technically, a no-handed baby.

Ebbence, as a bachelor who’d birthed all hands and no children, was understandably uncomfortable around babies. Their utter dependence was foreign and repugnant to him. And, the more Delundia listened to Ebbence, soaking up his every word and meaning, the more she grew dissatisfied with her pudgy, singular, baby body. She was embarrassed by the help she needed from her mother’s hand and claimed not to be hungry when Ebbence was around. Perhaps if she’d eaten more, her first birthing-time would have come quicker. As it was, Delundia’s body barely swelled at all from the unborn hand growing inside her. She was uncomfortable, but not visibly so.

Ebbence didn’t notice the change at all. One day, Delundia sat at the table, her reticent baby self, sullenly snubbing him because she felt snubbed by him — not that it made a difference to him. She was still an audience. The next day, when he asked after his little acolyte, Londe said, “‘Lundia’s recovering. You can come tell her about watermills tomorrow.” He didn’t think to ask what she was recovering from, so it was with complete surprise that he arrived the next day to find her double.

A dispassionate eye would have seen the scrawniness of Delundia’s days-old hand and the deflated flabbiness of her main-self body; the clumsiness of the hand and the exhaustion, total and all-consuming, of the main-self. But Ebbence, for perhaps the first time, was not dispassionate.

Maybe it was the total transformation — from subordinate baby to equal adult — a transformation he’d never observed before. Except in himself. Or maybe it was the strength of Delundia’s own self-image. Either way, Ebbence’s eyes saw something entirely different from the tired, slumped-and-bumbling, newly teenaged one-hander that Delundia’s mother saw.

Ebbence saw what Delundia hoped he would see, and he was bewitched.

Her chubby baby body had taken on a new aspect of self-possession. There was a look of concentration in her eyes as she struggled to control two bodies at once — the close, familiar one and the remote, new one. She felt a thrill controlling those distant, delicate motions, and Ebbence felt a thrill watching her. How agile her hand’s slender fingers were!

Ebbence didn’t say much that day. The shock was too great. Not to mention the distraction. However, when he returned on the morrow, Ebbence seemed to have returned to his normal self. No sooner had he settled at the kitchen table than he launched right into the details of his latest scientific experiments.

Except, there was a difference: when Delundia took advantage of one of his pensive pauses to make a suggestion, Ebbence sat forward in surprise, focusing each of his eyes on her. He even rotated his body, making sure the eyes from all around his torso examined what he hadn’t noticed before, something he could never have seen in a no-handed baby: another thinking, reasoning, intellectual creature.

When Ebbence finally fell, he fell hard, and the ensuing romance was swift though secret. It started simple. It started harmless. Delundia would tottle around Ebbence’s workshop with him all day, learning about watermills and electricity.

Having finally reached the self-sufficient age of one-hand, Delundia was now expected to be her own keeper, and it was such a relief to Londe to have one less dependent on her hands that she hardly noticed Delundia’s absences. When her parents did notice, Londe and Arendell were simply pleased that Delundia had chosen such a brilliant mentor.

Everyone expected Delundia to become the town’s next innovator. She was quick and clever, interested in every detail of Ebbence’s work. The two worked very closely together, and Delundia soaked up every piece of knowledge Ebbence had to offer her. She looked up to him wholly.

For his part, Ebbence had found a confidante in Delundia he’d never even sought before. She listened sympathetically as he poured out his soul, and when he finally steeled his courage to reach out to her as a lover Delundia did not reject him. Two of his hands twined long, skilled fingers with the fingers of Delundia’s one hand. Her hand returned their caress, and Delundia herself took his advances a step further. Boldly, her main body itself pressed against his, and Ebbence needed no more invitation. His four other hands all stopped at their work and came to her, delicately touching and delighting in every nuance of Delundia’s soft, young body.

In a seven handed dance, Ebbence and Delundia made love. Their main bodies pressed passionately, firmly together. It was an awakening for Ebbence, and he realized how deeply he hungered for what this beautiful, young creature had to offer. For Delundia, however, it was the beginning of an addiction.

Londe and Arendell had no objection when Delundia asked to move in with Ebbence. Both the dewy-eyed one-hander and the cagey old six-hander attested to the usefulness of their living together. For the sake of their work. And they did work.

Efficiency of the watermill went up sixteen percent. Delundia trained non-conductive coral to grow around and insulate several key lengths of wire in the town’s watermill, and she convinced Ebbence that they should start designing a miniaturized version of the watermill engines that could be used to power individual households.

Meanwhile, Ebbence was living in a hazy dream of sex and affection. Despite his age, he can perhaps be forgiven for neglecting to realize how quickly Delundia’s second birthing time was approaching. It had been so long since his own birthing times… Her parents, of course, assumed that with a genius like Ebbence to guide her, Delundia could do no wrong. Furthermore, they had thought Ebbence and Delundia were living together as mentor and apprentice — not husband and wife. So, they were as surprised as she was by the choice that was unwittingly made for her: Delundia’s second birthing was a baby.

In the fluster of confusion that followed, Londe and Arendell insisted that the two lovers marry. Ebbence was not opposed, and Delundia was far too exhausted and distraught by finding herself burdened with an unwanted baby to object.

The ceremony was small for Delundia had made no friends her own age, living so far from town and spending all her time with Ebbence. Perhaps if she’d spent her time gossiping with other one-handers instead of studying with Ebbence, she’d have been wiser when it came to her own body. As it was, Delundia had no idea that there was a connection between the passionate night-time activities she shared with her new husband and the infant who had stolen her visions of already being a two-hander away.

Delundia was disappointed. She’d been hoping for a second hand to help her on her work. Instead of finding her consciousness multiplied, she found herself crippled from working at all. Now, while Ebbence continued their work, Delundia’s one hand had to stay in the nursery that he quickly built for her and care for the baby whom they named Ata.

Delundia would not be daunted however, and she took to taking long walks around the surrounding hills, focusing all her efforts on developing the powerful control of her hand that Ebbence had over his. If she could not have multiple hands to control, she could at least learn masterful, long-distance control over her one hand.

Meanwhile, Ebbence found he’d fallen even deeper in love. Since all six of his births had been unfertilized hands, Ebbence had never had a child before, and he hadn’t expected how it would affect him. He took to spending his days in the nursery, cooing at the baby and growing increasingly irritable with Delundia’s carelessness.

“You lost hold of Ata twice today!” he scolded Delundia one evening when her main body came home. “If I hadn’t been here, the currents would have carried her right out the door!”

Exhausted from hours of exertion, Delundia broke into sobs. Her hand secured the sleeping Ata snuggly into a swaddling net as carefully as possible, and then drew against her main body. Clutching against herself and heaving with sobs, Delundia couldn’t understand how Ebbence managed to control his own hands from the other side of her father’s farm. It was so much easier to control herself when her hand and body were near each other…

Ebbence convinced Delundia to give up the endeavor and stay near her hand until their child was older. With five hands worth of skilled caresses (while his sixth hand watched the baby), Ebbence soothed his young wife, promising that she could rejoin him in their work later.

Ata was a cheerful baby, and Delundia couldn’t stay disappointed in her for long. She did wish for a second hand, but she didn’t complain. Londe never bemoaned having too few hands, and Ebbence, who was clearly delighted with Ata, never expressed regret that luck had dealt him a life with no children of his own. So, Delundia tried to be as stoic as them. As the time of Delundia’s third birthing approached, in fact, Delundia came to feel grateful for her experience of hardship. She was sure it had fortified her.

Nonetheless, she was more than ready for a second hand, and she delighted in her own awkward pudginess as her main body thickened. It was unusual for a one-hander to have birthed a baby, so she felt it was reasonable that she’d been disappointed. However, it was nearly unheard of for a one-hander to birth two babies, so she was sure this next birth would be the second hand she longed for. When the labor came, she hardly experienced the hours of excruciating pain. She was too focused on the expansion of her mind that would happen afterward.

So, it was with extreme confusion and a horrified wail that Delundia was presented with… another baby.

“How could this happen?!” she cried. “Why? Why?”

Londe clucked and tutted. “Now, now, your baby’s perfect. Nothing’s wrong.”

Arendell, however, understood, and was horrified to realize that his brilliant daughter who could harness the quasi-magical power of electricity was still ignorant of the most basic facts about hand-haver life. He wanted to whisper to her the secret that he had failed her by not passing on earlier: to birth hands, abstain; to birth babies, make love. But he looked at his cherished Delundia — a burdened young mother with two babies to her one hand. He hadn’t the resources to help her himself. She needed Ebbence. And Ebbence, who surely knew the truth of the difference between hands and babies, had not told his wife about it.

Had Ebbence made that choice for Delundia on purpose? Would Ebbence leave Delundia if she refused to have his children now? Arendell couldn’t be sure. He couldn’t think poorly of his old friend. Yet… He played it safe, and whispered to his daughter only the words, “Ebbence will care for you.”

And he did care for her. If anything, Ebbence grew sweeter and more solicitous. He devoted one hand to helping with the babies full-time, and Delundia, while disappointed in her lot, stayed as much in love with her wise, older lover as she ever had been. She never would have suspected that his love was the seed of her disaster… Until the day that Ebbence told her it himself.

Their first-born, Ata was a sprightly new one-hand, flitting about and enjoying her new duality. Watching her daughter made Delundia’s regrets all the more painful. While Ata had birthed her first hand, Delundia had birthed yet another baby and had begun to wonder if there was something wrong with her. Three births older than her daughter, Delundia had no more hands than her and felt deeply ashamed. Instead of being the capable two- or three-hander she had expected to be at this age, she found herself with only two births left, once again nursing two no-handed infants with her single hand.

“I hope Ata’s like you,” Delundia said, wishing for her daughter what she could never have for herself.

Ebbence rotated his body, looking at his wife with his full concentricity of eyes. “A scientist?” he asked.

“A six-hander,” she said.

“If she chooses that,” he said, puffing his stubby body, “I would be very proud.”

“Chooses?” Delundia asked.

“Of course,” Ebbence said. One of his hands — the one that helped in the nursery — came to his wife and caressed her affectionately. “I have been extremely gratified,” he said, “That your love for me is so great that you’ve never abstained from it, choosing to forego extra hands and stay a one-hander. It is an immensely flattering sacrifice.”

Delundia was furious now that she finally understood.

The screaming and shouting of their fight carried through the water all the way to Londe and Arendell’s house. Delundia’s parents were not surprised when she came to them, carrying one baby in her own hand and followed by Ata who’d been conscripted to carry the other.

“Ebbence is your husband,” Arendell said after Delundia made her case, begging them to let her stay with them. “The father of our grandchildren. And our oldest friend. He’s been your mentor and your caretaker. We couldn’t hurt him, ‘Lundia.”

“And how can you think of taking away Ata’s youth with your own selfishness!” Londe added, coddling her grandchild. “Ata will stay with us. But you have to go.”

Arendell and one of his hands helped his oldest birth-child carry her no-handed infants back to Ebbence’s estate. “Make up with Ebbence,” he begged as he left her. “I’m sure he’ll forgive you.”

Returned to her cage, Delundia swore that while she could not afford to leave Ebbence, she would never again love him. She banished his main body from the nursery and spent isolated days alone with the babies and the one hand Ebbence spent on helping her. It was utterly disheartening, but Delundia staked all her hopes on the day when her fifth birth would finally bring her a second hand of her own. That thought carried her, and, when her body finally started to thicken again, Delundia began to have a small glimmer of hope for her future. She’d never be the six-hander she’d dreamed of as a child… Or even a four-hander… But, she could yet be a three-hander like her father.

Then Ebbence came to her in the night.

Delundia awoke with her triad of hearts pounding. Her concentricity of mouths screamed, but Ebbence held her down with three hands. He begged her to see reason. He couldn’t think straight without her. This rift between them was affecting his work, and he needed to feel her love again. His fourth hand wrestled her own hand into ineffectuality, and his final two hands watched the babies. He pressed against her; merged with her; all the while murmuring his love for her and how he knew she couldn’t truly begrudge this liberty if she knew how much he needed her. It would be better for the both of them. Better for their work if he could concentrate. Better in the long run. When he left, Delundia sobbed until the morning.

Her fifth birth was a baby.

Ironically, for the first time, Delundia was not disappointed. For once, she’d known before the birth that it would, in fact, be a baby and not a hand. She knew, finally, that it wasn’t her poor luck to blame. It wasn’t the baby’s fault.

It was Ebbence. And what he’d done to her. Delundia felt as if her soul would burn out consuming her inside a chasm of grief and anger.

Isolated as she was, Delundia took an ironic comfort in her new child, Qyio. All the adults in her life — Ebbence, Arendell, Londe, and her two one-handed children — avoided Delundia. No one spoke to her. One of Ebbence’s hands watched the older infant, but Delundia kept Qyio for herself. At first, she meant to murder this infant, product of rape. The life she’d wanted was gone. The person she’d wanted to be… Eradicated. Stolen away, piece by piece, as her body had treacherously transformed unborn hands — her hands — into unwanted children.

Yet the only solace she found was in the cooing bundle of infancy that she cradled between her body and hand. Qyio was less hers than a hand would have been… But still hers. A spark lit Qyio’s infant body with a life both foreign and achingly familiar. The cerulean tinge of Qyio’s flesh was wholly Ebbence, but the pudgy curve around Qyio’s eyes was her.

To kill Qyio would be to darken the only light in her life. She might as well kill herself.

Instead, Delundia grew numb. Passing through her life as though she were only hands — dumb, mindless, with no sentient body in control.

In this state, Ebbence finally came to her.

“I miss my ‘Lundia,” he said.

She did not answer.

“Our work together has been so beautiful.”

Delundia’s body quaked. Perhaps she was laughing. Perhaps she was sobbing. She didn’t know.

“The miniaturized watermills we designed together power every house in the village.” Ebbence’s pudgy body gestured expansively with nubby limbs. “And our children…”

Delundia’s concentricity of eyes contorted to focus fiercely on Ebbence as she listened to what he had to say.

“Our children are the greatest part of all.”

More than anything in the world, Delundia would have wanted to go back to the beginning and save herself the mistakes that brought her to where she was… But she could not have that. She would never be the six-hander self that she could wistfully, heartbreakingly imagine.

Yet, she could be a mother who believed her children had been a worthwhile contribution. She could believe, if she tried hard enough… She could believe that she wanted the children.

Ebbence offered her that. And to the horror of the sliver of herself left over that still dreamed of all the great things a six-handed Delundia could have done, she gave herself to him.

Delundia chose love and submission. And passion.

Setting Qyio safely aside in a swaddling net, Delundia’s hand grasped Ebbence to her. The press of his body against hers, after so long, was electric. Before his hands could even leave their workshop to join them, the last fleeting hope of Delundia ever birthing another hand of her own passed away in a gasp of consummation. She would be one-handed forever.

At the venerable age of six-births, Delundia was a one-handed mother of five children. Despite her relative disability, Delundia never wanted for anything, materially. Her six-handed husband saw to that until the day he died — not long after their fifth and final child entered one-handed adolescence.

As Delundia resigned herself to her position in life, her other family members returned to her. Londe congratulated her on her wisdom and self-restraint: “What good does an extra hand do you,” she asked, “if you clearly don’t need one?” Londe scolded her husband for his short-sightedness. Why, they could have had another two or three children between them if they’d only worked harder and skimped more. Like Delundia. Instead, they were left in old age with all these useless hands rattling about.

Arendell stayed silent. He’d missed his chance to say his part when Delundia was young and a few instructive words from him could have made a difference.

For her part, Delundia saw to it that each of her own children were acquainted with all the facts, and she made it her personal mission to ensure that every one of them birthed at least three hands. They teased her for her hypocrisy — birthing only one hand herself and insisting they behave differently. But Delundia cajoled, pleaded, and reasoned.

Four of her five children folded easily. Ata put up the only real fight, having spent so many of her formative one-hand years being raised by Londe. In the end, however, Delundia won. Ata chose to appease her silly one-handed mother, and Delundia was delighted to see her daughter’s competence and consciousness expand upon birthing her third hand. It was a vicarious pleasure.

The greatest happiness Delundia ever knew, though, was when Qyio came to her near the end. While his siblings saw the silly one-hander that Delundia had chosen to be when life gave her no other choice, Qyio knew the broken-hearted six-hander that she kept buried deep inside. “I’ll continue your work,” he promised her, for Delundia had continued planning and designing, even without the hands to carry out her plans, to build her designs.

“I’ll string wires, coated in coral between every house in the village, creating a network of interconnected electronic signals…” He described to Delundia her own dream for the future of their village, a veritable technopticon of communication and convenience.

Delundia smiled with half of her mouths, thinking of the world she could have lived in if she’d only had the hands necessary to build it for herself. But then there would be no Qyio, and she couldn’t have that. He was so much like her, so much the person she’d wanted to be. She died loving her son and also regretting him.

Read more stories from The Opposite of Memory:

Read more stories from The Opposite of Memory:

[Previous] [Next]