by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Theme of Absence, January 2020

Amalioona prances into the stables, her tufted hooves gleaming. They are the same sparkling shade of white as a hillside of snow in the sun. They are dainty, perfect unicorn hooves. How is it, then, that she always seems to clumsily knock over the slop bucket — no matter where I put it — and kick up the fresh hay into a veritable dust storm?

Sneezing from the whirling dust, I try to sweep the golden hay back into a comfortable pile for her bed and mop up the dingy water from the bucket.

“Did she have a good time at the carnival?” I ask the trapeze artist who has walked my unicorn home. They do high wire tricks together — nothing stops a show like a unicorn on a unicycle on a trapeze.

“The best!” the trapeze artist exclaims before waving goodbye to Amalioona. Not to me. I’m just the unicorn’s keeper. Who would pay attention to me when there’s a shining, bright unicorn around?

I sigh and prepare Amalioona’s evening meal — a crystal bowl filled with lavender buds, rose petals, and four leaf clovers. Only the four leaf ones. Three-leafed clovers don’t taste right. She won’t eat them.

Amalioona lowers her head toward the crystal bowl and, like always, manages to scrape my shoulder and chin with the dagger-sharp tip of her clear-as-ice horn. I wear bandages constantly. Of course, the obvious solution is to put Amalioona’s flowery salad in a trough. Or even to secure the crystal bowl on a pedestal.

But Amalioona’s a hand-fed unicorn. I found her as a tiny fawn, small enough to tuck under my arm and carry home, wrapped in my baggy jacket with me. Now she stands as tall as I do, but she’s never outgrown the way I babied her as a foal. Why should she? If I try to lay down limits, she stops eating and her ethereal glow — silver like moonlight — fades to a sickly, flickering shade — gray like a staticky television screen.

And I’m to blame. And everyone around me steps in: “What’s wrong with her? Aren’t you feeding her right? Make her better! Make her better RIGHT NOW.”

And because there’d be nothing worse than being the person who killed the unicorn — the brilliant, beautiful unicorn who stars in the carnival and visits children’s birthday parties and volunteers at the library where disadvantaged kids practice reading to her — I always fold. Amalioona gets what she wants.

Amalioona snuffles out the last of the clovers from the crystal bowl, and then she snuffles my hand, gripping the bowl’s side. Her lips are warm and soft and being kissed by a unicorn feels like a blessing.

But then she prances off to her golden pile of hay, managing somehow to kick me in the knee with her perfect hoof on the way. The pain is sharp, but quickly dulls to an ache.

I watch her curl up in the hay. Her side heaves gently with her breathing. She closes her eyes and falls asleep. Her sleep radiates from her like the warmth of sunlight. You could almost feel rested just from watching her sleep. That would almost be enough.

I love her more than anything.

It is an honor to spend my days searching out four leaf clovers for her.

I limp a little as I make my way out of the stable, empty crystal bowl clutched in my hands, waiting to be filled again.

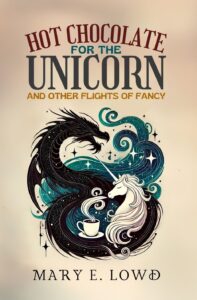

Read more from Hot Chocolate for the Unicorn and Other Flights of Fancy:

Read more from Hot Chocolate for the Unicorn and Other Flights of Fancy:

[previous][next]