by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Golden Visions Magazine, October 2010

Gerty had been snuffle-snorting about the melon patches all morning. She was looking for little people to play with, but all the bugs and mice seemed to be hiding today. Dormancy was in the air.

She tried asking a bird to play with her, but it was so high in the branches of the karillow tree that she had to shout at it. And the master scolded her for barking. The bird flew away anyway. They always did.

So, Gerty gave up her search and scratched out a comfortable spot under the karillow tree. She napped and dozed, keeping her ears tuned for the voice of the master. When he spoke, she woke.

“Damned converter!” he shouted, and Gerty knew he was working on the vehicle parked beside the house. She was proud; her master was handy.

“Does the sky know what I know?” he sang, and Gerty knew he had moved inside, his voice carrying through an open window as he washed the dishes. She was proud; her master’s voice was beautiful. She drowsed to sleep again.

“Lainey!” he cried, and Gerty woke again. She knew he was calling to his eight-year-old daughter; he was such a good family-man. Gerty was proud and began to close her eyes to go back to sleep.

“Lainey!” he cried again, “…Lainey?”

Gerty reopened her eyes. She picked her head up off the comfortable, dusty ground to listen better.

“Lainey??” There was strain in the master’s voice.

Gerty stood up and woofed, a soft woof her master wouldn’t hear. She started sniffing the air, her nose working overtime in search of the scent of Lainey. But, before Gerty could get too worried, a high, piping voice answered, “Here, Papa!”

Lainey came skipping along the road completely unaware of the great concern she’d caused Gerty.

“Come with me,” the master said, “we’ll check the melon patches.”

Gerty circled around the little girl several times, wagging her tail eagerly. She was glad the master’s daughter was all right, but to be sure — to be on the safe side — Gerty decided to accompany master and daughter on their excursion.

Besides, it was a lazy day.

“Clomp, clomp, clomp,” Lainey announced with each enthusiastic, stomping, footstep. Though, despite her ‘clomping,’ Lainey was actually stepping carefully, placing each foot delicately between the tender green melon vines. Whenever they came to a hub where the vines thickened around a round lump of melon, Lainey squatted down to get a look at it. Gerty, being a quadruped and shorter, already had the melons at nose height.

The two girls, biped and quadruped, sniffed at the melon while Master laid his hands on it, gently rocking the bulbous green-striped sphere, just enough to judge its ripeness — not too much, for that might rip its life-giving vines.

The master didn’t stop at every melon. Sampling a few here and there, as the troupe continued progressing around the curve of the lake, was enough to ensure the overall health of their melon patch.

Gerty, however, was a diligent servant, and she made it her job to sniff all the melons the master didn’t rock in his hands. Her nose was a more sensitive tool than the master’s hands anyway.

As they walked, the master told his daughter about ancient times, many, many years before, when the master was a mere boy. Neither Lainey nor Gerty could picture it.

Gerty had to miss parts of the story as she strayed farther and closer to the lake than the master, checking every melon. But, she tried to listen and catch what she could.

“My dad bought this farm when I was about your age, Lainey. It was already a melon farm, but a little run down. So, Dad had to renovate it.”

The melons all smelled so good. Gerty’s mouth watered as she checked them.

“We checked the vines, like we’re doing now. And we cleared the forest over there of vermin that came to eat our melons. Little rodents that would burrow into them, making homes as well of meals of the melons.”

Gerty wrinkled her nose. She didn’t smell vermin in any of these melons, but she could sure imagine them. The imagined smell made the fur on her neck bristle.

“There were bigger animals in the forest too. Gryphons used to nest in the trees. They slept in their nests, but during the day they’d run around the ground, like dogs hunting vermin.”

“They didn’t fly?” Lainey asked.

“Not much. I think the wings were mostly vestigial. They used them to glide down from their nests, but they climbed the trees to get back up.”

Lainey held her arms out and jumped up and down, pretending she was a gryphon. Gerty watched affectionately, before turning back to her important business. Checking melons. All the melons.

“It took a few years for Dad to clear all the vermin. I think they were pretty much gone by the time I was ten. I tried to keep a small one as a pet.” The master looked his daughter up and down. “I was about your age when I got that idea in my head. Mom was furious.”

“A gryphon would be a better pet,” Lainey said.

“Harder to catch,” the master said. “And harder to hide under my bed.”

They continued on for a while, neither father nor daughter speaking. They were to the far side of the lake when Lainey said, “I’ve never seen a gryphon in the forest.” She was looking over her shoulder at the thick green of the woods.

Gerty looked over at the woods too. She sniffed the air. There was no gryphon scent. As far as Gerty knew, there never had been.

“Of course not,” the master said, crouched down, still mostly paying attention to the melon cupped in his hands. The melon must have checked out okay, because he set it back and stood up. “What do you think they’d eat with the vermin gone?”

Lainey shrugged. “Melons?”

The master laughed. “Right,” he said and tousled Lainey’s hair. “Vegetarian gryphons. Good idea.”

Master and daughter continued on. Lainey kept asking about what the gryphons had been like, and the master told her what he remembered about them. Gerty, however, couldn’t keep listening. She was too worried by her latest find.

It was oblong-round and green with paler green stripes: it looked like a melon. But… She sniffed all around it. And, then, she sniffed all around it again. It did not smell like a melon.

There was no full, gonging sweetness. It lacked the tang of fresh green vine. Instead, it was musty with the slight sour of twigs soaking in the lake’s edge. There was something very wrong with this melon. Gerty wasn’t even sure it was a melon. It was… It was… Well, it was a doesn’t-smell-like-a-melon. And it was right here at the edge of the lake in the melon patch. With the other melons. The real melons.

Gerty ran back to the master and circled around his feet looking up at him, concern about the doesn’t-smell-like-a-melon deep in her eyes. The master offered her no reassurance. He merely stepped around Gerty and kept telling Lainey about water dragons. Apparently, gryphons had been essential to their life cycle.

Gerty had more pressing concerns. She ran back to the wolf in melon’s clothing. She took another sniff; then a hacking sneeze to get the sour smell out of her nostrils. A few plaintive whines leaked from her jowls. A quick look over her shoulder showed Gerty that the master still wasn’t paying attention. His words floated across the melon patch toward her, “Well, the last owners said there was one… But I never swam to the bottom of the lake to find out. And you’re not going to either.” After a pause, “Water dragons may not bother humans when they’re left alone, but I wouldn’t want to find out what a cranky one does if you wake it up at the bottom of its lair.”

Gerty huffed her frustration. She was having to shoulder this burden all on her own. She pawed at the doesn’t-smell-like-a-melon, and it rocked in its place among the watery vines. It wasn’t attached to the vines, she realized.

She afforded the master a few more hopeful whines, followed by one or two more urgent woofs. No response.

Lainey was crouched at the edge of the lake further along, trying to peer deep enough into the water to see a dragon curled up underneath. The master was telling her about how they only laid eggs every hundred years.

Gerty huffed. She’d have to deal with the doesn’t-smell-like-a-melon on her own. She pawed it again, scratching its surface with her claws. Its texture was harder than a melon’s. After another snuffle, she pawed the offending object, digging her claws in until she’d rolled it entirely out of its place, splashing a little in the shallow water.

Having rolled it over, Gerty could now see the doesn’t-smell-like-a-melon’s other side: a crack ran perpendicular to the pale green stripes. The fur on Gerty’s neck hackles started prickling, and she could feel her lip twitching into a snarl. Her snarl found full release and quickly turned into all out howling when the crack widened, growing and branching at either end.

The master came running. Lainey was right behind.

“What’s wrong girl?” the master asked.

Gerty had backed away from the doesn’t-smell-like-a-melon and was still bristling at it. The master looked down at the cracked, almost-melon-like object and said, “Well, I’ll be.” He squatted down and peered more closely. “Just look at what the lake’s washed up. I didn’t think I’d ever see one of these.”

The master’s presence emboldened Gerty and she edged her way closer to the cracking sphere again. She sniffed and huffed and quietly, nervously woofed. But she got her nose right up to it, and she could smell something inside. The smell was warm and pungent. Also, strangely pleasant and appealing. Gerty heard movement inside, and then she saw a blackened horn chipping away at the crack. Widening it.

“Can you tell what it is?” the master asked Lainey.

Lainey nodded, voraciously, her teeth biting her lower lip in anticipation.

“I halfway thought I was telling you myths,” the master said.

Gerty was becoming ever more fascinated as she watched the crack grow. The creature inside was getting closer to breaking out of its camouflaged egg. Already, the crack was large enough for Gerty to stick her nose in and get a real smell.

“Who’ll take care of it?” Lainey asked. She watched Gerty nose the tiny, sinewy creature with its bewhiskered, leonine head and golden scales. “If the gryphons always raised the baby…” She trailed off, not quite able to bring herself to say the word ‘dragon’ in the actual face of it.

Master and daughter watched their dog snuffle the tiny dragon, checking every length of its body. The two animals couldn’t have been shaped more differently — the one a straightforward quadruped with that most familiar of all animal shapes; the other bizarrely twisty, with little feet all along its curving body and tiny, angular wings sprouting from its back here and there.

Yet, it was also like watching a bereaved mother dog find an abandoned stray puppy. The dragon-baby had clearly already imprinted on Gerty, and Gerty would be facing fewer lazy days of fruitlessly asking bugs and birds to be her playmates.

“I wouldn’t worry about that,” the master said. “Shall we look and see if we can find any more?”

The rest of the circuit around the lake revealed six more eggs, all close to the edge of the water where they’d surfaced after floating up from the depths. Two of the eggs never hatched, but the other four produced wriggling, writhing, puppy-sized dragons just like the first. All of them imprinted on Gerty and followed her wherever she went.

In the days that came, Lainey and the master looked at the lake a little differently, knowing what was obscured beneath it. Lainey said, it made her feel like she lived at the end of a rainbow. “They’re like living gold! Just imagine what their mother must be like.” The master wasn’t sure he wanted to… Despite his assurances to Lainey that water dragons were perfectly safe, he couldn’t help but wonder. Gerty, however, was too absorbed in her new role, caring for and cavorting with the brood of five dragonlings, to worry about the giant they had come from. Or the giants they would one day become.

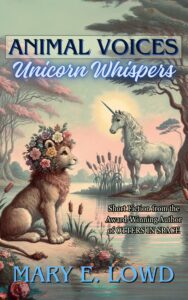

Read more stories from Animal Voices, Unicorn Whispers:

Read more stories from Animal Voices, Unicorn Whispers:

[Previous][Next]