by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in M-BRANE SF #30, February 2012

“You won’t regret this,” repeated in Bomani’s head over and over again as he made the distance from parked car to back alley door. The bulk of the bass speaker bounced with his pace, and he shifted its weight as he neared the coffee bar’s back entrance. Cradling the speaker between his chest and left arm, Bomani used his right arm to grab the door. He pulled hard, and the heavy gray-metal door swung far enough that he got his back to it before it slammed shut again. The door hit hard, square on his back, but this was his last trip, so Bomani didn’t mind.

“You won’t regret this,” continued echoing in Bomani’s head as he untangled the great length of black power cords and audio cables. Every minute or two, he looked over his shoulder expecting Kenny to be there. It was Kenny’s coffee bar, for heaven’s sake, shouldn’t he be there? What the hell. Bomani would thank him later.

The audio hookups had Bomani completely engrossed, his head bent over them in concentration, when his wife Minerva arrived. She placed her hand on the back of his neck. “I got your message to meet you here. I guess Kenny went for the offer.”

Bomani looked up, and a broad grin filled his face. “It’ll be the first live music Portland has seen in years.”

Minerva smiled, happy for her husband but worn out from a long day. She joined Bomani, sitting down on the floor. Her pleated business-skirt deserved better than a dusty, concrete floor, but Minerva was too tired to care. Her mind was filled with a different thought: what would Bomani’s gig do to their anniversary plans? One hundred and twenty isn’t the most important number, but they ought to celebrate somehow…

Minerva was steeling her nerve to mention the subject when Kenny emerged from the coffee bar’s kitchen, brushing off flour from his hands.

“You been back there all along?” Bomani asked.

“What, you think I’m gonna let some crazy, middle-aged, wannabe rock-star, work alone in my bar? Of course, I’m here.”

Bomani greeted Kenny with a handshake. “You are not gonna regret this,” he said. “Having a live band in here is the best thing you could do.”

“You’re an old friend, Bo, but let me tell you: I’m not worried about regretting this; I’m worried about going out of business. If the retro novelty of letting your band play here can rustle up a few more customers, you’ve got yourself a long-term location for your mid-life crisis. If not, I’m going to scrape up every silver dollar I’ve got and buy myself one of those Ent-Ind screens.”

“That would be a mistake.”

“Well, then, get your stuff together, and show me I don’t have to.” Kenny patted Bomani on the back and pointed him to his work.

Before Kenny could leave, Minerva rose from her seat on the floor and dusted off her skirt. “It’s been awhile,” she said. “Time to catch up?”

“Not really,” Kenny said, but he stayed and chatted nonetheless.

While Bomani configured the speakers, Minerva was filled in on everything there was to know about Kenny’s cat, Kenny’s motorcycle, and Kenny’s bar. He went on at length about the great location: right in the heart of oldtown-downtown, next to Powell’s City of Books, the historic district — where all those used CD stores used to be when they were all kids.

Bomani finished with the sound (Damon, another band member, was doing the stage tomorrow), and music poured out of the speakers. It was the Stones. Of course. Jagger wailing “Time Is On My Side.”

Kenny asked Minerva, “Does Bo still listen to that stuff? Twentieth century stuff?”

“The 1960s, specifically. And, yes, nothing else,” Minerva smiled.

“Doesn’t he get bored with it?”

“Nope. But I do.”

Walking out to the cars, Bomani offered to drive. “You look tired, baby,” he said. “I’ll drive you back to your car in the morning before work. Okay?”

“Thanks. That’s sweet.” Minerva got her bag out of her little, red hovercar and then came back to settle into Bomani’s plushy, older, hybrid SUV.

Bomani pulled the car out of the parking lot and aimed for the freeway. A few turns and a sparkling view of the city opened up around them. High above the Willamette river on an ancient four lane bridge, Bomani’s SUV was shooting like an arrow for home.

“I have thought about our anniversary, you know,” Bomani said. His eyes didn’t leave the road. “I know I’ll be playing at Kenny’s. So, we can’t travel. Europe, New Kokomo, and the moon base are out. But, it’ll be like when we met… Me playing on the stage. You, in the audience.” He looked over at her, took one hand off the wheel to squeeze her knee. “Won’t that be great?”

Minerva looked out the side window and smiled. “Sure. Sounds nice.”

Bomani could hear her lack of enthusiasm. “I know you wanted to go somewhere… ”

“Not really,” she said. “I just want it to be special.” She rested her head against the window and felt the reverberating bump of the road, a rhythm she missed in her hovercar. “Tonight, the idea of traveling makes me tired.”

Minerva must have fallen asleep before they reached home, because she woke up to the car pulling into the driveway. Bomani helped her out of the car, and she leaned against him walking in.

As they were getting into bed, Bomani said, “I didn’t want to wake you in the car, but I have an idea.”

In her tired state, wavy hair loose about her pajama-clad shoulders, Minerva simply looked confused.

“For making our anniversary more special,” Bomani clarified.

“Oh, right. What is it?”

His answer made her wish she hadn’t asked. “You know the memory drug I take?”

“It is too late for this.”

“And tomorrow will be too hurried. Give me one minute. Then you can think about it?” He touched her hair, put his hand under her chin, tilting her face until she was looking into his. She smiled.

“You know I can’t resist those eyes,” she said. “It’s like that Turtles song: a little bit of magic; just a touch of soul.”

“That’s the spirit. Now imagine this: we both take the drug. We talk to Damon and Christy, and they’ll help us out. Christy brings you to Kenny’s to see the band, and the two of them introduce us at intermission. Afterwards, we all have coffee together…” Bomani trailed off remembering the first night he and Minerva met. A big grin filled his face. “See?”

“Wait…” Minerva shook her head. “Wait, what are we forgetting with the drug?”

“Each other.”

“You want to forget each other? For our anniversary, you want to take a drug that will make us forget each other?” After a second, she added, “It’d be like missing your band. I want to see your big opening at Kenny’s.”

“It wouldn’t be like that,” he said. “You’d be right there.”

“But, I wouldn’t understand how important it was…” Minerva could care less about live music for its own sake at this point in her life, but she longed to see her husband fulfill his dream.

“You’d remember it all later. I could figure the doses so it would wear off the next day.” A dreamy grin filled Bomani’s face. “Just long enough for a second, magic first-night together.”

Minerva’s expression said, in no uncertain terms, “You’re crazy.” With her voice, she said, “You know I don’t like that drug.”

That was an argument they’d had before, so instead of fighting, Bomani just said, “Think about it.”

No more words passed on the subject that night, but Minerva found herself, the next day, doing exactly what Bomani asked. She kept thinking about it. As soon as she’d get the idea out of her mind, a co-worker would come by, and Minerva would plug Bomani’s band. She wanted a packed audience for him on Saturday… But the reminder would lead her thoughts right back to Bomani’s crazy memory-drug scheme.

So, Minerva gave in and considered the idea. She shut the door to her office and streamed a guilty pleasure over her computer speakers: Deryl Noia, her first album. The cool, strong voice filled her. Deryl Noia had the voice Minerva wished she had. How could Bomani want to forget this? When music touches you, why would you erase it?

No, Minerva would never understand that drug. When it came out, there were all kinds of horror stories. Addicts. Criminals who pushed the pills down their victims’ throats, forcing them to forget the crimes. She knew it had come a long way…

Doses were weaker now. All the health industries swore up and down, crossed their hearts, and the like that you couldn’t overdose on the over the counter version. The prescription stuff was stronger, but doctors didn’t hand it out easily.

Still, erasing part of your mind didn’t seem much like recreation to her.

And, suddenly, the album ended.

Damn, Minerva hadn’t heard a note of it since the first track. She’d been too busy thinking. So, she started it again. This time on loop. And, this time, she would really concentrate on the music.

Except, she couldn’t. Every time, by the middle of the second track, her mind started to wander. It wasn’t the fault of the music. She knew that. She’d loved Deryl Noia’s self-titled album since it first came out. She’d just heard it so many times… Her mind was used to it. And that was Bomani’s point.

That’s why he took those pills and forgot all his favorite music. Last week it was the Beatles’ Abbey Road. He popped a pill, and the whole thing was new again. He’d been in raptures, as always: how amazing the Beatles were, those guitars, that beat, how could anyone not love them?

Easy. Most people had heard each and every Beatles’ tune a million times. Not Bomani. He wouldn’t let that happen.

Minerva smiled to herself. It was the same enthusiasm that first ensnared her: he was a true musician. Even now, with Ent-Ind monopolizing the industry, Bomani wouldn’t sell out to them. Sure, in his day job, he was an Ent-Ind engineer. But, he wouldn’t take out a contract for his voice or guitar. They couldn’t touch his art.

On the way home, Minerva took a detour through the local pharmacy.

There it was. A colorful box labeled Mnerozia held the foil and plastic bubble packs with those familiar little pills. Minerva picked it up and imagined herself taking one. She must have stood there a long time, because a store clerk came over to check on her.

“Do you have any questions, Miss? Do you need help finding something?”

“Do you know anything about this?” Minerva held the Mnerozia out, and the clerk peered at the box to read the label.

“Sure. Are you trying to forget a trauma?”

“Actually…” Minerva wished she could go home and forget this. “It would be recreational.”

“We’ve got stuff a lot more fun than that.” The clerk laughed, but he saw Minerva’s lack of interest. “What did you have in mind?”

“My husband uses these to forget music. So, he can listen to it for the first time. Again.”

“Right. Well, I’d suggest cutting a pill in half for that. If you’re not going for a perma-forget, it doesn’t take much. That should be enough to make the music unfamiliar for awhile.”

“How does it work?” Minerva felt very small, asking these questions after watching her husband take the pills for years. Yet, somehow, the idea of taking it herself was very different.

“Mnerozia weakens connections in your brain and blocks the formation of new connections. So, say I want to see Terminator 5 again. I turn on the movie and pop a pill. While I’m watching the movie, I’ll start forgetting its connection to other events in my life. For instance, if I want to remember the first time I took a girl to a movie, I’ll be able to remember the girl, holding her hand during the movie, the whole bit — except, I won’t remember that the movie was Terminator 5.

“A few hours later, when the drug is out of my system, if I watch Terminator 5 again it will seem like a whole new movie. After watching it a couple more times, I’ll start to connect it back in to older memories — like that date.”

Minerva wondered how anyone could want to watch Terminator 5 that many times, but she let it pass. “So what if you are going for a… um… perma-forget.”

“That’s a lot harder.” The clerk handed Minerva back the box. “That whole box is a series designed to create a perma-forget.”

Suddenly Minerva held the box as though she thought it might bite her.

“Of course,” the clerk added, “it’s not like you just swallow every pill in the box and some part of your life is gone. If you were using the drug to forget a trauma — say a car accident — you’d take the first pill right after the accident, or as soon as you could after the accident. Then, whenever you found yourself dwelling on it… or if you woke up from a nightmare about it… you’d take another pill. By the time you worked through the box, the memory would be almost gone.”

“Almost?”

“Well, that’s what we call a perma-forget. I mean, you can’t ever really forget something that life keeps reminding you about. But, if you concentrate, you can forget it enough.”

“So, you can’t really overdose on it, then?”

“Nope. If you go home and swallow every pill in that box, you’ll have a hell of a time remembering anything that happens for the next day or so, but you won’t have any permanent effects.”

Minerva visibly relaxed.

“Yeah, that stuff’s pretty weak. I hear it was a lot stronger back in the twenty-hundreds.” His customer had clearly stopped listening, so the clerk asked, “Can I ring that up for you?”

“Sure,” she said. If she just opened the medicine cabinet at home, Minerva would find a whole stockpile of Mnerozia. However, she felt that buying the box herself would help steel her nerves for trying it.

At the cash register, though, Minvera decided to ask one last question. “So, okay, this is kind of weird, but my husband wants to do this thing for our anniversary where we, you know, use the pill to forget each other, and then our friends would introduce us again, for the first time…”

“Romantic,” the clerk said in a way that made Minerva feel certain he didn’t have a girlfriend.

“So, how many pills would you take for that?”

The clerk kind of frowned — he was thinking, but it worried Minerva. “That would be safe right?”

“Oh, yeah, I mean, you could take pills your whole life and never be able to forget your husband. Certainly not if you’re still married to him! But, I mean, even if you got divorced and then wanted to…” He could see he was losing his customer’s interest. “I’d take three of ’em. Then, you’ll need to find a way to focus on each other and your memories together while the drug’s in effect.”

“Like talking to each other? Flipping through photo albums?”

“I think something a little more intense…” The clerk looked embarrassed. “Maybe a little more… um… physical.”

“Right. I get the idea. How long would it last?”

The clerk shrugged. “If you stay away from each other it might last a week. If you spend any time together, you’ll probably start remembering in less than a day.”

“Perfect,” Minerva thought. “Thanks.” Then she went home to try it.

Back at Groundswell Coffee, Bomani was helping Damon power-screw the bolts into place on their stage. The two of them were working each other into frenzied daydreams of the deafening applause and uproarious cries of “encore!” their band would face come Saturday night. Then, Bomani’s phone rang.

“Would you turn that down?” he yelled to Damon over the booming “Louie, Louie,” as he answered his phone. “Minnie?” He walked to the far corner to get some quiet and privacy. He knew it was her from the jazzy ring he’d assigned her number, but all he could hear on the other end was crying. “What’s wrong, baby?”

The hiccoughing pulled itself together. “I’ve lost an album… They only did fifteen. And I lost one!”

“Well…um…I’m sure it’s still on your hard drive. I’ll run a search. Or, we’ll buy the files again. What album is it?”

“You don’t get it! I hate it now!”

“Then why do you care if you lost it?” A slow wail started on the other end of the phone. “Hold still, baby, hold still. I’ll fix this for you, Minnie. Tell me what happened?”

With a little more coaxing, Minerva pulled herself together. “I thought, if I was going to try it — the Mnerozia — I’d like to feel like there was a new Clashing Greens album again. There hasn’t been one in so long…”

“That makes sense.” Bomani remembered how excited she was whenever a Clashing Greens album used to come out. “Wait… You took it? You took the pill? Why didn’t you wait for me? I’d have been there to take care of you through it…” He knew how much Mnerozia scared her.

“I wanted to do it alone. I wanted to make sure that I was up to it. If we take it to forget each other, I won’t have you to walk me through it.” She started sniffling again. “Oh, Bomani.”

He wanted to hug her. Poor girl. Stupid cell phone. “So, you took the pill, and you listened to a Clashing Greens album. You know that you have to listen to the album a second time, right? You won’t remember it without re-listening to it.”

“But I hate it now! The lyrics are so stupid.”

Bomani thought about that. “Was it the reunion album? Their last album? Swansong II?”

“Yes.” Her voice was small.

He pictured the night Swansong II came out. They sat on their bed, listening to it in the dark. Minerva insisted on listening straight through. She hadn’t said a word. And, when it was over, her face was stiff. She wouldn’t talk about it, except to say, “Let’s listen to it again.” By the end of the week, she sang along with every song, listening to it while they cooked. He’d hardly been able to play a song of his music for months.

“Honey,” he said. “You hated that album the first time you heard it. That’s why you hate it now.”

Minerva was silent.

“I know it was a long time ago, a really long time ago, but think carefully. Try to remember. I know you wanted to love it… But, it took time to grow on you.”

Minerva stayed silent.

“You should listen to it again. You’ll like it better each time. I promise. Do you want me to come home?”

There was a pause, and, then, “Keep working on the stage with Damon. I’ll be okay. What would I do without you?” Bomani grinned, but Minerva couldn’t see it over their cheap old-fashioned phones.

When he got home she looked fine, but he gave her the hug that had been waiting inside him anyway. “You doin’ better?” he asked.

She stepped back, keeping her hands in his, and looked at him. As she started to speak, he put his finger to her lips.

“Wait,” he said. “I know that you’re worried by what happened with the Clashing Greens album. But that can’t happen with us. I was awestruck the first time I saw you. My heart was yours. Love at first sight, right?”

She lowered her eyes, letting her thick hair obscure her face, but she did smile. “I don’t look like that anymore.”

A bright white grin: “Close enough.” He traced his fingers under her angular jaw line. “You look damn good for a woman over a hundred.”

“I stopped counting at fifty.”

“Yeah, most of our generation did. But, you’re dodging the question.”

Minerva moved back against Bomani’s strong chest and nestled her head into his shoulder. She remembered that night: watching him on stage, being introduced by a friend, feeling so shy, and finding him so friendly — like he was now. “You’re right. It was love at first sight. We’re very lucky.”

Bomani covered the back of her head with his broad, brown hand, pressing down the wavy hair. “That’s why it’ll be okay for us.” They stood there, rocking in each other’s arms, for a while. Talking about the band and the big night. Then, they naturally disentangled and moved towards the bedroom to begin getting ready for bed.

Minerva was still brushing her teeth in the bathroom when she said, around the toothbrush, “You were playing ‘Louie, Louie’ when I called. I heard it in the background.”

Bomani came to stand in the door, leaning against the doorframe. “Yeah, that’s right.”

“You know what you always say about ‘Louie, Louie’?” Minerva rinsed her toothbrush out, and nanite toothpaste swirled down the drain.

“There’s no point in forgetting it,” Bomani answered. “It sounds like you’ve heard it a million times before you’re halfway through.”

She put her toothbrush away. “That’s its charm.”

“Right.”

Standing there, in her pink negligee, Minerva looked him straight in the eye. “Maybe we’re like that, and it won’t do any good.”

Bomani laughed. “Then it won’t do any harm either. It’ll be like we never took it.”

“That’d be nice.”

In all seriousness, Bomani said, “I think it’d be nice if it worked.” He came forward and took her hand, then he drew her backwards into the bedroom. Sitting on the bed beside her, he said, “Remember how exciting it was? Meeting each other for the first time? I couldn’t believe how lucky I was, how beautiful you were, and how much you seemed to like me. The way we hit it off was the highlight of my life.”

Minerva thought about it for a time. The drug scared her, but Bomani wanted it so much. He wouldn’t push her like this if he didn’t. She looked in his eyes and realized it would break her heart to say ‘no’ to him. He was such a puppy. “All right, we’ll give it a try.”

Again, that bright white grin. “Next year, we’ll do whatever you want for our anniversary.”

As Minerva turned out the lights, she said, “We’d better.” Lying in the dark, Minerva was simply thankful she had two more days to get used to the idea. Would that be enough time to make her ready? It would have to do. She fell asleep running over the plans in her mind for the next two days. Even if she wouldn’t be ready, she could make sure everything else would be.

And so, the night before the big day, Minerva and Bomani each swallowed three pills with a flute full of champagne. Then, they retired to their bedroom and got about the business of forgetting each other. Minerva knew that the tighter she clung to her husband, the more fully the Mnerozia would work its way into her memories and erase him. Yet, in her fear to lose him, she clung to him tighter than ever.

In a warm haze, Bomani rose from their bed, dressed, and left for Damon and Christy’s where he would spend the night. The drug was already working, and he couldn’t remember why he had to leave for Damon’s in the middle of the night. Except, he knew the big gig was tomorrow, and if he slept on Damon’s couch, he’d be there to help out in the morning.

Puzzled, Minerva watched him go. Her confusion didn’t last long. She was asleep in mere minutes.

Christy called in the morning to remind Minerva they had plans together that night. Something at Kenny’s coffee shop. She’d come over around three, so they could get ready for it. Pick out dresses. That kind of thing. Minerva agreed and, at Christy’s suggestion, spent the intervening time working in her garden. It was a good suggestion — the house felt strange today. The garden, however, was the same as always.

While Minerva spent the morning feeling oddly empty, Bomani didn’t miss her at all. Damon and Bomani hung out at Groundswell Coffee all afternoon. They pretended to fiddle with the sound equipment, but they were really watching the people come and go. Of course, a customer that came in for coffee at two wasn’t going to stay for a performance at five. Nonetheless, Bomani’s heart stopped every time a potential fan walked out the door.

He needn’t have worried. Groundswell Coffee was hopping by show time. Word was all over the city net, and, whether a live performance spoke to a deep need unfulfilled by the Ent-Ind screens or whether it was the sheer novelty, Revival played to a packed house

It was their big chance.

And it was a big success.

Bomani, Damon, and Jack, Revival’s drummer, played like their instruments were on fire. They owned the stage. Energy in the crowd reverberated with the energy in the band, pushing their performance to an ecstatic level. Every song ended to an eruption of applause.

Sitting quietly at a table in the back, Minerva and Christy were lost in the music.

Even without the aid of the Mnerozia, it was very much the mirror of the night Minerva and Bomani met. Of course, Damon wasn’t the bass player back then; Bomani had been in an entirely different band. And, Minerva didn’t meet Christy until she took her current job. Still, the two friends had been briefed and knew their roles. So, when the first set ended, Damon led Bomani through the rapturous crowd, back to their wives’ table.

“Hey love,” Damon said, kissing his wife, playing it cool as the new rockstar.

“Hi Christy. How’d you like the set?” Bomani asked, proud as a peacock.

“Fantastic!” Christy caught Damon’s eye and gave him a strange look. No matter how well prepped she was, Christy couldn’t get over the oddity of the situation. “Have you met my friend?”

A middle-aged woman in a powder-blue suit put out her hand, “My name’s Minerva.”

Polite as could be, Bomani took the woman’s hand. “Bomani. Nice to meet you.”

The crowd was settling down. Dancers, jumpers, and screamers slowly morphed into normal coffee-drinkers carrying on quiet conversations. Damon sat down beside Christy, and Bomani joined them.

The four individuals, who were usually two couples, sat around the small round table, and the tension grew. Damon ordered himself a drink, and Christy wondered what she’d gotten herself into. At the height of awkwardness, as if on cue, Bomani grabbed a handful of sugar packets. “I can juggle,” he said and threw the sugar in the air. Christy’s breath caught in her throat, and Damon spat out the word “Fool!” But, one packet at a time, the sugar landed in his hands and sprang back in the air.

Minerva’s face broke into a grin. She already thought this gawky guitarist with a black face and bright teeth was cute. She admired a middle-aged man who was still following a dream. As she put her hands together to applaud the juggling, the dancing sugar lost its feet. Packets went flying, and Bomani reached to stop them, knocking Minerva’s hot chocolate in her lap. She laughed and laughed.

“I’m so sorry…” Bomani took a napkin and tried to wipe the hot chocolate away. “So sorry.” But Minerva was still laughing, and her laughter made him grin. You know, Bomani thought, this girl didn’t look half bad. With her face lit up like that — she was pretty.

“So, what do you do, my dear Roman goddess of wisdom?”

Minerva shook her head, amused. “I’m an office manager over at Portland State.” She gestured vaguely, implying the direction of the university campus. “What’s your day job?”

Bomani leaned way back in his chair, tipping it onto its back legs. He didn’t want to tip his hand too soon, so he turned her question back around. “Are you saying ‘office manager’ is just a day job for you?”

“It’s what I do. It’s not who I am.”

Bomani measured that answer and liked it. “I’m a tech at Ent-Ind,” he said.

“That sounds interesting…” Minerva cocked her head to the side, seeing this man in a new light. “So, you make the magic happen.”

The chair levered back to sitting on all fours. Bomani wasn’t sure he wanted to talk about Ent-Ind. He opened his mouth to speak, but it took a moment for the words to form. “Yeah, uh, you could say that.” He turned to Damon, as if looking for an out. However, Damon was showing Christy the lineup for the next set.

“What exactly do you do? Do you get to work with the artists?”

“Uh, no.” Bomani still looked nervous, but he warmed to the subject as he spoke. “The artists — the singers, the musicians, the actors — they all work in separate studios. Guided by directors. I work with the raw talent once it’s digitized.”

Minerva scrunched her eyebrows, confused.

“I get the recordings of the singer’s voices, the dancer’s movement, that kind of thing. Then, I match up faces, styles of expression, tone of voice, musical beat — all those things — I put them together, trying different combinations, until I get a real blend.” By now, Bomani’s hands were moving with his words, and he’d leaned forward in his chair.

“Wow,” she said. “You’re an artist by both day and night.”

“I guess it does take some artistry,” said Bomani, suddenly acquiring a modicum of modesty. He knew he’d been boasting, in his heart if not his words. He felt like a puffed up rooster tonight. And for all his qualms about it, he loved his job. Whether it was right or not, he enjoyed doing it.

“I remember the first time I saw a vid of Van Morrison singing ‘Brown-Eyed Girl,'” he said. “I couldn’t believe he was so young and clean cut. From his voice, you’d think he had long, unkempt, frizzy hair. You’d think he’d been lying in a field all day. But, he sure didn’t look it.”

“And, you keep that from happening.”

“Yep, my job is to make sure the Righteous Brothers look as black as they sound.”

Minerva swirled the remainder of her hot chocolate around the bottom of her mug. She felt a strange reluctance to let the conversation turn towards twentieth century artists, an apprehension that it might stay there, and a sense that she’d heard all there was to hear on that subject. “Have you thought about getting an Ent-Ind contract?”

Bomani looked at her quizzically.

“For your band. You guys are good. And, I bet that working there, as a tech, you’d have an ‘in.'”

“Are you kidding?”

“No, seriously, couldn’t you at least get an audition?”

“Hah!” Bomani slapped his open palms down on the tabletop. “You think I’d want to be an Ent-Ind artist?”

Now it was Minerva’s turn to look quizzical. “Why not? Your guitar playing is heavenly.”

A goofy grin took over Bomani’s face as the compliment sunk in. He relaxed in his chair. “That’s why I wouldn’t want it locked up in some iron barred prison cell of an Ent-Ind contract, Minnie.”

Minerva bristled at the shortening of her name. “What do you mean?”

“Yeah, what do you mean?” Christy added, rejoining the two parallel conversations. “I’ve never understood this part.”

“Well…” Damon started, but Bomani cut him off.

“An Ent-Ind artist can’t perform in public, because he’s licensed his talent to Entertainment Industries. It’s not his anymore. But, that’d be okay. If that were the only thing. Here’s the real killer: they lock the artists up in isolated studios when they work. Actors don’t act together. Dancers don’t dance together. And bands never play together.

“You’ve been enjoying Revival tonight? Well, what makes Revival great is the synergy between Damon, Jack, and me. It makes it great for you, and it makes it great for us. Ent-Industries doesn’t have that. It eats up talented artists and spits out two things: normal people who you can run into on the street and synthesized gods who you’ll only ever see on a vid-screen. Well, I’ll be damned to hell if I’m gonna give up my talent,” he spat the word out, “so that my fingers can grace the next Ent-Ind god of music as he plays guitar.”

“Hear, hear!” Damon cheered and raised his drink. But the women both looked a little shocked. Eventually, Christy shrugged.

“It’s a good thing you both like your day jobs,” she said. “‘Cause, you’ll never support yourselves at it this way.” She gestured to the crowd around them.

“Yeah, but baby,” Damon said, looking at the crowd, “this is what it’s all about!”

Christy shook her head and ruffled her husband’s hair. “Speaking of which…”

“Yeah,” Damon checked his watch, “it’s about that time.”

The men rose from their seats. They could see Jack beckoning them to the stage. The crowd was crackling with anticipation, but all Bomani could think about was that he seemed to have upset Christy’s friend Minerva. “Shall the four of us get together for a late dinner after the second set?” he asked. He was sure he could patch it up then. His views could come on a little strong… But, this woman looked like she could understand him. With time.

“Sure,” Christy answered. Bomani smiled his wide grin and turned to follow Damon. “What’s wrong with you?” Christy asked, elbowing Minerva. “You’ve turned all stony faced.”

“I think I’ll duck out before dinner.” Minerva continued despite Christy’s open-mouthed shock: “You can stay, but I don’t want to spend another minute with that man!” Her voice rose as she spoke. “Did you hear him? He’s a complete hypocrite. And a coward. Working for a company he hates? I could never respect a man like that. And, honestly, still talking about 1960s music after all these years?”

Bomani had turned around and was watching now, but Minerva didn’t care. She didn’t know this man, so what did she care what he thought? He sounded like he needed a severe talking to, and she felt like the person to do it. Though, she didn’t know where the feeling was coming from.

“He acts like a prima donna, like his music is more serious than anything done by Ent-Ind, but he’s still copy-catting stuff done over a century ago.”

Christy wanted to defend Minerva’s husband, but she knew that the first song of the second set was “Louie, Louie.” She looked down at the tabletop, avoiding the wrath in Minerva’s eyes and the hurt in Bomani’s. “Let’s get out of here,” she said. That wasn’t part of the plan, but right now her priority was damage control. Minerva and Bomani would get over this fight, but, if Revival didn’t get back on the stage, Kenny might not ask them back.

Christy’s worries about the band, however, were completely unfounded. Revival was an unequivocal success, and Kenny invited them to play Friday and Saturday nights at Groundswell indefinitely.

The band had a late dinner together to celebrate. Damon and Jack crowed about their coup. Bomani tried to join in, but his heart wasn’t in it. After all their work for this success, all he wanted to talk about was that girl with Christy. He slept on Damon and Christy’s couch again that night.

Christy stayed over with Minerva. The two women looked at old photo albums and talked about the good times Minerva’d had with Bomani until her memories were almost entirely back.

She swore she’d never take that damn drug again.

Time heals all ills, or so they say. Neither spouse, however, wanted to wait for time. By arrangement, they met at Kenny’s coffee shop the next morning. After the late night net-buzz about Revival, Groundswell was the place to be on a bright Sunday morning. They would have had trouble finding seats, but Kenny had heard what happened and held a table for them.

Over coffee and croissants, they looked at each other. Nervously. Until the last drops and crumbs were gone, neither ventured to speak. Bomani kept a stiff upper lip, and Minerva kept letting her hair fall in front of her face. She felt shy. Their hundred-and-twentieth anniversary hadn’t turned out to be a second enchanted evening, but this morning felt as awkward as a first date. And, honestly, she felt guilty. For the things she’d said. Worse, for knowing she’d meant them. Also, she felt sad. She’d ended up missing out on Revival’s big opening, just as she had feared.

“So, is this it?” Bomani asked. “After a hundred and twenty years, we have nothing in common any more? No more use for each other?”

There was a quaver in his voice, and it broke Minerva’s heart. Between the band and their anniversary, this should have been a happy day… The contrast with what “should have been” only made it worse.

Minerva was out of her seat and in Bomani’s arms within seconds. She heaved dry sobs, pressed against his stiff chest, unyielding arms. She buried her face in the curve of his neck, fighting off hot tears.

For all his nervousness, his vulnerability, his hurt pride… Bomani couldn’t resist that.

When Minerva felt his arms tighten around her, she found strength again. She pulled away until she could look him in the face. Kneeling by his chair, she cupped her hands around his face. For all his weakness, his infuriating, hypocritical passion — everything she’d berated him for the night before — he was her man. “I have every use for you,” she said. “I wouldn’t know what to do without you. You know that.”

He pulled her hands from cradling his face and held them in his lap. “I’m too old to change,” he said, and he looked old as he said it.

“I don’t want you to,” she said.

“But you hate it… the perennial sixties music… the…” he would have continued the list, but it made Minerva cringe.

“It annoys me. I admit that.” She knew she should comfort him, but it was hard. “How could two people live together for more than a century and not get annoyed with each other?”

“I don’t get annoyed with you.”

That knocked the wind out of her, because she knew it was true. “Well, you’re a saint,” she said. “To me. And, that’s why I forgive you for everything else that’s wrong about you.” Minerva sat back in her chair, fiddled with the dishes. How did she ever deserve a man like him? And yet… She couldn’t help remembering how he’d looked to her the night before. She’d seen him with unbiased eyes, and she hadn’t liked what she’d seen. Or was unfamiliarity a bias too?

“You don’t regret marrying me?” Bomani asked. Minerva looked at him strangely, so he continued, faltering. “That’s what I heard in your voice last night. Regret.”

With a deep sigh, Minerva said, “I could never regret that.” It was the right answer. The memorized answer. The automatic answer. There was a good reason for it being so. “What I really regret,” she said, “is last night.”

“Don’t regret that,” he said. “The band was a huge success, and we’ll have more anniversaries. I know you missed the second set, so we’ll play the same one next week. You can hear it then.”

Of course, it wasn’t the night she regretted so much as what she’d learned. Bomani had grown into a middle-aged sell-out, and she’d become a judgmental woman capable of despising him. She would have to choose not to. And she would have to live with the knowledge.

Bomani held her hands in his, rubbing circles with his thumbs. Minerva still loved him, his band was a success, and that was all he cared about. Could it be he was more used to the rocky feelings and strange insights brought on by inconstant memories? Or maybe, his love was just simpler than hers. “Next year, we’ll go to New Kokomo,” he said, “okay?”

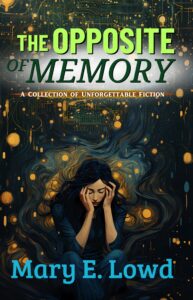

Read more stories from The Opposite of Memory:

[Previous] [Next]