by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in The Rabbit Dies First, January 2019

The lights had gone out ten minutes ago. The sound of the air circulators had shut down too. Narchi didn’t know what was happening, but she was scared. Power shouldn’t shut down on a space station. Yet, she had to hold herself together. Her lapine roommates had left her babysitting nearly a dozen of their children. When she’d agreed, she hadn’t expected it to be in the dark.

Tiny lapines with strong legs and big feet bounced off the walls in their quarters. Literally. Fuzzy bodies rocketed past each other in every which direction, occasionally thudding into the broad thick-hided side of their buffalo-like host. Narchi let out a soft, “Oof!”, whenever one of the lapine kits knocked into her, but she didn’t mind. Not really.

Narchi had been sharing her quarters with an extended family of uplifted lapines for several months, ever since the rabbit-like sentients had escaped from their homeworld.

So, Narchi was used to a certain amount of frenetic bouncing around her. But usually, it wasn’t in the dark. All of her instincts told her that darkness meant stillness. Her species were plains-folk from a planet with five moons. So, she’d never before experienced the type of darkness that happens on a space station during a black out. It was a total darkness, the kind that can only be found deep inside a cave on most planets, and it didn’t seem to bother the lapine children. Their species had been uplifted from burrowers.

Narchi wasn’t an expert on child-rearing, but bouncing in the dark seemed like the kind of activity that the adult in charge was supposed to stop. Since she was the babysitter right now, that meant her.

With a bellowing, bovine voice, Narchi mooed into the darkness, “Settle down now! No more hopping!”

Lapine giggles erupted around her. The hopping didn’t stop. In fact, from the increased fuzzy pummeling of her side, Narchi could only conclude that they’d used her moo as a way to target her in the total dark.

Narchi sighed. This would not do. The little lapines were going to break things, knock over furniture, and hurt themselves if they kept this up. They needed a better activity.

Going against her own instincts, Narchi felt her way through the darkness, moving slowly and touching everything with her hoof-hands to keep from bumping into things. That is, things other than the little lapines, some of whom had clung onto her hunched shoulders for a ride. Finally, she found the drawer where Roscoe, one of the adult lapines, kept his knitting. She pulled out a ball of the Eridanii arachni-silk yarn and started tying loops into it at regular intervals, tricky work in the dark.

Narchi hooked her own hoof-hand through one of the loops, held the knotted mess of yarn out and mooed, “Come over here, little ones. Each of you, find a loop of yarn, and hold on tight with your paw.”

A chorus of chirpy voices, assaulted her with questions:

“Why?”

“Is it a game?”

“Are we going somewhere?”

As they questioned her, Narchi felt little tugs on the yarn that meant the lapine children were grabbing the loops. “Yes,” she mooed. “We’re going on a walk.” The lights might be down in their quarters, but there had to be light, at least minimal light, in the more communal parts of Crossroads Station. And if they got out of their darkened quarters, maybe Narchi would have a chance of finding out what was going on.

Before leaving their quarters, Narchi placed her hoof-hand on each of the lapine children’s heads in turn, between their long ears. She counted fifteen; that was everyone. “Stay close,” she said.

The strange parade — a sentient buffalo followed by more than a dozen sentient bunnies, following her like little ducklings — lumbered and hopped their way down the hallways of Crossroads Station’s residential quarter in the dark. Narchi held her loop of yarn with one hoof-hand and trailed the other hoof-hand along the wall, feeling her way.

“I see something!” one of the little lapines squeaked.

Narchi still couldn’t see anything, but the lapines’ eyes were better than hers. Their ears too. All their senses seemed to be stronger. Sometimes, she felt like a giant dull lump around the bouncy little things.

“I see it too!” a chorus of little lapines cried.

Suddenly, Narchi found herself tugged forward by the yarn as all her little bunny-ducklings hopped towards the dim source of light.

“It’s the Merchant Quarter!” one of the lapines chirped. “Can we get Hegulan churros?”

The other children started chirping about all sorts of other treats they wanted to buy, and Narchi realized she’d left her ident card in their quarters. She also realized that she had no idea how to find her way back to their quarters through the dark. “Let’s find out what’s going on first.”

All the little lapines moaned in disappointment.

The Merchant Quarter was extra busy, aliens of all shapes and sizes milling together, staring up at the windows that curved over the wide hallway that was always filled with food stands and vendor stalls.

The stars had never looked so bright. They twinkled in the darkness. The only light came from a few emergency lanterns embedded along the walls, so the entire quarter was trapped in a strange dim twilight.

Narchi gathered her lapine wards in close, counting from one to fifteen repeatedly, checking to make sure none of the long-eared children had strayed.

A double-winged avian alien — an Eechee — approached the funny group and cawed to Narchi, “You look a little overwhelmed.”

Several of the lapine children had climbed onto Narchi’s wide back again. One of them had climbed all the way up to sit on her shoulders, holding her two crescent horns like handlebars. “You could say that,” Narchi agreed.

“This is Roscoe’s family, isn’t it?” the Eechie cawed. “I’m Chorif. He’s gone on salvage trips with me.”

“What happened?” Narchi mooed. “Does anyone know?”

An ursine alien, large and furry like Narchi, heard their conversation and joined in: “I heard it’s a space storm.”

“An electro-magnetic pulse from a solar flare,” offered an orange-furred canine alien, one of the station’s most common species.

Somehow the darkness and uncertainty drew everyone together. Aliens who would usually never talk to each other, too busy with their own lives, now had nothing better to do than stand around and speculate about the station-wide power outage.

“How long do you think it will last?” Narchi asked, her head tilting wildly to the side as the lapine on her shoulders decided to try steering her using her horns.

Chorif laughed at the sight, a cackling cawing sound. “You’ve got your hands full, haven’t you. How’d you end up in charge of so many of Roscoe’s younger kin?”

The little lapine on Narchi’s shoulders piped up: “We share quarters! She watches us when the b’dults are busy!”

“Roscoe and their other parents got a job checking the sound-proofing and acoustics on a recording studio cruiser that belongs to some visiting reptilian pop star,” Narchi explained. “Good ears, you know. They left right before the power went out.”

“Star Shaker — I love her music,” Chorif said, ruffling out the feathers in her lower wings. “I know where her ship’s docked. Want me to take you there?”

Narchi eyed the restless little bunnies huddled around her, ears drooping. “I think what we really need is…” She was reluctant to say it around them, but whispering would do no good. Their ears could hear anything she said. “A snack.”

Drooping ears perked up, and fifteen little noses started twitching eagerly. “Oh, yes, please,” said many little hopeful voices.

A green-skinned amphibian alien with a long snake-like tail instead of legs slithered over and said, “Head over to the grav-bubble playground — the grav-bubble play-structures are down, but all the merchants with quickly perishable food are giving away what they can’t sell fast enough.”

“Thank you,” Narchi said. She knew the way to the playground.

The buffalo led her herd of bunnies through the unusually friendly crowds, accompanied by Roscoe’s double-winged avian friend. When they got to the playground, they found that all manner of alien children were playing low-tech games of chase and tag. Merchants of all species plied them with sticky melting frozen treats. For the little ones, a station-wide power outage was heaven.

Now that Narchi’s wards were under control and busy playing, she stuffed the Eridanii arachni-silk yarn in her pocket. The terror she’d been holding at bay, inside a knot deep in her stomach, flowed out and filled her body. It hadn’t been safe to feel it before now, not with all the little bunnies depending on her. “No one answered any of the real questions while I had fifteen babies clinging to me,” Narchi mooed softly to Chorif. “How common is this? How long will it last? Will it get fixed? What happens if it doesn’t?”

“You haven’t been a citizen of space long, have you?” Chorif cawed, watching the lapines play.

“Less than a year. I was picked up by a passing research team; my species hasn’t made it to space on our own yet.”

“Power outages in space are rare and bad,” Chorif cawed, feathers ruffling all over her body. “To knock a space station like Crossroads out, we’re dealing with a one in a million storm. The EM waves had to be powerful enough to blow out everything but the most protected systems; that means even those of us with our own spaceships — I have my own little cargo hauler — can’t wake up our ships to get out of here until the storm subsides. Either the waves die down in the next few hours or…”

“Or people stop being nice to each other,” Narchi said.

“I don’t know about that. If no one has anywhere to go, there’s not a lot left to fight over.”

The thought settled over them somberly. Narchi wondered if she should take the young ones looking for their parents, so they could all be together. She tried not to think: “die together.” The lapines seemed so powerful with their acute senses most of the time, but right now, they seemed small and delicate. Narchi’s large body was built for weathering droughts and storms. She didn’t want to watch these bunnies die.

She didn’t want to die. Suddenly, Narchi wished that she’d sent more radio messages home during the last year.

“I think it’s better if we stay here,” Narchi said. “The little ones are happy playing. I’m sure Roscoe and the others will find us.” On an impulse, Narchi asked her new friend, “Do you have any regrets?”

“Other than being here today instead of on some random lush forest planet?” Chorif cawed, folding her wings up tight.

“Other than that.”

“Not a one.”

Narchi nodded her heavy buffalo head. “That’s a good way to live.” And when she thought about it, she didn’t really have any regrets either. Not big ones. When given the chance, she’d taken the risk and left her homeworld. She’d seen more of the universe than any other member of her species.

The lights flickered, darker, brighter, darker, and finally all the way out. For a few startling heartbeats, the entire merchant quarter was drowned in velvet darkness, lit only by the twinkling stars.

Then the metal floor hummed under Narchi’s hooves, and the entire station vibrated back to life. The lights flashed on, blindingly bright. Cries of childhood despair filled the playground — their power outage adventure was over. But the rest of the merchant quarter gasped, hundreds of individuals letting out a breath of relief as if one.

“How about you?” Chorif cawed. “Any regrets? Cause it looks like you’ll have a chance to do something about them.”

Fifteen lapine children swarmed the buffalo sentient, tugging at her shaggy fur and hopping around her hooves. “The gravity bubbles are working again! Come play with us!” Just as quickly, they swarmed off and, one by one, hopped into the grav-bubbles to spin and float around the playground.

“I feel like I should have realized something important…” Narchi scratched at the base of her left crescent horn. “Like it’s time to go home. Or to explore the universe further.”

Chorif shrugged her upper wings. “Facing death doesn’t have to be deep.”

“Maybe just that living on a space station isn’t safe…?”

Again, the Eechie shrugged, this time with her lower wings. “This storm was one in a million, remember? Is anywhere really safe?”

“I guess not…” Narchi watched the little lapines playing, and all she could think was that it looked fun. And she was happy living on Crossroads Station.

But she was also happy that the power was back on.

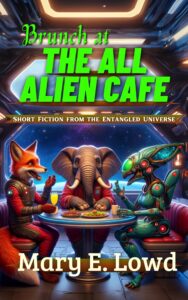

Read more stories from Brunch at the All Alien Cafe:

Read more stories from Brunch at the All Alien Cafe:

[Previous] [Next]