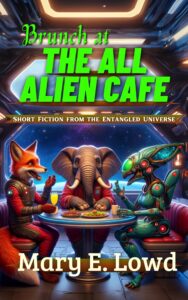

by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Brunch at the All Alien Cafe, March 2024

Like a delicate crystal vase, the hard shell of Am-lei’s chrysalis cracked, spilling out the furled up, new-grown, riotously colorful wings inside. Still wet, the wings hung from her changed body, pulsing with life, heavy and dragging her down, out of the chrysalis that had held her, dormant, for the last month.

The month had passed like a dream. Am-lei remembered her body itching all over, and her mouth overflowing with gooey silk-spittle. She remembered climbing up the walls of her room and gluing her feet to the ceiling as her squishy, green caterpillar skin split down the middle, shedding like a winter coat on a hot day, revealing the hardened chrysalis that had developed underneath, her new outer shell, as the rest of her melted and mutated inside.

Those memories were sharp and clear, and even to her, a little horrifying. It had felt natural, but she’d grown up with enough mammalian, avian, and reptilian friends to know that your face splitting open and peeling off is supposed to be the stuff of horror films.

But the memories afterward… Her mother visiting every night, and reading stories to her. Her best friends — an elephantine alien and canine alien — coming and playing board games beside her dormant shell. Those images were fuzzy in her mind, seen through the obscuring veil of her chrysalis.

As Am-lei rested on the bed beneath where her broken, twisted shell of a chrysalis still hung, she sorted through the memories and the dreams, trying to figure out what had been real, and what she’d imagined. Until hunger overcame her.

“I haven’t eaten in a month,” Am-lei tried to say, but her mouth was so different that the words came out as a jumble of incoherent, fluting sounds. Pretty but ineffectual. She lifted a talon to her face. Her arms were long now — they’d been stubby before — and they ended in hard, exoskeleton-covered talons, not pudgy caterpillar hands. But her face was even more different.

The wriggling mouthparts she remembered were still there, but smaller, more vestigial; and her mandibles had shrunk to mere relics of what they used to be. All of it made way for her new mouth — the long, curling, flute-like proboscis. Like her mother’s. She had an adult body now, with an adult face, and an adult mouth.

Her mother, Lee-a-lei, appeared at the door, holding a goblet of golden liquid. The ambrosia adult lepidopterans drank.

Am-lei accepted the goblet greedily. She unfurled her proboscis clumsily, taking three tries to land the end of it in the goblet where she could suck up the sticky, sweet goodness through her new mouth like a straw.

The golden fluid settled in her stomach, soothing the roar of hunger, but leaving her uneasy. Everything felt strange and off. She’d never thought about how her stomach or limbs or most of her body really felt before… She’d simply lived in it, and all those parts had done what she told them to do. But now, she went to move her arm, and since it was longer, it moved farther and faster than she meant. She tried to speak, and the parts of her face fell all over each other, trying to fulfill the commands sent by her brain, but not quite getting them right.

Lee-a-lei sat down beside her clone-daughter, taking back the empty goblet. “It takes a while to settle into your new body.”

“It must have been scary for you,” Am-lei said. Her mother had been rescued as an infant caterpillar from a crashed spaceship and raised by the human woman who found her. Neither of them had known she would go through a chrysalis phase. Nor that lepidopterans generally cut off their wings during a coming-of-age celebration after emerging.

Lepidopterans considered their wings vestigial. Without any adult lepidopterans around, though, Lee-a-lei had lived with the inconvenient yet beautiful appendages weighing her down for many years.

Lee-a-lei traced the dark veins on Am-lei’s quivering, still-drying wings with the tip of a talon. “So beautiful,” she said.

“Do you still miss yours, Mother?”

“Sort of.” Lee-a-lei drew her talon back, as if the bright pools of color in Am-lei’s wings could burn her. “Most humans look at me differently now.”

“You’re just a big bug, not a beautiful butterfly.”

“Right.”

Am-lei could read the sadness in her mother’s slouched arms, all four of them, and the tight, pinched curl of her proboscis. “To hell with humans, though, right?” Am-lei said, trying to cheer her up. “Well, I mean, except for Grandma.”

“She’ll be here shortly,” Lee-a-lei said. “To help us get ready for the party.”

* * *

All of Am-lei’s school friends came to her Wing Day party. Children of all species — a perfect cross-section of Crossroads Station’s inhabitants — crashed through the lepidopterans’ apartment, shouting, tussling, carousing, and generally having fun.

Lee-a-lei and her adoptive mother, Amy, put out trays and bowls of snacks, and kept refilling them as the guests devoured the tasty morsels. Toasted berry-buds, kernels of soft cheese, fried sweet breads, and smoked fingerling fishes. Amy had been cooking all night, ever since she’d heard that Am-lei’s chrysalis had begun to crack.

The star of the party bounced and floated through the room, flapping her vestigial wings or trying to glide with them. Her best friend, Jeko the elephantine alien, held a flashlight in her trunk and shone its beam through Am-lei’s left wing, casting pools of colored light all over the assembled children who oohed and ahhed at how pretty they were. Like stained glass windows, come to life.

When the time came for her wings to be cut off, Am-lei didn’t flinch or hesitate. Though, both her lepidopteran mother and human grandmother did. The knife sliced through the soft flesh of the wing, along the hard edge of her exo-skeletal carapace, as smoothly as through warm butter. Lee-a-lei cut off the first wing, leaving her daughter lopsided and laughing, a wondrous, fluting sound with her new mouth; Amy took the knife and cut off the other.

* * *

After the last guest left, Am-lei curled up on the couch, all four, long arms wrapped around her swollen abdomen and groaned.

Amy worked on clearing away the remnants of the food she’d brought, but Lee-a-lei came over to kneel beside her daughter, who looked more like a mirror of her today than ever before. “What’s wrong, love?” she asked. “Do you miss your wings? You didn’t get to keep them for very long. Not like I did.”

Am-lei laughed like a squashed bagpipe, less musical and more a snort of derision. “Are you kidding? Those things were crazy awkward. I don’t know how you put up with them all those years.”

“Are you sad the party’s over?” Lee-a-lei asked, gently running a talon along one of Am-lei’s curved antennae. “Or maybe you’re hungry and need more nectar?”

Am-lei groaned. “No, I’ve eaten enough.”

Amy stood by the door, arms filled with containers of leftovers, looking sympathetically at her alien daughter and granddaughter. Just an old human woman who loved her progeny as much as any grandmother could, regardless of their wildly different bodies. “I’m going to take the leftovers home, and see you both tomorrow. Okay?”

“Wait,” Am-lei said, “you’re not taking all of them are you?” Her grandmother and the armful of packaged up tasty treats reflected in every facet of her silvery, disco ball-like eyes.

“Well, yes,” Amy said. “I didn’t figure you’d have much use for them.”

“But…” Am-lei objected, confused.

“You weren’t eating the snacks for the guests, were you?” Lee-a-lei asked, her own proboscis curling tightly and antennae waving worriedly.

“Well… yeah?” Am-lei groaned again, as a sharp pain in her abdomen doubled her over even more tightly.

Human grandmother and lepidopteran mother exchanged a glance.

“Oh dear,” Amy said, sighing. “You’ve got a long night ahead of you. Good luck.” And she left the two lepidopterans alone. The only two butterflies — albeit without wings — on a space station full of mammals, avians, and reptiles.

“Honey, have you ever seen me eat solid food?” Lee-a-lei asked.

“Well, no… but… I thought you just didn’t like it?”

Lee-a-lei sat on the couch beside her curled up daughter and stroked the gleaming, new carapace with gentle talons. “I guess I should have talked about this more,” she said. “I hadn’t realized…” With a deep sigh, she straightened out her antennae, steeling her resolve. She hadn’t talked enough about her past before, so she would have to talk about it now. “I’m sorry, I guess it was just too painful for me. Of course, I ate solid food as a caterpillar, and then… because I didn’t know better, I kept eating it after my chrysalis.”

Am-lei didn’t like where this was going. Part of her knew. Part of her had known before she popped the toasted berry-buds in the vestigial mouth under her proboscis. Part of her had felt her body rebel against their solidity. Their delicious, complicated texture. But she didn’t want to believe it, so she’d choked down kernels of cheese and pieces of sweet bread too. They’d tasted as delicious as ever. Maybe even more delicious, because they’d also tasted… dangerous. Like she wasn’t supposed to be eating them, and that extra edge had made them special.

“Adult lepidopteran stomachs aren’t suited to solid foods.”

Am-lei hated hearing her mother say that sentence out loud, as if refusing to say it would make it untrue. “Then what I am I supposed to do?” she wailed, remembering every food she’d ever loved; every meal that she’d shared with her friends; every moment of joy she’d felt while munching on a simple snack, letting her wriggling mouth parts play with the toasty leaves of a berry bud, pulling it apart and savoring each leaf as she ate it.

She was never going to do that again. The meals she’d eaten before hardening into her chrysalis should have been her last. And based on how her swollen abdomen felt — like it would explode any moment and leave her to die — the ones she’d eaten today really would be her last.

The part of her life when she got to eat toasted berry buds, and soft, oozy cheeses, and sugar encrusted rolls were all over.

Birthday cakes at her friends’ parties.

Slurping up long spaghetti noodles.

Her best friend Jeko throwing popcorn at her with her trunk, and Am-lei catching it with her mouth parts.

It was all over.

She hadn’t expected it to ever end.

“You’ll drink nectar,” Lee-a-lei said, simply. And it felt profoundly unfair.

Am-lei groaned and rocked her abdomen. The swaying motion seemed to help. The groaning helped too — it was half pain, and half disconsolate loss.

After a while, her groaning and the pain causing it subsided a little, and Am-lei said, “How did you… figure it out?”

“It took years,” Lee-a-lei admitted.

“Years?” Am-lei asked in alarm. She couldn’t imagine suffering this kind of pain for years. She desperately didn’t want to give up solid foods, but she also couldn’t imagine letting another piece of solid food past her mandibles again. Not ever. This pain was too much.

“I was very sick for the first few years after my chrysalis,” Lee-a-lei said. “It took months and months of trial and error, experimenting with different foods and combinations, sometimes spending days in the medical center under observation, before I figured out what I could safely eat. In the end, it was your grandmother who figured it out, actually. Not me. I don’t think I wanted to see the truth.”

“I can understand that.” Am-lei curled her proboscis tightly. She hated this — both the pain and the change. But what her mother had been through sounded so much worse.

“Did you see the gift your grandmother brought for you?” Lee-a-lei asked, stroking Am-lei’s antennae again.

Am-lei lifted her head from the arm of the couch, sparkling disco-ball eyes trying to see where there might be a present lying around, waiting for her. “Wing Day isn’t really a gift-giving holiday,” she said.

“I know,” Lee-a-lei agreed, getting up from the couch. She went over to a table by the door and lifted a small rectangular box, about the size of terran grapefruit, wrapped in colorful paper. She brought it over and offered it to her daughter.

Am-lei sat up, intrigued enough by the gift to forget the ache in her abdomen for a moment. She tore off the paper and found a mechanical object inside.

“It’s a travel-size blender,” Lee-a-lei explained. “I used to carry one with me, when I was still adapting to… an adult lepidopteran diet. I’ll warn you — most foods that your friends eat won’t be nearly as good once they’re blended. But…”

“It lets me participate.”

“Yeah, also, it lets you…” Lee-a-lei shrugged her four arms in frustration. “I don’t know. It made it easier to let go? If you can still eat the food, but only in a way where it doesn’t taste good… it’s easier to lie to yourself and pretend you just don’t like it anymore.”

A tentative, fluting laugh came from Am-lei. “That’s kind of sad, Mom.”

“I know. It still helped. And you know, you can still drink all the beverages that your friends enjoy — tea, coffee, smoothies, soda pop.”

“Huh,” Am-lei mused, “I wonder how carbonation feels now.” She ran a talon along the curve of her proboscis.

“Want to find out?” Lee-a-lei’s antennae curled toward each other, sketching out a vaguely heart-shape in the air. She knew that carbonation was delightfully ticklish inside an adult lepidopteran proboscis, even more so than in a caterpillar-stage mouth. It could also be soothing on a swollen abdomen, distended by solid foods it wasn’t designed to process anymore. “I’ll get you something, okay?”

Am-lei put the blender down on the floor next to the couch and laid herself back down again. “Yeah, Mom, thanks.”

When Lee-a-lei brought her daughter a tall glass of sugary, fizzy soda pop — her favorite flavor, Centauri Citrus — the newly adult-bodied lepidopteran took the drink in her talons, unfurled her proboscis into the glass, and felt the tickly bubbles all over both the inside and outside of her new straw-like mouth. The sweetness and tart bite of citrus was more intense flowing through the curve of her proboscis than it had ever been in her caterpillar mouth, and while she sipped it down, she thought about all the foods she used to enjoy, almost flinching at the thought of them now.

She would have to learn the difference between the foods her eyes coveted and the ones her stomach craved. Hopefully, eventually, she could get them to align. She would shed her desire for the foods of her caterpillar stage the same way she had shed her wings today. Wings that were beautiful… but ultimately useless to her.

At least, while she was settling into this new way of life, she’d be in her cool new body with a shiny exo-skeletal carapace, long limbs, and a proboscis that made her voice sound like a beautiful, musical instrument.

Read more stories from Brunch at the All Alien Cafe:

Read more stories from Brunch at the All Alien Cafe:

[Previous] [Next]