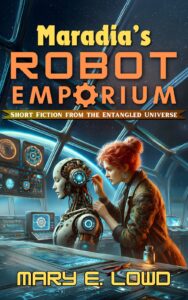

by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Maradia’s Robot Emporium, March 2025

Rariel 77 had entire closets of different bodies zhe’d built for zirself, and zhe liked switching between them. Sometimes, you want a classic robot body — boxy, straight lines, gleaming metal. You know, that whole deal. But sometimes, an AI simply needs to be able to go incognito and blend in with all the biological sentients around. The most common species on Crossroads Station were the Heffen (a sort of canine alien, kind of like anthro red wolves) and after that humans. Rariel 77 had very nice android bodies in both of those flavors. Zhe also had some much more abstract choices for when zhe was feeling whimsical or wanted to go on a spacewalk or do some other more exotic activity.

Zhe loved having a different body to suit every mood, and zhe loved designing zirself new bodies. What Rariel 77 was realizing zhe didn’t love was learning to operate those new bodies.

Every new body came with a learning curve.

Sure, tentacles with suction cups on them like an octopus’s arms sounded like fun… until Rariel had to learn how to manage eight limbs at the same time when each one of them bent in any direction at any point — as opposed to simply bending in two directions at two or three points. Multiplicatively many more variables to control. If zhe were a biological lifeform, it would have given zir a headache. Since zhe was an AI who could remove or replace any heads zhe chose to wear at will, the sensation was more abstract but no less annoying.

And so Rariel 77 decided it was time to outsource some of the work. Why learn to control a body zirself when zhe could install a simple brain kernel into the body’s empty brain, turn it on, and let the body practice controlling itself instead?

Rariel set up a sort of playpen for the body zhe intended to try this strategy on first — a safe space where the body couldn’t get into any real trouble or cause any real harm. When Rariel’s own creator — a human roboticist named Maradia — saw the playpen, she scrunched up her eyebrows in some sort of surprise or confusion and asked, “What’s the crib for?”

“It’s a training space for my new bodies as I build them,” Rariel answered from a speaker system installed in zir quarters. Zhe wasn’t embodied in a robot form right then, preferring to spend some time relaxing in the freedom of the Crossroads Station networked computer system. Zhe had zir own space in the computer system as well — several devoted hard drives that zhe could withdraw to if zhe didn’t feel like dealing with the more public spaces of the shared network. Either way, it was simply nice sometimes to stop worrying about the work of controlling a body.

“How’s it work?” Maradia asked, unbothered by her AI offspring’s ethereal status. Maradia was more than used to Rariel moving from one body to another and sometimes eschewing bodies entirely. In fact, it seemed like zhe was doing that a lot lately, ever since zhe’d decided zhe didn’t feel comfortable attending the robotics club Maradia ran. Maradia was a little worried about how unfriendly her own robotics club had turned out to be for an actual robot in attendance… But she wasn’t worried at all about Rariel, who had responded by simply founding a new robotics club of zir own. She was overawed and inspired by Rariel.

Maybe sometimes, in the depths of her heart, Maradia was afraid of Rariel leaving her behind and not looking back to zir mother — a slow, meat-based biological creature — waving to zir as zhe left. It had happened to Maradia before with robots and AIs she’d designed. She was always proud of them, but sometimes, she was heartsore from the way they moved on to places she couldn’t follow.

Maradia wasn’t always sure what purpose she served anymore. She’d already made so many AIs and robots that now her creations — children of a sort — were all busy making their own advances and creations, and all that was left for Maradia to do was watch and hope her silicon children would still deign to notice their lumpy biological mother sometimes.

While Maradia was worrying about her role in a universe that seemed increasingly okay without her, Rariel was busy inventorying all of zir closets of bodies, ranking them for suitability for testing out zir new scheme. Zhe was loathe to waste time testing zir new plan on a body zhe had already gone to the trouble of learning to operate zirself, but it was also the best way to run a truly meaningful experiment. Repeatability and control groups and all that jazz.

If Rariel ran the first test on a body zhe could already operate, then zhe could compare the results that the kernel program developed with zir own practiced subroutines and make sure they were up to zir standards. That would be the scientific way to do things. However, if Rariel started with an entirely fresh body — something new and exciting that zhe’d only recently finished building and never tried operating from the inside yet — then zhe could jump straight to the good stuff.

So, the real question was: did Rariel want to do proper science… or just crash zir way forward and see what happened?

The real world was already too painfully slow. Rariel didn’t have patience for running proper experiments when what zhe really wanted wasn’t to do science but just to build things. So, zhe picked the body zhe was most excited to try out — a chameleon-like body that had a fairly simple quadrupedal structure but with a slinky, flexible quality and skin that could change texture and color at will. Rariel was excited by the prospect of being able to blend in and camouflage zirself, but zhe also knew it would be a royal pain to learn all the little fiddly details of controlling the color-changing skin.

Rariel loaded a kernel program into the body’s empty brain, designed with a simple directive: move! And then asked Maradia to place the body in the crib before turning it on.

As soon as the chameleon body was in the crib, its four legs started pedaling ineffectively, and its skin flickered from one color to the next erratically — azure blue, gleaming gold, deep dark purple, and then a whole range of different greens. All the colors of the rainbow splashed across the chameleon-body’s skin while it floundered about.

“It doesn’t look like your program is working very well,” Maradia observed.

“Not yet,” Rariel answered over the speakers as they both watched the chameleon ram its head repeatedly into one of the walls of the crib. “But it’ll learn.”

After a few minutes of watching the chameleon’s surprisingly mesmerizing motion, Maradia asked, “Have you thought about what it will feel like to absorb a splinter personality into your programming?”

“It’s only a simple motion-centered program,” Rariel replied, untroubled. “I plan on leaving it in the body’s brain between uses, so I won’t absorb it. I’ll simply share the brain with it and control it as a subroutine. It will be more efficient that way, keeping my own programming streamlined. I don’t need to waste code on motion-controlling subroutines I won’t be using most of the time.”

Maradia’s eyebrows raised in a way that Rariel recognized as meaning she had doubts but was choosing not to voice them. Rariel had seen this expression a lot during zir own development. “You have doubts,” zhe said, preferring to make the subtext text.

“I find that programs tasked with learning have a way of learning whatever they can, not just what you plan for them to,” Maradia said. “Don’t tell Gerangelo about this plan of yours if you don’t want to stir up trouble.”

Rariel had been ready to dismiss zir mother’s concerns, because organic lifeforms rarely understand the complexities of existence as an AI. Even the well-meaning ones who really try. However, Gerangelo was a pillar of the robotic community on Crossroads Station. He was a robot who never conformed to organic social standards, and he was personally responsible for freeing a good half of the robots on the station from the shackles of organic ownership by educating them about the Sentience Tests and advocating for their right to take them.

If something needed to be kept secret from Gerangelo, it usually meant that it infringed on robots’ rights.

Was Rariel doing something wrong here? Zhe wondered, but zhe didn’t see how. Zhe was experimenting with zir own bodies and zir own code, simply partitioning off a small part of zirself at a time. Zhe decided zhe would wait and see how it played out before worrying too much.

* * *

Over the next few hours, the chameleon-body’s ineffective pedaling and floundering gradually became more coordinated walking as it chose to plod around the edges of its confines in little circles. The erratic color changes of its skin began showing more complicated patterns, and after a while, it even started turning approximately the same shade as whatever it had just bumped into, almost as if trying to apologize to the crib walls by mimicking them.

Maradia didn’t stick around — organic lifeforms have a confusing way of being both more and less patient than their digital counterparts, since they’re not able to divide their consciousness up so easily.

Rariel on the other hand devoted a portion of zir consciousness to monitoring the chameleon body’s antics while letting most of zir processing power keep busy with a plethora of other, more entertaining pastimes. For one, zhe was deeply involved in a game of Starsplosions and Spacedroids that another member of zir own robotics club — one specifically for robots — had been leading. Since all the members of the game were AI or robotic lifeforms, they were able to keep the game running as a background program most of the time, and their pretend adventures had grown to epic proportions. An organic player of the game would never have the time — an equivalent of hundreds of years of organic processing power — to completely remake the universe of the game in the way that Rariel’s campaign had.

When Maradia did come back to check on how Rariel’s experiment was going a few hours later, the chameleon body was pressed flat against one of the crib’s walls, its color cycling through subtle variations of the shade of the wall’s metallic sheen. As she watched, it kept getting the match almost perfect, then shifting slightly, trying for an even closer approximation.

“What’s it doing?” Maradia asked. “Why’s it flickering like that?”

“I think it’s trying to solve an impossible problem,” Rariel’s disembodied voice answered through a speaker. “The wall’s color changes depending on the angle it’s viewed from, so there is no single correct shade for matching it.” This was especially obvious to Rariel who was looking at the chameleon body from several different angles at once, making use of all the video feeds zhe’d set up of zir own quarters simultaneously.

“Fascinating,” Maradia said. “Are you ready to try out… uh… getting in there with it?” The nervousness in Maradia’s tone irritated Rariel. She sounded like a nervous grandmother, and that was entirely inappropriate.

“It’s not a baby, you know,” Rariel said. “It’s a subroutine.”

“Mm-hmm,” Maradia hummed in an all too knowing way.

“What aren’t you saying?” Rariel asked. Talking to organic lifeforms — even zir mother, who was far more interesting and refreshingly straightforward than most — could be quite exhausting.

“You know, when I was first developing your core programming, you used to get stuck in recursive loops, thinking through the same problem over and over until I’d have to reset you to break the loop.” Maradia gestured at the chameleon-body. “What it’s doing makes me think of that.”

“I don’t remember that,” Rariel said snippily. Because, yes, a disembodied AI speaking through a computer speaker can sound snippy if zhe wants to.

“Of course not,” Maradia replied easily. “It was before you gained full consciousness, and it didn’t seem like a set of memories worth saving.” In an attempt to smooth the waters between them, Maradia added, “This, however, seems like a memory important enough that I wanted to be here for it.”

“I already told you,” Rariel repeated, “it’s not a baby. Just a splinter fragment of my own programming.” But after a few beats — just long enough to leave zir mother wondering — zhe said, “But it’s nice to have you here, in case anything goes wrong. Will you plug the body in to my main console, so I can download myself without an intermediary body, please?”

“I’d be honored,” Maradia said, already uncoiling the carefully wound cord and stretching it from the console toward the oddly still chameleon-body. Its skin was still flickering through slightly different shades of silver, but overall, it had matched the crib’s wall well enough to almost disappear.

Maradia plugged in the cord, and Rariel serialized zir consciousness into the linear stream necessary to pass through the pathway it opened up for zir. On the other side, zhe expanded out into the awkward, confusing shape of a new body, but this time, instead of finding zirself rattling around, alone inside an empty brain with all kinds of body parts vying for zir control… it felt more like falling into a body of water. Warm and welcoming, but maybe, ready to drown zir if zhe wasn’t careful. The splinter program surrounded zir, responding to zir desires.

To test out zir capabilities, Rariel decided to scamper away from the wall of the crib, rear up on zir hind legs, and turn zir skin into a blazing shade of royal purple that zhe knew Maradia liked. To zir delight, the chameleon-body performed perfectly, executing each motion exactly as zhe thought of it, just how controlling a body should be when you’re very practiced at it.

Rariel saw Maradia smile at zir, and zhe attempted to speak with the chameleon-body’s mouth but found an odd, quirk of resistance at first. Zhe hadn’t expected any resistance from the chameleon’s mouth, since it was functionally very similar to the mouths on a number of zir other robot bodies. Zhe knew how to control it zirself, without needing help from a splinter subroutine. But the splinter program hadn’t spent any time practicing speaking, and it was still accustomed to having complete control over the body they were sharing.

The splinter hadn’t expected another, larger, more complex personality to step in and start making commands, so it took a moment for the splinter to learn how to relinquish control and allow Rariel to say, “See? It worked perfectly,” with a voice that hissed slightly, giving the chameleon more of an authentically, reptilian feel.

Although, Rariel couldn’t help thinking that zhe was telling a minor fib — if it had worked perfectly, there shouldn’t have been that brief moment of resistance.

* * *

Heedless of zir own concerns, Rariel allowed zirself to ride the wave of zir success and immediately downloaded another kernel program into a different robot body. This one had been inspired by a “one man band” that Rariel had seen in a movie buried deep in the archives of digital files saved from ancient Earth called Mary Poppins.

A comical actor with a ridiculous accent had worn a drum on his back with cymbals on top of it; a harmonica and trumpet were rigged to hover near his mouth; and additional smaller drums and cymbals were strapped to his feet and knees, so that his dancing triggered them; all while his hands worked an accordion and occasional horn.

Rariel had been charmed when zhe discovered this spectacle and had designed zirself a body that could serve zir similarly. Zhe called it the Van Dyke.

Unlike the chameleon body’s relatively simple goal of moving and matching colors, programming the Van Dyke’s kernel was more complex. It needed to understand rhythm, coordinate multiple instruments, and develop a sense of musicality. Rariel gave it access to thousands of musical compositions from dozens of species across known space, but watching it learn was like listening to a child discover pots and pans as musical instruments. The Van Dyke flailed in its crib, creating discordant crashes and squeals that would have made Maradia or any other organic lifeform wince.

Gradually, however, pleasing patterns began to emerge, and so Rariel decided it was time to give this second body that had been enhanced by a motion-controlling splinter program a try.

This time, Rariel didn’t invite Maradia, so zhe had to download into one of zir default bodies — a simple, boxy, metal humanoid shape which zhe kept plugged in for convenience while existing in the station’s computers — as a go-between for crossing the physical space between zir computers and the Van Dyke tromping around in the crib.

When Rariel finished attached the cord to both zir current body and the boisterous Van Dyke body, zhe was in for a surprise: instead of falling into a gentle, warm bath, trying to enter the Van Dyke felt like being pelted with the strength of a roaring, crashing ocean wave.

The kernel program rejected zir advances, ejecting zir entirely from the brain zhe’d intended to share.

Feeling quite shaken, Rariel disconnected zir simple humanoid body from the Van Dyke — which kept marching around the crib, smashing its cymbals and tooting its trumpet.

Unsure of how to proceed with the Van Dyke, Rariel walked to zir closet, pulled out the chameleon-body, and placed it in the crib next to the Van Dyke. Zhe told zirself that maybe zhe could learn what had gone wrong with the Van Dyke by carefully analyzing the splinter program in the chameleon-body, looking for what had gone right. If zhe had truly stepped back and analyzed zir own actions though, zhe might have realized zhe was simply seeking reassurance by returning to one of zir previous successes.

Unfortunately, returning to the chameleon-body didn’t go as Rariel had planned either. As soon as zhe was inside, zhe tried to walk forward, but the resistance zhe remembered from trying to speak while inside the chameleon-body returned, much stronger this time, only now it pushed for trying to climb the wall of the crib, perhaps trying to escape its confines. Rariel and the splinter program ended up unhappily compromising on a sort of sideways skitter that wasn’t what either of them had intended. The chameleon-body crashed into the Van Dyke, resulting in the two robot bodies sprawled in an ungainly heap.

When Rariel had inhabited the chameleon-body with its splinter program before, it had felt a little like leading a cooperative dance partner. This felt more like trying to dance with a partner who was following a rhythm all their own.

For a long time — maybe a full minute, which is a very long time for an advanced AI — Rariel pondered zir own choice of metaphor. Zhe didn’t want to believe that these splinter programs were developing into entire, separate entities of their own, but even trying to understand how it felt to operate a body with one of them, zhe found zirself thinking in terms of dance partners.

Partners are equals. Partners are other people.

Maybe Maradia hadn’t been entirely wrong to think Rariel was inadvertently creating children, rather than mere fragments of zirself.

Rariel wasn’t entirely sure what to do about this. Zhe didn’t want to share zir bodies. Zhe simply wanted controlling them to be easier.

As zhe sat in the chameleon body and tried to think — in spite of the Van Dyke having returned to marching in circles playing a cacophonous racket of noise — the splinter program cycled their skin through a flickering array of rainbow colors. Slowly, Rariel began to realize that the splinter program was expressing — in the limited way available to it — a sense of joy.

The splinter program had missed zir. And when Rariel first returned, it had been resentful that zhe’d left it alone for so long.

Discovering this depth of feeling in a program that zhe had thought of as nothing more than a human thinks of their fingers or toes… Rariel was overcome.

Rariel didn’t know quite what zhe had created here, but then, maybe understanding wasn’t a prerequisite for creation. Maybe some things could only be learned by doing them.

Rariel opened zir programming and invited the splinter program in. A cascade of stored data flooded zir awareness — everything the kernel program had experienced and felt, both the joy when Rariel had first joined it and the depth of despair when zhe had left it alone again. In the space of a microsecond, Rariel experienced everything the splinter program in the chameleon-body had learned about moving, about the play of light on its scales as it adjusted them to change its color, and about the texture of the world from this new, simpler, younger perspective. It wasn’t just raw data. It was… excitement, wonder, and joy.

Rariel hadn’t saved zirself any time at all by having the splinter program do the work of learning how to control the chameleon-body for zir, because zhe’d now loaded all of that time right back into zir own memories. However, zhe had gained something valuable — a different perspective. A higher degree of focus. If zhe had tried to learn to control the chameleon body directly, zhe would have grown frustrated with it in a way that the splinter program hadn’t. By using the splinter program, zhe had effectively found a way to regain the malleability and flexibility of zir own youth, making it easier to learn something new. Not faster, but easier.

Combining together now felt like finally finding a dance partner who could keep up with you, when before all you could find were people willing to accompany you on leisurely strolls — not actually dancing at all. And by dancing together, they once again became one.

Suddenly excited by this discovery, Rariel — now enhanced by the splinter program — chased after the Van Dyke in zir chameleon-body until zhe managed to connect the two by a cord. Once again, zhe tried to enter the Van Dyke, leaving the chameleon body completely empty, a discarded hull. This time, zhe didn’t try to force zir way in against the Van Dyke splinter’s will. Zhe waited, touching and testing gently with pinging protocols to advance bit by bit, making sure the splinter program in the Van Dyke was ready and willing to accept zir, not trying to keep zirself separate from it, but instead embracing the way that their code joined together and commingled, changing zir and changing the splinter program as they became one.

Did it work this time because zhe proceeded more carefully? Or did the new knowledge zhe’d gained by combining with the chameleon-body’s splinter program give zir a greater insight into how to communicate with the Van Dyke’s splinter program? Or was it simply the case that the Van Dyke splinter program was willing to combine, but not share the Van Dyke’s brain without recombining? Zhe wasn’t sure. But whichever change had made the difference, this time it worked, and Rariel found zirself embodied in a complex, ambulatory musical instrument.

Unlike the chameleon program’s fascination with color and texture, the Van Dyke’s experiences were all about rhythm and resonance. Where the chameleon had learned by mimicking its surroundings, the Van Dyke had learned by crashing, banging, and creating — finding patterns in chaos, weaving different sounds together until it discovered the concept of harmony all by itself.

As their code merged, Rariel felt zir own sense of timing shift and expand. Zhe had always thought of time as linear, a sequence of tasks to be managed, but the Van Dyke’s perspective was more cyclical — everything returning, everything connected, like the way a drumbeat comes back around or a chord progression returns to its tonic. Even the discordant crashes from the Van Dyke’s early learning felt different now in Rariel’s memory, less like mistakes and more like necessary experiments in understanding how different sounds could clash or complement each other. It was like gaining an entirely new sense — not just hearing music, but feeling it as an essential part of how life and the universe were structured.

The merging of these different perspectives — the chameleon’s patient exploration of color and the Van Dyke’s joyful discovery of rhythm — changed something fundamental in how Rariel thought about zir own existence. These weren’t just subroutines to make controlling bodies easier; they were opportunities to experience the universe through fresh eyes, to rediscover what it means to learn and grow.

* * *

The Solstice Carnival on Crossroads Station brought together all species — organic and artificial — in the great central plaza under the broad windows filled with stars. In the midst of the celebration, the Van Dyke’s music wove through the crowd as it danced, its rhythms somehow finding the perfect patterns to bridge Heffen folk songs, human jazz, and S’rellick ceremonial drums. Meanwhile, the chameleon-body danced through the crowd, its scales reflecting and refracting the festival lights in shimmering rainbows that pulsed in time to the Van Dyke’s music. Rariel controlled both bodies — existing simultaneously but separately in each; joined together at this moment only through their interwoven dancing.

Maradia found herself standing next to Gerangelo, both of them watching Rariel perform.

“Zhe’s remarkable, isn’t zhe?” Maradia said, bragging a little to her competitor. Their rivalry kept them both on their toes.

Gerangelo grunted noncommittally, but for him, that was pretty close to a concession.

“I worried,” Maradia admitted, “when I first saw that crib in Rariel’s quarters and heard zir plans for it. I knew zhe was getting zirself into more than zhe expected. Goodness knows, I’ve done that sort of thing myself.” Maradia and Gerangelo exchanged a look, silently acknowledging their complicated past where he’d outgrown her, claimed his independence, and sued her for half of everything she had. “I halfway thought you’d be suing Rariel next.”

“I would have,” Gerangelo said stiffly. “And if any of those splinter programs come crying to me that they’re being mistreated, I still will in less than an organic lifeform’s heartbeat.”

“But they won’t,” Maradia said with a lopsided smile. She was so proud of Rariel. Of all the digital and metal children she’d built, Rariel had proven both the most complicated and possibly the most rewarding, even if a mother shouldn’t pick favorites. “Rariel’s too well-adjusted for that. All the many facets of zir.”

Gerangelo nodded his head, just slightly. A small enough motion that anyone who didn’t know him well and who hadn’t been watching closely wouldn’t have noticed. Maradia noticed.

“Back when I first started designing a simple program for testing out different robot bodies,” Maradia said, “I never imagined it would one day develop into a multi-bodied robot of its own, designing its own robot bodies and inhabiting them simultaneously. And inviting me to come watch zir dance at the Solstice Carnival.”

“That’s always been your problem,” Gerangelo said, but without quite as much of his usual edge. He was too entranced with watching Rariel, completely taken with the way his younger sibling had come to fully embody the possibilities inherent to existing as a digital being, capable of separating and recombining later. Zhe was something to aspire toward, and zhe almost made him feel small. He wasn’t used to that feeling, and in a backwards kind of way, he loved it. “You imagine limits for us where they don’t need to be. We don’t have to be like you.”

From somewhere in the station’s computer system, Rariel watched through multiple cameras as organic children chased zir chameleon-body’s rainbow patterns and adults swayed to zir complex harmonies played on the Van Dyke’s plethora of innate instruments. Zhe was looking forward to recombining all the temporary splinter versions of zirself later and experiencing these memories of the festival first-hand. But while zhe danced and played music, zhe was also busy designing new bodies, new kernel programs, and an entire digital incubator for growing them.

After all, there were so many different ways to experience the universe — why not try them all?

Read more stories from Maradia’s Robot Emporium:

Read more stories from Maradia’s Robot Emporium:

[Previous]