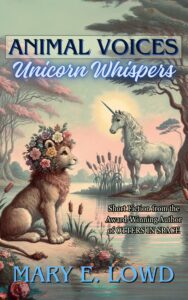

by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Animal Voices, Unicorn Whispers, October 2024

Pollen floated on the unseasonably warm spring breeze like glitter, glinting golden in the late afternoon sun. Each speck a tiny grain of hope, most to be left unfulfilled, for this pollen dispersed from a plant that didn’t belong on the mundane plains of the British countryside. It didn’t belong anywhere on Earth at all, and its root-mates had already wreaked havoc across all the great cities of Earth, leaving them empty. The cohort of carnivorous plants had been a catastrophe for humanity, but the wilder parts of the world… those hadn’t fallen prey to this pollen’s particular magic yet.

So far, only cuttings of the original plant had survived, carefully tended and transported by the very humans who became their prey, but with London laid to waste, the optimistic species of flora tried once again to spread by way of the air.

And this time, one speck of golden hope landed in exactly the right place, on exactly the right flower — a little yellow primrose that had mutated in a way that proved compatible and was now simply waiting to be fertilized. The little yellow blossom, matched with the infinitesimal yellow seed, closed up its petals and began to bulge, fruiting over the slow course of many weeks into a bulbous protrusion with a seam down its middle that served as a hinge.

The bulbous fruit — vaguely clam-shaped and speckled in variegated shades of green — hinged open in a yawn, waking up for the first time as the sun rose on the summer solstice. All around it, fiddlehead fronds uncurled, stretching out to greet the day. It was a glorious little plant — part primrose, part unearthly terror, and entirely hungry — ready to take over this backwater part of the world.

All the little hybrid plant needed now was a snack, a few tasty, meaty morsels to help it grow bigger and stronger. Once it grew big enough, it could send out runners from its roots that would grow siblings for it, and when the throng of them were all truly strong and thriving, then they could release their own pollen, now adapted to be better compatible with the plentiful primroses on these grassy downs.

Fortunately, the little plant was good at waiting. Being rooted to the ground, it didn’t have a lot of choice in the matter. What it could do was stretch out its fronds and leaves in an appealing way, hoping to look delectably edible, and sure enough, after a few days of fluttering its leaves just so and curling its fronds compellingly, a hungry rabbit came hippety-hopping along, grazing on the tender green shoots of grass.

Already well-practiced at waiting, all the little plant had to do was hold perfectly still until the rabbit — a rangy thing with fur the color of wet sawdust — cozied up close enough to take a tentative taste of one of mutated primrose’s tenderest-looking fiddlehead fronds. The nip sent a jolt of pain along the frond’s stalk all the way to the heart of the little plant, letting it know: it was time to snap!

The little hybrid primrose made quick work of the gamy sawdust-colored rabbit. Its clamshell mouth was the perfect size for eating rabbits, and since it swallowed them up whole, no traces were left behind to frighten the next rabbit away.

Over the next few weeks, the plant grew slowly larger and kept its belly full by snapping up a foolish, careless rabbit every few days. However, eventually, the word got out among the rabbits on the nearby downs that the particular glade where the hungry little mutant plant was rooted might be haunted, since rabbits kept disappearing there.

And rabbits started to stay away. Even the careless, foolish ones.

The mutant primrose began to grow hungry, and it stretched out its fronds and vines, searching for something furry to capture. The little plant didn’t have eyes, not exactly, but some of the darkest green speckles on its clamshell mouth were sensitive to light, so it could see a little. It kept hoping to see another fuzzy brown blur, but none arrived. Disappointed, since the rabbits had been so tasty, the mutant plant directed its energies towards growing little yellow primrose blooms at the end of some of its longer vines.

By holding its new blossoms up in the air, the mutant plant was able to attract hummingbird hawk-moths and some other types of insects to munch on. Capturing them was more work, since it involved keeping the yellow flowers in bloom, and insects tasted dusty and meagre compared to the meaty flesh of a rabbit. So, the mutant plant’s growth slowed down, and it had to accept that many months might pass before it would gather the energy necessary to send out runners that could grow into more clamshell mouths, or better yet, go to seed and release a new, more potent haze of golden pollen across the downs.

Then one day, a fuzzy shape approached the mutant plant, stepping hesitantly, cautiously through the dew-covered grass. This figure wasn’t sawdust brown, or mud puddle brown, or any shade of brown at all. It was startlingly white. Bright white. The mutant primrose thought it looked a little like a tiny sun and felt an immediate, irrational fondness for the fuzzy white shape.

It was an albino rabbit, and the other rabbits in her warren had teased and taunted her for her too-bright fur and blood-red eyes her entire life. She looked like a ghost or vampire to them. Something unearthly. Something haunted. So when she heard about a haunted glade where something unearthly lurked, she knew it must be where she belonged. Other rabbits may have faced horrible fates there, but she had no fear. The other rabbits had already beaten it out of her with their cruel words and cold shoulders.

The albino rabbit stared at the mutant plant with her eerie red eyes. She saw its fronds and leaves quivering, and its speckled clamshell mouth which had grown spiky protuberances like teeth all along its edges worked subtly, opening ever so slowly, too eager at the smell of rabbit on the air to hold still like it should.

“You’re unlike any plant I’ve ever seen,” the rabbit said.

“And you’re unlike any other rabbit,” the plant answered, before it could realize what a foolish idea that was. It should have stayed still. It should have stayed quiet. But the rabbit’s forthright address had startled the plant too deeply, and it was too late to turn back now. So, the plant continued and said, admiringly, “You look like a tiny cousin to the sun, come down to Earth.”

The rabbit laughed. “Kin to the sun, I like that.”

“Then I shall call you Sun’s Kin,” the plant said proudly, very pleased to have pleased such a bright, glowing creature. “Will you stay and talk with me?”

The mutant plant hadn’t realized it was lonely until now. There hadn’t been any alternative to solitude until this brave, bright rabbit had wandered up close enough to talk to and inspired an entirely new facet of the little plant’s existence. The plant didn’t want to lose this new part of itself that the rabbit drew out and quivered with fear all over at the idea of the white rabbit leaving it, once again alone but now aware of it.

Fortunately, Sun’s Kin folded her paws under her and settled down, just out of reach of the mutant plant’s grasping vines and clamshell mouth. She might be brave, but she was no fool. She would stay and talk to the plant, but she would not let it touch her. “And what shall I call you?” Sun’s Kin asked.

The mutant plant hesitated. It seemed only fair that since it had named the rabbit, the rabbit should return the favor and bestow a name — as a sort of gift — on the plant. But the rabbit wasn’t offering.

“I don’t know,” the plant answered. “No one has ever spoken to me before today.”

“A shame for them, surely,” Sun’s Kin said. “You’re so poetic. They were missing out. Perhaps I shall call you Poet Plant?”

The name ‘Poet Plant’ was perhaps not quite so poetic as ‘Sun’s Kin’, but the mutant plant was so delighted to have been gifted with a name that all its fiddlehead fronds curled up and its leaves fluttered joyously. “I am honored to be your Poet Plant,” it said, “and I will answer your shining brightness with words that open like the flowers in a garden, always turning toward and worshipping the sun.”

And so Poet Plant serenaded Sun’s Kin with lyrical soliloquies, finding that metaphors sprang to life from the tip of its leafy green tongue and words wove their way into intricate braids of idea as it spoke. Poet Plant found a purpose beyond eating, growing, and striving towards reproduction. It found meaning in conversing with Sun’s Kin and a true sense of identity in the name the kind rabbit had gifted it.

Days passed by, and the two unlikely friends fell into a comfortable rhythm. During the heat of midday, Sun’s Kin stretched out on the grass, just out of reach of Poet Plant’s grasping vines and snapping clamshell mouth, and they conversed. They talked about everything under the sun, from Sun’s Kin’s childhood in the rabbit warren to Poet Plant’s ancestral memories of worlds beyond the sky where its progenitor had originated. During the cooler times at sundown and dawn, Sun’s Kin wandered off to graze for tasty morsels of greenery, since she’d already eaten the choicest shoots and buds in an ever widening circle around Poet Plant.

At night, at first, Sun’s Kin returned to the rabbit warren to sleep somewhere safely underground, and Poet Plant did its best to capture enough hummingbird hawk-moths to soothe its hunger while Sun’s Kin was away. But as the two creatures — dissimilar in form but sympathetic at heart — grew closer together, Poet Plant found that it had to occasionally risk snapping up a tasty, plump and spicy bumblebee or other insect while Sun’s Kin was there to see. The rabbit didn’t flinch at the sight of her friend eating insects, so Poet Plant grew bolder. Furthermore, Sun’s Kin found herself staying later and later into the night, watching the stars come out, one by one, as she listened to Poet Plant’s stories of faraway worlds until one night, she found that she didn’t want to return to the warren full of unfriendly rabbits at all.

Sun’s Kin labored under no delusions. She knew that Poet Plant must be the predator who haunted this glade, and watching it snap up insects, she knew it could easily eat a rabbit with its toothy clamshell mouth. But she wasn’t afraid. She also knew: Poet Plant would not eat her. It would not risk losing its beloved audience. So finally, tired and disaffected from the latest round of teasing from her fellow rabbits, Sun’s Kin cozied right up against the carnivorous plant who had become her personal bard, singing stories to her, for only her, that filled her tall ears with music and her red eyes with dancing visions.

Poet Plant could hardly believe it at first. This bright, glowing, little cousin of the sun had curled her warm, fuzzy body against its thick green stalk, right under the chin of its clamshell mouth. Sun’s Kin side rose and fell with her breathing, a rhythm that was totally foreign to Poet Plant who didn’t need to breathe. Even so, Poet Plant sensed the vulnerability in the regular rhythm of her sleeping breaths. The fragility of a body that needs to breathe.

Sun’s Kin trusted the carnivorous plant to protect her from other, less-known predators, and Poet Plant felt so honored by the tenuous trust that it barely dared move a leaf or frond all night long for fear of interrupting that gentle rising, falling rhythm, doubled by a second, much faster, more thrumming rhythm of the rabbit’s heartbeat. Equally fragile. Equally vulnerable.

Hummingbird hawk-moths fluttered safely past Poet Plant’s clamshell mouth that night, and as dawn finally began to break, it finally risked curling a few of its vines around Sun’s Kin in a gentle, fond embrace.

After that night, Sun’s Kin always slept wrapped in Poet Plant’s vines and fronds, protected from the furry and feathered predators who might otherwise attack a rabbit foolish enough to sleep above ground at night. A few owls did try to snatch the sleeping white rabbit in their talons, but Sun’s Kin slept through their attacks undisturbed and Poet Plant learned that it had a taste for the stringy, crunchy meat and bones of owls.

Eventually, Sun’s Kin dug a small burrow beside Poet Plant, nestled among its roots, to keep her warm during the coming winter. When the winter was especially harsh, Poet Plant encouraged her to go ahead and nibble at the runners it had been trying to send out to grow itself siblings. All Poet Plant’s reproductive plans had been forestalled by its focus on Sun’s Kin anyway.

“Won’t it hurt you?” Sun’s Kin asked, shivering in the cold winter air.

“A little,” Poet Plant admitted, “but not as much as watching you suffer. Besides, I’m not sure I want copies of myself to sprout up in the spring anymore. What if they didn’t love you the way I do? What if they put you at risk?”

Sun’s Kin had never been loved or cared for by her own species in the way she was by Poet Plant. It was a strange feeling, being treated like her health and welfare mattered. She liked it, and it made her feel guilty about the idea of essentially nibbling off Poet Plant’s toes, day after day, every time it grew new ones. But the cold was bitter, sharp, and biting. It cut right through her bright, white fur when she was hungry, and so she accepted Poet Plant’s invitation.

Sun’s Kin began by tentatively nibbling only the tiniest bits of Poet Plant’s roots and extra leaves — they tasted so sweet and green! — but by the spring, the two unusual friends had fallen into a new kind of relationship. Sun’s Kin pruned Poet Plant, keeping it trim and neat, only leaving the roots and leaves it actually needed to survive alone. Everything else was fair game, and Sun’s Kin found it so much easier to live this way, she didn’t have to worry about foraging far afield.

By now, Poet Plant knew everything about Sun’s Kin’s life before they’d met and had, in turn, shared everything it knew about the world beyond the downs. Even so, the rabbit never tired of listening to the carnivorous plant spin wilder and wilder tales — clearly fictional, nearly ridiculous, but each of them delightful. In the stories Poet Plant told, Sun’s Kin explored lairs deep underground filled with lava monsters and demons; she flew across the universe in a spaceship grown from tightly woven blackberry bracken; she outsmarted gods and ascended to a throne on the surface of the moon, where she could look down on the entire world below. She lived more lives in Poet Plant’s stories than a simple rabbit could ever hope to experience in reality. She was content.

As the years passed though, Poet Plant began to wonder how long rabbits could live. It wanted to go on this way forever, but it began to see that Sun’s Kin hopped more slowly now, and sometimes, she stumbled on her long feet. Her long ears grew less sharp, and she had to ask Poet Plant to speak up or repeat parts of its stories for her.

Time passes and the wishes of rabbits and carnivorous plants can’t stop it.

So, one day, as Poet Plant stroked Sun’s Kin’s white fur — less glossy now than it used to be — with its vines, the carnivorous plant found itself counting the time between the rabbit’s breaths, worrying that its friend had slipped away and the gentle rise and fall of her furry side was over. Her breaths had gotten so weak. But Sun’s Kin awoke, lifted her head, and shook out her ears as if nothing had changed.

“I want you to eat me,” Poet Plant whispered. “Before you die. I don’t want to be left alone without you, and if you eat me, then I’ll be with you forever. We’ll die together.”

Sun’s Kin blinked her red eyes, glazed over now with cataracts. “But then who would tell me lullabies?” she asked.

“You know all my lullabies by heart.”

Sun’s Kin shook her head stubbornly. “I could have eaten you, long ago, you know,” she said. Her voice shaky and ponderous. “I thought about it. I know that you were planning to take over the downs with your runners, and all of you would have eaten my kind. All except you, maybe. But all your siblings, all your root-mates. They would have eaten the other rabbits from my warren. But I haven’t been among my own kind for a very long time.”

“You haven’t,” Poet Plant agreed. It was captivated by the rabbit’s words. Their roles had flipped, and all Poet Plant wanted was to know what else Sun’s Kin might say.

“You have to outlive me,” Sun’s Kin insisted. There was a fierceness in the rabbit’s voice, the kind of determination that can only come from age, from watching the world pass by and change, from discovering what you actually value and knowing you’re willing to fight for it. “Perhaps I should care more about my own kind, but through all of my life, the one thing that has brought me the most hope, joy, and the greatest value… has always been you. When I am gone, I don’t care if there are little rabbits hopping across the downs. I care that there are little Poet Plants, nestled among the greenery. I want to know that you finally sent out runners, that you finally released pollen, and that there’s more of you, everywhere in the world.”

Poet Plant could hardly believe the words it was hearing. It didn’t want to live without Sun’s Kin, and it didn’t care anymore about populating the world. But it did care about its best friend’s wishes.

“I will begin sending runners out at once,” Poet Plant said. “I will release pollen first thing next spring.”

“I’m glad,” Sun’s Kin said, and she closed her eyes, peacefully. She pictured the coming apocalypse for her kind, and she couldn’t be sad about it. She felt only joy at the idea of her beloved Poet Plant filling the world with its silver-tongued offspring. She fell asleep to a lullaby — a new one, improvised that very moment — about how every blade of grass, every scrap of green in the entire world, should one day sing of the tiny sun who had spent a lifetime sleeping in the roots of a grateful plant and would now rise back up to the sky, where anything as bright and shining as her truly belonged.

Read more stories from Animal Voices, Unicorn Whispers:

Read more stories from Animal Voices, Unicorn Whispers:

[Previous][Next]