by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Commander Annie and Other Adventures, November 2023

Nawry discovered the Karillow tree nestled between the bounteous persimmon and peach trees behind Aumna’s house. It was a little, silver branched waif, and, unlike all the other trees in the glade, it was winter-naked all winter long.

When Nawry asked Aumna about the incongruous little tree, she told him, “That’s a Karillow tree, and it’s an immigrant to this world too. The seed for that tree traveled as far as your people did before settling in my garden.”

Nawry knew that some seeds were carried in the fur, feathers, or bellies of birds and beasts, and he wondered what kind of animal the Karillow hitched its ride on. It must have been very brave to travel into an entirely new world all alone.

Nawry watched the Karillow closely as winter in the outside world began to thaw away. Everywhere in the bramble thicket, buds of green appeared, and tiny, hopeful shoots pushed up from the hitherto winter-empty gardens in the Noodlebeast village. They were the first hints of early-blooming noodleflowers.

And, then, the Karillow took on a green-tipped glow: a silver candelabra alight with tiny green flames. When Nawry told Aumna, she smiled and handed him a pitcher. “Water it for me,” she said, but the pitcher wasn’t filled with water.

Nawry swirled the pitcher and sniffed its contents. The white liquid inside smelled organic, and it lost a little of its opacity around the edges of its teapot-sized whirlpool.

“What is it?” Nawry asked, wrinkling his whiskered nose.

“Milk,” Aumna said. “My visitors bring it to me from the village, and while the Karillow tree does alright with water, it likes milk better.” She smiled bemusedly at Nawry, watching his whiskers swell in and out with the investigatory snuffles of his nose. “Try it if you like,” she said.

He looked at her uncertainly, then brought the pitcher to his jowly lips. Milk froth caught in his whiskers, and he had to brush it away. The taste was strange; he wondered if his mother could make a pasta sauce from it. He’d have to get her some from the village someday.

“Make sure you pour it all the way around the trunk,” Aumna said. “And splash a little on the new buds too.”

Nawry watered the Karillow with milk faithfully and daily from then on. Aumna had the pitcher waiting for him every afternoon when he arrived. She looked expectant when Nawry took it and questioning when he returned, empty pitcher in hand. But she never directly asked her question. She didn’t have to. It was obvious the day that the answer became yes.

Nawry took the pitcher around the back of the house; he was planning a way to tell Aumna he might not visit again for a while. The other young Noodlebeasts had started some waterball teams, and he knew he swam better and held his breath longer than the lot of them. But they wouldn’t let him join unless he promised to be around more often. They didn’t want to shuffle the teams around all the time to fit him in.

Thoughts of waterball were pushed right out of Nawry’s head when he rounded the corner of the house and saw the Karillow. The buds had opened, and the leaves had untwisted. It was resplendent in emerald and celadon whorls, completely contrasting the orange shades of the rest of Aumna’s glade, but that wasn’t what stopped Nawry still in his tracks.

As the buds had been growing incrementally toward their new, open state, Nawry had been able to see the touch of silver-gray, fuzzy-tipped seeds poking out from inside them. He expected to find the seeds fallen from the open buds, scattered about the Karillow’s trunk and roots. And they were. But, they didn’t lie there, discarded, helplessly waiting for the wind or a hungry animal to carry them away.

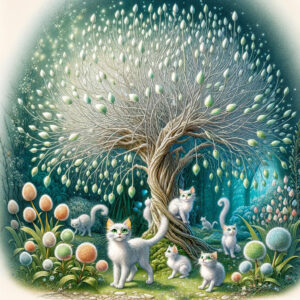

They didn’t need any animals to carry them away. The seeds could carry themselves away, on their own four, tiny feet. The seeds, as they were, looked vaguely feline — miniscule, cuddly, and fuzzy — with fluffy puffs of tails and Cheshire faces.

Freed from the buds that had held them, the silver-furred Karillow seeds flitted and chased each other all about the tree’s limbs. Some stretched out on the green pedestals of leaves; others had flocked to the ground. Their antics down there, at the base of their tree, suggested a midsummer picnic, replete with races and treasure hunts; or, maybe, an outdoor school in full session.

Nawry wasn’t sure whether to water the Karillow or not. It seemed impolite, if not downright violent, to pour a pitcher’s worth of milk on the tiny beings. He rocked back and forth on his flippered feet while weighing his options, but he wasn’t careful with the pitcher. A tablespoon’s full of milk sloshed over the side. Nawry froze, mirroring the actions of the dozen or so seed-beasts drenched in milk.

“Milk!” they began to cry, their tiny voices mewing. Soon all the other seeds joined them, and a great chorus of chirping voices assailed Nawry. He was almost too shocked to do what they wanted, but that didn’t last long.

The seed-cats jumped and rolled and arched their backs, basking in the pouring milk. When all the pitcher’s-worth had been poured, they set about washing themselves, licking their paws and rubbing their whiskery faces, seemingly quite content.

Nawry watched them for many minutes before daring to tear his eyes away. He could hardly contain his burbling, enthusiastic descriptions of the miniature kittens long enough to make it back to Aumna.

“So they’re finally bloomed,” Aumna said after Nawry finished his exuberant exposition.

“Finally?” Nawry asked, realizing he hadn’t had to describe the seed-cats to her at all. “You knew about them…”

“That tree came to me as a tiny, weary seed eight years ago,” Aumna answered. “I showed it that place between the peach and persimmon, and by the next year, the seed was a foot tall sapling.”

Nawry tried to picture one of those delicate, miniscule, kitteny seeds making the long journey his own people had made. Such a seed must not have been only very brave but also very strong.

“It started blooming two years ago,” Aumna continued, “so this is the third summer I’ll have a little civilization outside my back window.”

“Do they die every year?”

“Yes,” Aumna answered gravely. Although, her gravity seemed more concerned with how Nawry would take the news than with the news itself. She knew the ways of the Karillow and had made her peace with it.

“Do any of them grow into new Karillow trees?” Nawry asked, seeking a glimmer of redemption for the playful, little creatures’ short lives.

Unfortunately, Aumna told him, “None yet.”

Nawry carried the yet with him for the rest of the day, as he lay in Aumna’s back garden, watching the kit-seeds work and play.

It was an entire, miniature civilization, replete with social hierarchies, political intrigue, and an active art scene. The kit-seeds absorbed the basics of language directly from the mother tree while still budding. The rest of their education came from studying the records studiously scratched by previous generations into the mother tree’s bark.

So far as Nawry could tell, all of Karillow arts and literature were carved into the mother tree’s bark by tiny kit-seed claws. The oldest records, of course, ringed around the bottom of the tiny tree’s trunk where many of the kit-seeds held court, reading the scratchings of the past years and learning what kit-seeds-gone had known.

New writings and line-murals were added to the higher, fresh branches — but sparingly, for the Karillow’s crown was a hot-bed of ascensions and back-stabbings. Since the tree’s crown was, clearly, the most highly prized real-estate in the entire Karillow civilization, it faced constant turn-over. A kit-seed who perched proudly on the very highest open-bud hadn’t the time to gather her thoughts well-enough to begin carving them in the untouched bark beside her. Every moment had to be devoted to guarding her ground, fiercely, with extended claws and slashing paws, turning other ambitious kit-seeds away.

Of course, no kit-seed held such a high-perch for long. And Kassy — though she held it the longest of any kit-seed Nawry watched that day — soon found herself thrown from the heights of her mother Karillow tree. She landed on the ground, hissing and spitting, not far from Nawry’s webbed left paw. He pulled his foot backward quickly, wary of the tiny danger nearing it.

Kassy’s eyes followed his paw backward, traced the path of his furry leg to his bulky body and on upward, until her fearsome gaze came to meet Nawry’s inquisitive one. “I wouldn’t claw you,” she said. Her voice, small but clear and piercing, carried all the way up to Nawry’s bearded ears. “You’re a giant.”

Nawry put his forepaw out toward the sassy kit-seed, making his web-fingered hand into a slightly cupped and inviting platform for her.

Kassy gingerly took to his hand, testing her footing with needle-tipped claws. She walked the perimeter, hopping from finger to finger over the webbed parts, and finally settled in Nawry’s palm. The trust offered and returned — a tender palm rendered to the mercy of small but ferocious claws; and a tiny body placed in the clutches of a potentially crushing hand — may have been minor, but the effect filled both Noodlebeast and kit-seed with pervasive warmth. They were instantly fast friends, a deal clinched by the hours of conversation that immediately followed.

“What did you want to write? At the top of the tree?” Nawry asked.

“That’s not the point!” Kassy fluffed her silver fur in anger, an emotion and physical gesture that passed over and through her often. Despite her protest, Kassy realized as her anger passed that, of course, that exactly was the point. “I don’t know,” she admitted.

“You could read the writings from the bottom of the tree.”

“All the other kit-seeds are doing that.” Kassy preened her whiskers dismissively, thinking. “But they aren’t talking to you!” Her fur fluffed again, and she was so excited she stood on her tippiest toes, arching her back, and walking in a tiny circle. “Take me back to your people,” Kassy said. “If I find out about you and your kind, I’ll know something none of the other kit-seeds know about, and that will be worth writing.”

Kassy went everywhere with Nawry through the following weeks. When he played waterball with the other young Noodlebeasts, Kassy perched in the hollow of his ear. When he sat at Aumna’s table, listening to her and her guests, Kassy reigned from the corner, lapping milk from a thimble. And when the Noodlebeasts gathered at night to eat their noodly meals and sing their glorious, bassoon-like songs, she nestled in a comfy bed of springy, plain pasta, safe in a bowl on Nawry’s left knee. The bowl on his right would be awash in oils and herbs, but the pasta in the left bowl stayed as fresh as it had been on the stem — though softer and warmer — to keep Kassy’s silver fur clean.

As Kassy studied the Noodlebeasts, she became particularly entranced by the story of their long journey to the Rocky Shores. “Why did they travel so far?” Kassy asked Nawry. “Was there something wrong with where you used to live?”

“I don’t know,” Nawry answered. “I barely remember it. There was something… different. I tried to capture it in my paintings for a while. Aunt Jeminee still tries.”

“So strange. To be driven far away… and still drawn back.” Kassy’s tiny eyes looked dreamy in the firelight.

After a while, Nawry said, “I don’t think she’d be drawn back if there wasn’t something wrong here. Something that should be here. Something missing.”

Kassy had lived such a short life. Even Nawry, a mere whipper-snapper of a Noodlebeast, could see the limitedness of her life. A few weeks; a small patch of shoreline and forest. That was all she knew. How could she possibly understand the shifty, gaping wrongness that held Jeminee and the other adults who let themselves dwell upon it in its thrall? Nawry didn’t understand. Even though he remembered, and he could see the holes in this world where that something was supposed to be — he still didn’t understand.

“Well,” Kassy said, with the simplicity of extreme youth, “let’s find it.”

With the complexity of a lesser youth, Nawry hesitated before answering, “I suppose we could ask Aumna about it.” She was the smartest person he knew.

Aumna listened as they explained the dilemma. At least, Nawry assumed she listened. It was polite, and he knew Aumna to be polite. But until they finished, and even then, Aumna showed no signs of paying attention. She moved about her small kitchen, fixing drinks, watering houseplants, tidying the cupboards — anything but sitting at the table and looking at either of her vastly younger visitors. For the first time, Aumna looked old to Nawry. And not old like timeless wisdom, but old like a tired woman.

“Will you look at the farfalle?” Nawry asked, holding out the pendant from his neck. “I brought a painting, a small one, that my aunt tried to make of the farfalle in bloom…”

Aumna’s hands were squared on the countertop, her back angled toward them. Nawry saw a strand of her auburn hair fall toward her face.

“…if you think that would help,” he stumbled.

Aumna brushed the hair away, sighed, and turned toward her tryingly youthful guests. “Let me see,” she said, reaching her hand to hold the dried pendant briefly, turning it first one way then the other before dropping it back to Nawry’s thickly furred chest. She put her hand out for the painting, and Nawry unrolled it for her.

As she looked at the painting, Nawry thought he saw a flicker in her eye — some emotion that didn’t match the rest of her feelings; an emotion she quickly brushed away.

“Presumptuous,” she muttered, seating herself wearily at her own chair. She looked Nawry in the eye, and that flicker was entirely gone. “You move to a new world, and you’re surprised to find something missing?” she said. “Guess what it is. Guess what it is!”

“I don’t know,” Nawry mumbled, but Kassy played along, “What? What is it?”

“The old world.”

There was silence for a long time. At either end of the table sat a feeling of betrayal. Aumna’s sarcasm seemed completely out of proportion to Nawry. He’d always been free to express himself at Aumna’s table, and even if he’d merely been describing the silly rules to a Noodlebeast children’s game, she’d always been interested, solicitous, and most of all, respectful.

Now, when he came to her with a real dilemma, she shut him down. “It’s more than that,” Nawry persisted, quietly feeling like an idiot.

He placed the unrolled painting on the table between them and spread his flippered hands over the corners to keep it open. Aumna’s eyes flicked to the painting. Once, twice, but only briefly.

“Put it away,” Aumna said, reaching one hand to help him and another to shield her eyes. “Such a headache.”

Nawry re-rolled the painting and tucked it away. Aumna looked at him from under the shielding hand. “How dare you question the very foundation of my world?” she asked.

Nawry felt a tingle in the roots of his fur. Now she was taking him seriously, and apparently, his question was more serious than he thought. Anything that could make all the adults in his village sad and Aumna — serene, tranquil Aumna — furiously mad must be terribly important.

“Not that it hasn’t been questioned before…” Aumna seemed to be speaking to herself, and she rose as she spoke, turning away again. “Benter,” she said, the word filled with disgust and accusation. “I thought I could be finished with him.” She straightened herself, and her auburn hair caught the light from the window. It glowed orange in the afternoon sunlight.

“I can’t help you,” she said.

Nawry slumped against the table in disappointment, and Kassy spat through her whiskers. “I don’t believe you!” she hissed.

Aumna looked at the kit-seed, a mere speck of life compared to her size and years. Kassy looked away, realizing that Aumna hadn’t finished.

“I can’t help you,” she repeated. “But I’ve heard words very like yours before. At the time, I thought they were an excuse. A pathetic, paltry excuse.” Her left hand clenched at her side, twisting the vermilion pleats of her calico dress.

Nawry and Kassy waited, watching Aumna as her features betrayed the travail she was experiencing, passing through histories and memories they knew nothing of. When the journey ended, Aumna sat herself back in her chair. Weary and sighing, she said, “Neither of you is making excuses.”

Both youths, kit-seed and Noodlebeast, shook their heads.

Aumna’s lips formed a dim smile. “Neither of you has anything to make excuses for.” She waited another moment, reconsidering the decision she’d already made. “I can’t help you. The person you want to talk to is my… uncle. Benter.”

Aumna took a piece of parchment and a quill from a cupboard by the front door. “I’ll draw you a map,” she said. “But you’ll need to be very good at swimming.” She looked archly at Nawry. She knew he was. The map she sketched showed her house, the Rocky Shore with the Noodlebeast village, and then it extended South and out to sea. “Benter told me that if I ever came to visit him, I’d have to make it all the way to here–” she placed her finger on the map, far out in the sea, “–before the boundaries of his kingdom would protect me.”

“What does that mean?” Nawry asked.

“Benter is the King of the Sea. In his kingdom, it doesn’t matter if you live on the land or in the water. Everyone is protected. Everyone can breathe.”

Kassy looked at Nawry. He wasn’t sure if she looked relieved by the news that she could breathe in Benter’s kingdom or horrified that she wouldn’t be able to breathe until she got there. “I know how to search out underwater air bubbles,” Nawry said. “There are aquatic plants that make them, and the air sticks in my beard for a while between plants.”

“A while?” Kassy squeaked, her voice — unusually — as tiny as her self.

“I’ll waterproof the map for you,” Aumna told them, “so you can take it along.” She took a glass pot topped with a black stopper from the same cupboard by the door. There was a clear lacquer inside, and Aumna slathered it over the parchment. She fanned her hands over the newly shiny map to help it dry.

“You’ll need more than a few breaths from bubble-coral to make it to Benter,” Aumna said, still fanning the map. “But there are caves, here–” She pointed to the map. “–here, and here. I’ve marked them for you.”

“Caves?” Kassy asked.

“Air caves. Benter had his subjects make them, so that people like me…” Aumna paused. “…like my sister… could come visit him.”

“He won’t mind us using them?”

“It’s what they’re for,” Aumna told Kassy; then turning to Nawry, “Besides, no matter how good you are at swimming, this is a three day journey. You’ll need those caves to stop and sleep.”

Nawry had become very quiet. He’d never traveled that far from his village before. He’d never been that far from his people. His parents. His aunt. “This Benter,” he said. “He’ll know what’s missing?”

“Benter is one of only three people in this world older than me.”

Kassy looked to Nawry, but he was as surprised as her. Aumna didn’t look unspeakably old. Middle-aged, certainly. But this was the first that either of her young visitors realized they’d been visiting the home of a goddess.

“You wouldn’t be able to get to my mother,” Aumna said. “Even I haven’t seen her in years.” She said years, but meant centuries. A look of depth, ages passed and passing, appeared in Aumna’s eyes. “…many years.” She came back to them and said, “My father wouldn’t have much sympathy for your cause. So, it has to be Benter.”

Nawry reached out to the map and took it delicately in his flippered hands. He put a webbed finger over the sketch of his home and traced his way to Benter’s kingdom.

“If you’re right, and there’s something missing…” Aumna said, reaching her smooth hand to touch the pendant around Nawry’s neck. “Benter will know about it. If he doesn’t, he’ll find out for you. Puzzles — the nature of the world — that’s where his interest lies.” Aumna pulled her hand away, suddenly, as if the farfalle burned her fingers. “Ask Benter,” she said.

Then looking at Nawry and seeing the concern in his eyes, Aumna changed her tone. “It isn’t that long of a journey,” she said. “Not really. If you swim fast, you’ll be back in a week.”

“If we go to a foreign kingdom under the sea,” Kassy said, “then I will have something worth writing about. The other kits will have to give bark space to me!”

Kassy’s certainty of a glorious return to her mother tree was more comforting to Nawry than Aumna’s comforting words. Together, it was enough to stay him, ready him to accept his impending journey. He put his flipper out for Kassy, who scampered up his arm to her perch in his ear. Then, taking the map, he turned to Aumna, thanked her, and turned to leave.

On the long walk back, Nawry discussed with Kassy what they would need for their journey and how they would keep her breathing through the long swim. But he was really thinking about what to tell his parents, friends, and aunt.

Yet when the time came at the nightly bonfire to tell them of his journey, none of the words felt very important. What he remembered when they set off the next morning was the feel of his mother’s arms, the pat on his shoulder from his father, the way he felt older than all the other young Noodlebeasts, and how his aunt looked at him. She was the only one who really understood why he was going.

For the rest of them, he was just a young boy going off on an adventure. His parents were indulgent; the other youngsters jealous. But Aunt Jeminee looked almost… grateful. She was hungry for what Nawry meant to find, and it made him determined to find it.

The next morning, Nawry stood with his mother at the edge of the water, waves lapping softly at their feet. The rest of the village was still waking behind them. “Take this,” his mother said, looping the leather handle of a satchel packed with food over Nawry’s shoulder.

“Thanks,” Nawry told her. “I’ll be back soon.”

His mother smiled, as if to say she believed him with her mind but not her heart. “Yes, come back soon,” she said.

Her words echoed in Nawry’s watery ears as he swam that day. The water rushed past him, enclosing him in its dim, cool, blue world. The pressure of the water sliding over his limbs as he swam made everything feel close. His own heartbeat, his memories — everything internal was magnified.

It was like he was swimming out of time.

Within the flow of time, though, his swimming was interrupted every hour or so by the necessity of finding fresh air-kelp. He was too deep to return to the surface.

Kassy’s air supply stayed protected deep inside the smooth, calcerous twists of a giant conch shell they’d found the night before. As long as Nawry was careful not to repeatedly flip it, the air wouldn’t work its way out while he swam. He kept the conch pressed against his chest, strapped under the vest he wore, so it stayed level, and Kassy’s air stayed safe.

At every patch of air-kelp, Nawry took the shell from his vest and swooped it — carefully, ever so carefully — over the air bubbles, replenishing Kassy’s supply. But they couldn’t talk. She stayed hidden, deep within the folds of the shell, leaving him profoundly isolated in the silent embrace of the sea.

When Nawry found the first air cave on Aumna’s map — marked by a dim light that stood as a beacon in the omni-darkness of the ocean floor — Nawry barely stayed awake long enough to eat a meal of dry pasta from his pack. Before he’d even finished chewing, he dropped straight to sleep on the damp, cramped floor.

Kassy, released from her calcerous prison, was eager to talk and prattled at him anyway, but her grand monologues and deep thoughts reached only unhearing ears. The nearly-meditative quality of Nawry’s travel remained unbroken.

By the next night, at the second air cave, Kassy knew the drill, or else, two days of isolation in the confines of the conch shell had taken their toll. The companions ate silently, as silently as the echoing cave allowed.

Despite the miles of cold, dark sea above and around them, muffling every sound as Nawry swam, the cave was loud with small noises. Drips from the ceiling, the crunch of their pasta dinner, and even Nawry’s breathing filled their ears. Meaningless, white sound. It lulled Nawry to sleep again.

The third day passed in a trance. The cold of the ocean competed with the heat of exercise. Everything had fallen into a mesmerizing rhythm. That night, in the final air cave, however, Nawry broke the spell.

“We’ll reach Benter’s Kingdom tomorrow.” His words sounded strange and halting. He’d gone looking for something, and so far, all he’d done was leave everything else behind.

“Should we make a plan?” Kassy asked.

“How can we plan? We don’t know what we’re approaching…” The enormity of their journey threatened to swallow Nawry whole, or else chase him back home, like a scared little bunny running in the dark. “I’m not sure even Aumna knows.” He rolled out the lacquered map and touched a flipper tip to the drawing of the kingdom they approached. “It sounded like she’d never been there.” He put the map away.

Kassy knew no fear. The world was too new to her for their journey to fall uncomfortably outside the pattern of her life. Her life had no pattern yet, and she took each experience as it came to her.

So, Kassy spent the night whispering in Nawry’s ear — plan after plan, each less likely to have any bearing on the reality of the morrow than the last. Yet, Nawry fell asleep comforted.

Continue on to Chapter 3…

Read more stories from Commander Annie and Other Adventures:

Read more stories from Commander Annie and Other Adventures:

[Previous]