by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Typerwriter Emergencies, December 2017

Olea started screaming first, whiskers quivering with rage. She was an otter and should have enjoyed tumbling and playing all day. But she was also an adult, and Shaun was a toddler. No force on Earth or in space could keep pace with a toddler otter — except for another toddler otter, but Shaun was a rare litter of one. No sibling playmates.

All Olea wanted was to flop down, drape her long spine over the couch, and watch some TV show with fast-talking cats and dogs in suits throwing quips at each other. But as soon as she grabbed the remote, Shaun pointed at the TV and chirped in his high-pitched squeak, “Cho-bolos!” over and over — whatever that meant. Why couldn’t the doggarned kid learn to speak? Humans hadn’t uplifted otters a hundred years ago so they could chirp nonsense words. Language. It was the whole point of being uplifted.

Shaun kept chirping “Cho-bolos,” his squeaky voice growing more and more urgent. Olea knew that if she didn’t turn on some brain-melting episode of neon cartoon tripe with songs about sharing, Shaun would start screaming.

And she couldn’t take it anymore.

So she beat him to the punch — Olea started screaming. Then Shaun screamed back. The two otters — adult and toddler — squared off, screaming in each other’s faces, large round noses nearly pressed together, whiskers quivering.

All Olea had wanted was to hear some adults talking to each other, using real words, saying clever things. It was a dumb reason to yell at a toddler. Olea was fighting with a child, and she was the idiot throwing a tantrum.

Shaun was just — rightfully — objecting to his mother turning into a psycho otter before his eyes. How do you get out of that? What do you do when you’ve lost it so bad that your toddler has the moral high ground?

Shaun’s father, Dover, wouldn’t be home for hours, and Olea’s littermates and parents all lived on the space station. She hadn’t had time yet to make friends with the squirrels down here in Tree Town. She was still hoping that Dover would get transferred back to Deep Sky Anchor. Though, he was such a successful liaison to the squirrels, that was looking less and less likely. She didn’t know how he managed it; the squirrels’ jittery movements always made her nervous, and she hated nut-based food.

Olea knew that she and Shaun needed to get out of the apartment. They’d been cooped up in that little space too long. So, she grabbed his little body around the long middle and held his arms down tight while he wiggled and screamed. With enough maneuvering, she got the slippery otter babe strapped to her back in a carrier. As soon as the last buckle latched into place, she felt his body relax. Of course now her body was carrying the weight of an entire extra person. Hadn’t this all started because she was tired?

Olea trudged, one paw in front of the other, out of the apartment and down the winding, narrow staircase that circled the outside of the tree-like building she lived in these days. The ground floor of the building housed a bakery, and Olea stopped to stare through the glass windows. Squirrels buzzed about inside, ordering baked goods from the honeycomb of cubby-shelves housing them. Olea thought about going in and buying a treat for her and Shaun, but everything she saw involved nuts — almond macaroons, hazelnut-stuffed croissants, walnut pudding, sunflower seed cookies. Not a single crab cake or clam chew.

Her own reflection in the glass caught Olea’s eye. Shaun was peeking over her shoulder from the backpack. She stood staring at the reflection of his sweet brown bewildered eyes. Why was his mamma just standing here? she could see him wondering. Then the little devil caught sight of her reflection staring at him and gave her the sweetest little lopsided smile.

What do you do when your jail cell is also the only thing that makes life worthwhile? Olea wondered. It was hard to believe the world had ever seemed to have purpose or happiness before she and Dover had Shaun. Yet she’d have given anything to just dump the little otter at a table in that cafe, buy him a sticky bun, and abandon him among the squirrels.

Olea got her paws moving again and padded her way along the twisty cobblestone streets of Tree Town, listening to the sound of squirrels traversing the rickety ladder walkways above her. None of them would fall on her. She knew that, but she still flinched whenever one of them passed directly overhead. Why did everything here have to be so vertical? If she’d been on Deep Sky Anchor, she could have jumped in the central river and swum to her destination. So much easier. So much more relaxing. Instead, her paws were sore by the time they got to the nearest park.

The autumn sun gleamed on the silver branches of the artificial climbing trees and other play structures. As soon as Olea unstrapped Shaun from her back, he scampered across the grass and dried leaves to the tallest slide in the playground.

Maybe if he got his energy out, things would be better. Although, he wasn’t the one who’d started throwing tantrums, and somehow, Olea still wasn’t watching fast-talking, suit-wearing felines trade quips and catty remarks with each other while solving crimes.

She sat down on a concrete ledge near a couple of squirrel moms, but she couldn’t bring herself to talk to them. In fact, she could barely keep from snapping sarcastically at them. The squirrels kept saying things like, “Allisyn says she thinks adults should just sit down and talk things out over a bowl of candied nuts when they get mad, because candied nuts make everyone happy. Isn’t that sweet?” and “Oh my gosh! Kits are so wise! That’s exactly what I do with my litter when they get argumentative — sit them down with a bowl of candied nuts!”

They wouldn’t have understood Olea’s problems, and she could barely stand listening to theirs. It was a relief when the squirrels packed up their litters and moved on, even if it did leave Shaun alone on the playground.

Once the little otter was the only pup on the playground, the shining metal equipment lost its appeal, and he started wandering around the edges of the play area, looking for sticks, poking at the dry leaves, and pulling up blades of grass.

Shaun bounced back to his mother and presented her with a smooth, dark chestnut. He proudly proclaimed, “Cho-bolo!”, the same nonsense word she hadn’t understood earlier. She still didn’t understand it.

“That’s a chestnut,” Olea said, handing it back to him. “Squirrel scientists had to genetically redesign chestnut trees to grow here. There’s an old squirrel fairy tale about how chestnuts grant wishes. My mum used to tell it to me when I was a pup.”

Shaun grinned widely and said, “Yeah!” Then he ran off to collect more of them.

Olea was still sitting on the concrete ledge, rudder-tail going numb, next to a growing pile of chestnuts, when Dover finally texted her phone to say he was on his way home.

They’d been at the park for hours. She’d watched families of squirrels come and go, ignoring the fish-out-of-water pair of waterdogs. “Come on, Munchkin,” Olea called to Shaun. “It’s time to go home.”

At home, there would be dinner to make, bedtime rituals, and laundry to start — loads of fast-drying clothes that never got wet anymore except when they were washed. By the time it was all done, Olea would be too tired to watch some cat-and-dog buddy show. The fight had been drained out of her, sitting in the park for hours, drying up like a jellyfish on the sand. She felt sad thinking about the days stretching out in front of her — each day filled with precious but mind-numbing hours of watching Shaun play, taking Shaun to places he wanted to go, and never having time for anything as simple and stupid as watching a TV show without neon dinosaurs, something that didn’t use to be a luxury.

Olea loved Shaun, but he made her feel so trapped she could cry.

Shaun was her world. His smile was the center of the universe.

Olea picked up one of the chestnuts, felt its smoothness against her paw pads, and tried to imagine what she could wish for to make her life better, but all she could picture was blankness. No matter how hard she wished, her family on Deep Sky Anchor wouldn’t move Earth-side just for her, and she couldn’t wish away a job that Dover loved so much. She loved Shaun, but she didn’t think she could handle having a second litter. Olea wasn’t even sure her life would be better when Shaun was older. Once these precious moments that were tearing her apart had all passed… then she would miss these days. Every older otter told her so, and she knew in her gut they were right. Olea already missed the fuzzy baby, warm and snuggly, sleeping in her arms. Sometimes she hated Shaun for growing up even this much, becoming a gangly toddler otter instead of a fuzzy baby one. The loss of the baby was a knife to her heart and an ache in her arms.

And someday, Olea knew she would miss the rambunctious toddler just as fiercely. Every moment with Shaun was a grain of sand, falling away forever while scratching her in the eye, despite three layers of eyelids.

Olea squeezed the chestnut in her paw, wishing for a wish; wishing for a vision of happiness that she knew how to live with; finally, wishing that the whole world were unmade — if it had never existed, if otters had never been uplifted, she would never feel this way. Everyone would be free.

If the chestnut were a button she could have pushed to end the world — or at least undo a hundred years of evolution — she would have pushed that button.

But it was just a chestnut. And she was an otter who needed to take her toddler home.

Olea wrestled her tired, slippery little otter, against his protestations, back into the carrier on her back. And she went home to face the hours of the evening until she passed out, exhausted in front of the TV. Tomorrow, she’d find a way to do it all again. There was no other choice, and no amount of chestnut wishes would help her.

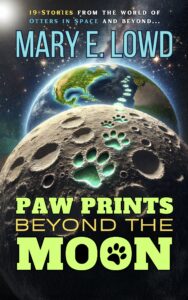

Read more stories from Paw Prints Beyond the Moon:

Read more stories from Paw Prints Beyond the Moon:

[Previous][Next]