by Mary E. lowd

Originally published in Lost In Time, October 2019

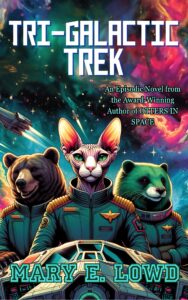

The starship Initiative glided through space, the technological culmination of centuries of work done by uplifted cats and dogs from Earth. The graceful, swooping lines of the ship’s exterior twinkled with light from within, where the ship’s crew lived their lives. Dogs and cats worked side by side, exploring the universe, searching out other species, and seeking the humans who had left them behind.

Captain Pierre Jacques was a Sphynx cat, and he was grateful from the tips of his pink ears down to the end of his hairless tail that humans had taken the time to uplift his people to sentience before disappearing from the history records. But personally, he couldn’t have cared less what had happened to them afterward. He was a forward looking cat. An explorer. That’s why he’d abandoned his degree in archeology and focused on his career in the Tri-Galactic Navy. He was one of the first feline starship captains, and he had to live up to the honor of commanding the flagship of the fleet.

A beautiful blue sphere hung on the Initiative’s viewscreen like an ornament, a glass bauble to be admired. The blue expanses of the alien world were dotted with emerald chains of islands and frosted with lacy white clouds. Captain Jacques could have stared at the world in peaceful contentment for hours, watching the lacy clouds chase each other, drifting slowly over the oceans and obscuring the island chains. But the Initiative was orbiting this world because they’d received a distress call.

“Open a channel down to the planet,” Captain Jacques ordered. He leaned against the side of his captain’s chair, and the tip of his hairless tail twitched anxiously beside his carefully crossed hind paws.

The Ursine exchange officer at the ship’s helm said, “Yes, Captain,” in her deep, rumbly voice, and with a large, brown-furred paw, she worked the brightly colored buttons on her console.

The image of the blue world disappeared from the main viewscreen and was replaced by the image of a white-furred creature with a round face, long ears, and a very twitchy nose. The creature wore a hooded robe with the hood loose around her shoulders. She looked a great deal like an Earth rabbit would, if humans had uplifted them. Much like how the Ursine exchange officer, Grawf, looked a good deal like an Earth bear.

Captain Jacques stood up from his chair and took several steps toward the main viewscreen. His tail swung jauntily behind him, and he said, “I am Captain Pierre Jacques of the Tri-Galactic Navy Starship Initiative. My crew and I have come to your world in answer to a distress call. May we be of service? What is the nature of your planet’s distress?”

The rabbit-like figure twitched her nose again, and her left ear bent in the middle, flopping forward. “You are on a starship?” she asked. More nose twitches. “Orbiting our world?”

“Yes,” Captain Jacques said, a purr rumbling deep in his throat. There was something deeply satisfying about making first contact with a new alien species. Scans of the world below had shown that this world did have space-faring technology, but the lack of satellites and outposts in the rest of the star-system suggested that they hadn’t had it for very long.

“The Tri-Galactic Navy is a peaceful, exploration-focused fleet of scientists and diplomats,” Captain Jacques explained to the alien bunny. “We’ve been exploring the three galaxies clustered together in this quadrant of space, and sentient creatures from many worlds have joined our union.” Here the Sphynx cat captain gestured with a pink-skinned paw at Grawf, the Ursine exchange officer. “We have rules for our interactions with less technologically developed species, but our scans suggest that your world has developed the basics of spaceflight. And if it’s within our abilities, we’d like to assist with whatever problem you’re facing.”

The rabbit alien muttered something, presumably to someone standing just outside the view of the screen. Then she turned back toward the captain and said, “I am Kytha of the planet Hoppalong. Our technology is the problem. We have a fleet of our own — starships, as you say — but they’ve broken down, and we need to fix them. Soon. Quickly. Right away.”

Captain Jacques glanced toward the back of the bridge and skewed an ear interrogatively at his head engineer, Lieutenant Jordan LeGuin, an orange tabby wearing techno-focal goggles. The orange tabby nodded, and then Captain Jacques turned to face the alien rabbit again. “I’d be happy to send a team down to look at your vessels, to see if we can help. In return, would you be willing to send a delegation of your leaders up to my vessel? To learn about the Tri-Galactic Union and discuss whether your planet, Hoppalong, would like to join?”

The rabbit’s other ear flopped forward, and after a moment’s consideration, she nodded. “Yes, that would be acceptable.”

Once they’d agreed on the logistics of both missions — the diplomatic summit and the technological aide — Captain Jacques ordered the communications channel closed. As soon as the Hoppalong’s face was replaced on the view screen with her peaceful blue world, Grawf rumbled from her station at the helm, “Captain, you should know that I’m getting some weird gravitational readings from the surrounding space.”

Captain Jacques approached the helm and looked at the console. The display showed the gravitational lines around the planet Hoppalong, depicted in a cheerful shade of orange. As Grawf had said, there was an unusual fluctuation, almost a pulse or a flicker, in the lines, as if there were another highly massive object nearby, distorting the gravity field.

“It almost looks like the pattern we’d see if Hoppalong had a small moon…” Captain Jacques traced the lines on the console with a carefully extended claw. “…except only if that moon were somehow popping in and out of existence.”

“Our scanners may be malfunctioning,” Grawf said, shifting her weight uncomfortably in her small chair. The bear was larger than even the biggest dog in the Tri-Galactic Navy, and so many of the fixtures aboard the Initiative seemed a little tight for her.

As a cat in a command track that had been mostly dominated by dogs before him, Captain Jacques knew what it felt like to have everything feel like it didn’t fit quite right. He’d have to see what he could do about making better accommodations for his one Ursine officer.

“Run an internal diagnostic on the scanners,” Captain Jacques said. “However, once you have the diagnostic running. I would like you to join me and the other ranking officers in the diplomatic union with the Hoppalongs.”

“Really?” Grawf said, sounding surprised. She adjusted the chainmail sash that she wore over her Tri-Galactic Navy uniform, a cultural signifier of her people.

“Yes,” Captain Jacques affirmed. “As an exchange officer, I think your insights into the benefits and process of joining the Tri-Galactic Union could be invaluable.”

“I will not let you down,” Grawf rumbled.

“I don’t expect that you would,” Captain Jacques quipped, swinging his tail jauntily again. He did enjoy meeting new societies!

* * *

Lieutenant Jordan LeGuin had seen the planet Hoppalong on the Initiative’s main viewscreen — blue, clear, inviting… and dull. The orange tabby was much more excited by the sight he saw through his techno-focal goggles when he teleported down to the world and found himself inside a giant spaceship hangar. One ship after another crouched on the expansive hangar floor, like row after row of giant, mechanical, sleeping grasshoppers.

LeGuin had never seen spaceships quite like these ones. They all seemed to be designed as short range cargo hoppers. Except there weren’t any other planets close enough to Hoppalong to be within their range. And even more bewilderingly, when LeGuin scanned the vessels with his uni-meter, the readings showed that their cargo holds were already loaded. Entirely loaded. And largely with perishable goods like fresh fruit and vegetables.

“Where’s this fleet planning to go, Sharro?” LeGuin asked the hooded rabbit who’d been following him as he walked from one ship to the next, scanning each one, and finding the same thing over and over. They were all ancient, possibly centuries old. Their metal was fatigued and rusting. The unstable isotopes in their engines had decayed far beyond usefulness. Every one of these ships needed a complete overhaul.

“That is not your concern!” Sharro snapped. His ears straightened up tall, causing his hood to fall back to his shoulders.

The rabbit quickly turned away, but not fast enough to stop LeGuin from noticing the mangy, blue patches on his cheek and neck, breaking up the fluffy brown of his fur. Sharro covered the scaly blue patches with one paw, and with the other, he pulled his hood back up, bending his long ears down.

“Okay…” LeGuin said. “But I am concerned about the state of these ships. They’re older than my great-grandcat!”

“But can you fix them?” Sharro asked.

LeGuin had been sent down to scout out the situation with the ships and determine what help he’d need from the rest of the Initiative’s engineering officers to fix them. But from what he’d seen, if the entire crew of the Initiative teleported down to the surface of Hoppalong and worked on these ships… the ships would still crumble to dust before they ever saw spaceflight again.

“Look,” LeGuin said, tail twitching nervously behind him as he tried to figure out a way to break the news to this rabbit gently. “Have you been maintaining these ships?”

“Maintaining them?” Sharro asked, scratching at his face under the shadow of the hood he wore. LeGuin guessed he was scratching at the patches of blue scales.

“Yes, spaceships need maintenance,” LeGuin said. Then, even though he’d meant to be polite and ignore the rabbit’s skin condition, he added, “Also, we have a doctor aboard our ship who could take a look at those scaly patches under your fur. They seem to be bothering you.”

Sharro’s ears shot up, tall and straight, knocking the hood back down. This time he stared angrily at the orange tabby, instead of turning away to hide his skin condition. The rabbit’s pink-rimmed eyes sparkled defiantly. “These scaly patches under my fur are exactly why you need to focus on fixing our ships, instead of lecturing me about the previous generations of my people who didn’t maintain them!”

“I’m sorry…” LeGuin said, though he wasn’t at all sure what he was supposed to be sorry for. This rabbit seemed to have completely unrealistic expectations for what could be accomplished. “I’m an engineer. Not a miracle worker.”

The rabbit’s nose twitched furiously. And then he pointed with a brown-furred paw at LeGuin’s orange-striped arm. “Maybe you need to become a miracle worker, because the pathogenic virus that inflicts my people with these degenerative scales seems to work far more quickly on your system than ours.”

LeGuin looked at his arm, and then he touched it, gingerly, with his other paw. Tufts of orange fur fell away, revealing scaly patches of blue. His skin was usually soft and pink under his fur, but these patches were a brilliant azure, contrasting starkly with his fur, and as hard and scratchy as a lizard’s scales. “What the hell!” he meowed. “You invited me down here, knowing that it would make me sick?!?”

“No,” the rabbit said, turning away again. “Honestly… I had hoped your people would be immune. But now, you must help us. If only to help yourself…”

LeGuin scratched at the hardened blue scales on his arm, as if he could rip away the illness inside of him with his claws. But the scales were tough and smooth; his claws slid over them without effect, and when he managed to snag needle-sharp claw tips between the scales, he only succeeded in hurting himself. Blood oozed between the scales, fresh and red against the sea-blue chitin. His body was changing, and he didn’t know how to stop it.

* * *

Back aboard the Initiative, Captain Jacques proudly led a delegation of five bunnies around the corridors of his ship. Two of the Hoppalongs were pure white — one snowy and the other more like milk — two were piebald, and the fifth’s fur was hazelnut brown. Each bunny wore a long hooded robe with the hoods down around their shoulders. The leader of the group was one of the piebald bunnies with a large brown spot over her left eye, named Colonel Hippity.

As the rabbit aliens hopped after the Sphynx cat, their long ears tilted, angling to listen to the thrumming hum of the ship’s powerful engine, and their fuzzy noses twitched, demurely showing interest in the many science labs the captain pointed out to them as they passed by.

Grawf followed along behind the bunnies, towering over them, and grumbling rudely when any of the visitors expressed too intense of an interest in any of the ship’s technology or showed a desire to step off of the path that the captain was laying out for them.

Captain Jacques disliked the idea of correcting one of his officers in front of diplomatic guests to the ship, but each time the bear growled, his own pink-furred tail swished unhappily. Eventually, he found himself forced to say, “Officer Grawf, that’s enough.” He stepped back through the crowd of bunnies, until he stood close enough to the giant bear to speak up to her in a quieter, almost hissed tone of voice: “These are our guests, and if they’d like to take a diversion through the astrophysics lab, then I’m more than happy to oblige.”

Grawf shifted her weight from one hind paw to the other and yanked at the chainmail sash across her chest. All the while grumbling.

“Do you have something to say to me, Officer?” Captain Jacques asked pointedly.

“As a security officer,” Grawf said, “it’s my responsibility to point out that our guests do not have any security clearances, and that you’re showing them potentially vulnerable parts of the ship!”

Captain Jacques blinked at the bear. “That astrophysics lab? You genuinely think that’s a particularly vulnerable part of our vessel?”

Grawf shifted weight between paws again. She was so large, it was like watching a mountain move. But she didn’t say anything. What could she say? The astrophysics lab was not a prime target, and the science studied there was esoteric — not immediately applicable to weapons construction or mapping out the colonies, star bases, and fleet movements of the Tri-Galactic Navy. Nothing vulnerable. In fact, it was an ideal laboratory to show off to the Hoppalongs. Captain Jacques wasn’t sure why he’d originally planned on passing it by.

“That’s what I thought,” Captain Jacques said eventually, punctuating the statement with a swish of his tail. “Watch yourself, Officer Grawf.”

The Sphynx cat stepped back to the forefront of the group of bunnies. By and large, they were a little shorter than him, unless he counted their ears, which rose higher than his own triangular ones when they stood tall. He led the bunnies into the astrophysics lab and directed the dog and cat scientists there to give the bunnies free reign to explore, and to explain anything to them that they wished.

While the bunnies poked around, Captain Jacques watched Grawf with concern. The Ursine officer had been, up until now, one of the steadiest, least easily perturbed officers that Captain Jacques had ever encountered. She was not only the size of a mountain, she generally had the calm placidity of one, even in the face of minor annoyances that would have made the captain extremely irritable.

He wondered if there was something about the Hoppalongs that particularly threw off the Ursine’s composure. Perhaps a pheromone that cats and dogs didn’t react to? He was about to call the ship’s doctor, an Irish Setter named Waverly Keller, on his comm-pin to see if she could check the ship’s databases for any clues, when his comm-pin chimed with an incoming transmission. He tapped the golden insignia pinned to his uniform and said, “This is the captain.”

LeGuin’s voice emanated from the pin: “Captain, this is Lieutenant LeGuin on the planet, and… We’ve been deceived.”

The captain turned away from the group of Hoppalongs, stepping back into a far corner of the lab. He lowered his voice and said, “Please explain.”

“The Hoppalongs suffer from a planet-wide viral infection that modifies their bodies, transforming them from warm-blooded mammals into cold-blooded reptiles.” LeGuin’s voice sounded shaky, but that could have been the quality of the reception on the comm-pin for a signal coming all the way from the surface of the planet.

“It sounds like you should get back aboard the Initiative as quickly as possible–” the captain began, but he was cut off.

“I’ve been infected, Captain.”

The captain looked at the group of bunnies in the astrophysics lab, examining the various display screens and standing far too close to his own officers. With a sinking feeling, Captain Jacques said, “Computer, please seal off the astrophysics lab and begin quarantine procedures.”

The doors to the lab slid shut, and alarms blared, flashing yellow lights. The bunnies hopped about excitedly, and Grawf began outright snarling. The previously peaceful laboratory had become a tiny tempest of chaos.

Captain Jacques told LeGuin to stay where he was and continue learning what he could about the Hoppalong’s fleet of broken down spaceships. Then he contacted Doctor Keller and asked her to scan the ship for traces of an infectious virus — or anything else unfamiliar that the Hoppalongs had brought aboard with them.

Perhaps that was why Grawf had become irritable. Perhaps they were both infected with the Hoppalong virus, and it affected her differently. As far as Captain Jacques could tell, he was no more irritable than usual for his feline self. Although, he was now feeling — rationally, he thought — quite annoyed with the Hoppalong visitors.

“I’m informed,” he hissed sharply at the leader of the bunnies, “that your people are infected with a highly communicable virus, and you may have brought it aboard my ship without warning us. Is this true?”

Colonel Hippety hopped toward the captain. “It is true, but–”

Before the bunny could continue, alarms rang out through the astrophysics lab. Different alarms than those caused by the quarantine. These were softer, chirpier chimes, accompanied by blinking lights of blue and green on various computer consoles.

“What’s happening?” the captain asked, turning from the leader of the bunnies to his own officers.

A calico cat with fascinated delight in her golden eyes said, “The gravity is shifting…” Her orange and white splotched paws moved over the computer console. “This is highly unusual. These readings are unlike anything I’ve seen before.”

“Is it safe?” the captain asked.

“I don’t…” The calico’s ears flattened as she considered the practical question rather than the sheer joy of research. “It depends. We seem to be safe for now. The fluctuations are concentrated on the far side of the planet, more than a thousand kilometers from us.”

“It is our moon,” Colonel Hippity said, raising her hood over head and casting her piebald face into shadow. The other bunnies followed suit, raising their hoods, covering their ears and casting their faces with their twitchy noses into shadows too. “It is coming back.”

The snowy white bunny said, “We are running out of time. If you are going to help us — and yourselves — it must be soon.”

“I don’t appreciate threats,” the captain said.

As he spoke, he heard a growl, deep and rumbling, come from Grawf’s direction. The bear’s jaw was clenched tight, and her lips had drawn back enough that her sharp teeth showed. This was not helpful. Captain Jacques already had a sick officer on the planet below, a roomful of deceptive bunnies, and gravity itself turning topsy-turvy on him. He didn’t need Exchange Officer Grawf trying to help out by physically threatening the much smaller Hoppalongs. The bear most likely meant well, but her behavior was more likely to escalate the situation into a regrettable incident than actually help in any way.

Captain Jacques wished he could order Grawf to leave the room… but they were still under quarantine, on top of it all.

The Sphynx cat raised his furless pink paws, carefully keeping his claws sheathed. “Everyone take a moment, please. Let’s handle each of these issues in their order of urgency–” He turned back to Colonel Hippity. “What do you mean, your moon is coming back?”

“Our moon’s cycle is lopsided — approximately one hundred years away, followed by only a few short days here.” Colonel Hippity’s nose twitched furiously as she spoke.

“Your moon’s cycle?” the calico cat at the computer panel asked.

“Yes, of course,” the milky white bunny said. “It’s an inconvenient truth of the dance between our worlds — Hoppalong must get by for a hundred years without the silver face of Sloumo to light our night sky.”

The bunnies all turned to each other, exchanging excited glances. The hazelnut brown bunny said, “None of us have seen it — only read the poems and heard the nursery rhymes.”

“The epic songs…” the milky white bunny added.

“Oh, yes!” agreed the other piebald bunny who had speckles of black and gray on her white cheeks. “I love the song, ‘Sloumo’s Rise’!” She began singing, “Love under a silver sky, amid the trees, painted by Sloumo’s reflected light. Will my tortoise come to me? Will he remember why? I wait for him, waited a hundred years under a star-filled empty sky…”

By the final line, probably the chorus of the song, all five of the bunnies were singing in harmony. A strangely lovely sound, following the blare of the quarantine alarm.

“Your moon… goes away for a hundred years?” the captain asked in dawning bewilderment.

“I know it’s probably a surprisingly long time…” the speckled piebald bunny said, seemingly done singing for now.

“No, no,” the captain said. “That’s not what surprises me–”

The calico officer blurted out: “It’s surprising that it goes away at all!”

Grawf’s low, rumbling growl which had become a part of the background noise in the lab evolved into a question: “Where does it go?”

* * *

Outside the spaceship hangar, Lieutenant LeGuin stared at the Hoppalong night sky. The blackness was punctuated by the usual scattering of stars, visible in night skies all over the galaxy. But the darkness deepened in a disc the size of a large dog’s paw, hanging just above the tree line. The stars within that disk flickered, dimming like candles being blown out by the wind.

LeGuin’s orange fur prickled, bothered by the stillness of the night air, and he scratched, ineffectually at the blue scales growing under his fur again.

The Hoppalong standing beside him muttered under his breath, and when LeGuin asked Sharro to repeat himself, he said, “I’ve been waiting for this moment all of my life.”

LeGuin and the rabbit looked at each other, but the Hoppalong’s gaze didn’t stay on him long. The bunny was focused on the sky.

“I did not expect to see the moon…” Sharro glanced at LeGuin again, cleared his throat, and then spoke more clearly as he returned to staring steadily at the sky. “When I was a young one, I imagined that by this day I might… be in love, and I would… kiss my lover under the light of the elusive moon.”

He went quiet, and both of them watched the darkening spot in the sky. Rabbit and cat stared at the blackness in space that became so black, it felt like it was bleeding light out of the sky around it. Then suddenly, black flipped to silver white, and the moon’s surface was blinding bright. For a moment. Then the pale face of the moon became a stolid, steady light — brighter than the rest of the night sky, but dim as any regular moon — that could have been shining there all along. Should have been.

Moons don’t disappear and reappear.

“Where does it go?” LeGuin asked, unknowingly mirroring Grawf’s question in the astrophysics lab of the Initiative.

At the same time, the Hoppalong beside him muttered, “I always imagined it would be the most romantic moment of my entire life.”

LeGuin turned away from looking at the unremarkable moon to watch the rabbit beside him. The rabbit who had lured him down to a planet where he’d become infected with a possibly incurable illness. The rabbit… who looked small and sad and filled with wonder at the simple sight of a moon.

Sharro’s nose twitched endearingly, and in between the mangy blue patches of scales, his fur was a beautiful, glossy shade of chestnut brown. His long ears tipped forward, bent over by the hood still over his head.

LeGuin was filled with an impulse and asked, “It’s not the same, but… Would… would you like to kiss a traveler from a planet far away?”

Sharro turned away from the moon now too and looked at LeGuin, measuring the sight of him. His furry nose twitched more slowly as he pondered the impulsive question, which surprised LeGuin, because the orange cat could feel his own heart racing. He felt vulnerable, but his techno-focal goggles showed him that, under the glossy brown fur, Sharro’s face was glowing with heat. He was blushing; he felt vulnerable too.

“Yes,” the rabbit said. He held out a paw toward LeGuin, and the cat took it. Warm paw in warm paw, they stepped closer to each other. The cat’s whiskers brushed against the softer whiskers of the bunny before their muzzles pressed together. The cat’s techno-focal goggles fogged up.

LeGuin imagined that rabbits must be kissing each other all over this hemisphere of Hoppalong tonight. The romance would follow the moon’s rise, tracing a path around the world for the next day.

The kiss was brief, but it left LeGuin tingling from pointed ears to twitching tail tip. The bunny visibly swooned as LeGuin stepped away from him, and the cat had to put out a paw to catch the bunny’s back, supporting him as he got his big feet beneath him again.

“That was magical,” Sharro said, staring down at his feet, seemingly afraid to look the stranger from the stars in his eyes again, now that they’d shared a moment of intense romance.

LeGuin smiled at the rabbit’s shyness. Usually, LeGuin was a shy cat. He didn’t let romance or sudden impulses overcome him. He felt more comfortable with computers and machines than with other cats and dogs. But he felt comfortable with Sharro.

“Tell me,” LeGuin said, “is the moon where the fleet of spaceships is supposed to fly?”

“Yes,” Sharro said. “The tortoises who live on the moon grind the edges off of their own shells to make a medicine that inoculates my people against… the transformation. When their moon appears, once every hundred years, we trade farm goods — mostly fruits and vegetables — for the medicine. If we can’t trade… I don’t know what will happen to us.”

“Or me,” LeGuin grumbled.

The rabbit looked up at him, eyes shining with the reflected light of the moon. “I am so sorry,” he said.

“It’s okay,” LeGuin reassured the bunny. Although, it wasn’t okay. But the choice to lure him down here, to risk his health, had not been Sharro’s alone. “I understand. The stakes are high.”

Sharro nodded solemnly. But there was a softness in his eyes. “You know, even if we cannot bring enough of the medicine to our world to save my people… Surely, your ship could take you to the tortoises directly. One dose… that couldn’t cost much.”

Now LeGuin nodded, slowly. The orange cat was deep in thought, inspired by Sharro’s stray comment. He needed to figure out if it would be possible to quantum teleport the goods on Hoppalong up to Sloumo, and in turn, teleport the medicine back down to Hoppalong.

The Initiative’s teleporters weren’t designed for that kind of massive, bulk transportation, but if LeGuin could enhance their range… Gears turned in his mind, picturing the alterations he would need to make to the teleporters. Could it be done? In time? He wasn’t sure…

But an entire people, a whole planet’s population depended upon him…

He had to try.

* * *

Doctor Waverly Keller, an Irish Setter with long, red fur, studied the shipboard computer’s scans of the lifeforms, displayed on the wall-panel beside the sealed door to the astrophysics lab. The scans showed biometric readings on all of the creatures — cats, dogs, rabbits, and one bear — quarantined in the astrophysics lab. According to the scans, there was indeed a virus-like infection hosted inside the rabbit’s bodies, but it showed no sign of having become airborne or having entered the bodies of the Tri-Galactic Navy officers in the room.

In fact, Dr. Keller had already passed that information along to the captain, still quarantined with the others, several times, but the Sphynx cat could be infuriatingly cautious. The door to the astrophysics lab stayed stubbornly sealed, and all of her patients were on the other side of it.

Dr. Keller placed her red-furred paw on the communications panel beside the astrophysics lab door, and said, “I have all of the necessary information on the computer console right here, and I’ve relayed it to the computers inside the lab as well. Just look at it, Captain.”

The captain’s feline voice emanated from the comm-pin on her uniform, “Are you sure there hasn’t been a change?”

“While we’ve been arguing?” Dr. Keller asked, beginning to feel flustered. “Yes! I’m sure! I’m looking at the scans right now! And the safest thing we can do for the ship — and all of our officers — is to move the Hoppalongs to the medical bay where we have better tools for controlling this quarantine.”

“Lt. LeGuin says he’s already become infected,” the captain objected, still obstinately on the other side of the sealed door. “If the Hoppalongs leave this lab, what’s to stop them from infecting the rest of the crew?”

“Most likely,” Dr. Keller said with as much patience as she could garner, “the concentration of the virus is orders of magnitude higher on the planet. I guarantee you, the Hoppalongs won’t infect anyone by walking down the corridor from one lab to another.”

“Then why is Ensign Grawf behaving so strangely, eh?” the captain asked.

“I don’t know,” Dr. Keller answered through gritted teeth. “But it’s not due to a virus from the Hoppalongs, and whatever is causing her strange behavior, I’ll be much better equipped to discover and cure the problem when we’re all in the medical bay together — where we should be right now — than while I’m standing in the corridor, on the other side of a sealed door from my patients!”

A moment of silence passed, and then the quarantine lights around the astrophysics lab door powered down. A moment after that, the door slid open. The captain stood on the other side, ears flattened against his skull and tail lashing behind him. The doctor had rarely seen him look so angry. He pointed with a steady paw at the Hoppalongs, and then at the lab door. “Everyone, follow the doctor.”

Doctor Keller’s auburn brush of a tail swished in relief as she led the infected bunnies toward the medical bay. She felt much better whenever her patients were in the medical bay. There was so much more she could do for them, so many more emergency protocols available inside the med bay than anywhere else on the ship. It was the safest room to be in. The safest room on the ship, and right now, probably the safest room in the entire star system.

Dr. Keller got each Hoppalong and each potentially infected crew member settled onto their own medical cots, and then she took each in turn, starting with the dogs and cats from the astrophysics lab. She scanned them, double and triple checking each individual for any signs of infection, before releasing the officers back to their duties.

The astrophysicists happily got their tails out of the med bay as soon as they were allowed, but Captain Jacques stayed behind, hovering beside the doctor as she scanned Grawf.

“I’m telling you,” Dr. Keller said, “there’s no sign of any foreign bodies in Grawf’s system.”

The captain’s ears flattened again as he tried to see the screen of the uni-meter in the doctor’s paws. She held it lower for him; the Sphynx cat was much shorter than the Irish Setter. The tips of his ears barely came up to the height of her shoulders. “Then why is she behaving so… irritably?”

Doctor Keller was tempted to snap back, “I don’t know; why are you?” But instead, she said in her calmest voice, the one she saved for the captain, “The only unusual reading I’m getting is an elevated level of adenosine. So perhaps Grawf hasn’t been getting enough sleep?”

The Ursine officer shifted uncomfortably as the Irish Setter said the word “sleep.”

“Is that it?” Captain Jacques asked, turning to the Ursine officer. “Is the bed in your quarters too small? We could synthesize a larger one.”

“It is not too small,” Grawf rumbled.

“Too soft?” One of the captain’s ears risked rising a bit from its flattened position.

“No.” Grawf stubbornly said nothing more.

“I can order you to get more sleep,” the captain said, not at all helpfully.

“I cannot sleep.” Grawf folded her arms across her chest, pressing the chainmail sash she wore into the fabric of her uniform.

“If you’re suffering from insomnia,” Doctor Keller said, “I can give you something to help you fall asleep.”

“No…” Grawf sputtered. “That is not… what I meant. If I fall asleep…” The bear turned her face away from the captain and doctor. It almost looked like there were glints of tears in her eyes. “I will not wake up.”

The captain and the doctor exchanged a glance, each wondering if the bear needed to be referred to a counselor rather than a medical doctor. However, Grawf continued, very reluctantly, speaking each word like it was a boulder being extracted from a mountain: “My people hibernate… for many months at a time… and if I go to sleep now… I will not wake up…”

“For many months,” the captain said, slightly faster than Grawf. “Yes, I get the idea.”

“Instead of a sedative to help you sleep,” Doctor Keller offered, “I could prescribe a stimulant to wake you back up?”

Grawf shook her head; a mountain grumbling objections. “I’ve been setting louder alarms, and taking stronger stimulants every day.” She held up a paw, and the mammoth appendage shook unsteadily in the air. “The stimulants are making me shaky. The alarms have almost stopped working.” She tucked the shaking paw self-consciously under her other arm and admitted in a low voice, “I was half an hour late for my shift today…” She locked eyes with the captain and said what he was thinking: “…and I’ve spent the entire shift irritable. I am unable to perform my duties. I need to hibernate.”

Grawf lumbered off of the tiny med bay cot and stood at attention. Bravely keeping her voice steady, she said, “I understand that this means I will need to be returned to my own people. We are not fit for your… fast-paced, unrelenting society.” She bowed her head forward. “I thank you for the time that you’ve given me here.”

“Now wait a minute!” the captain exclaimed. “You’re making a lot of assumptions. How long do you need to hibernate for?”

Grawf shuffled uncomfortably from one massive hind paw to the other. “Six months,” she eventually admitted. Although, the truth was that most of her people had already been hibernating for six months by now. But the bear figured that if she slept for the second half of her usual hibernation cycle — one year, every seventh year — that would be enough to refresh her. With only six months sleep, she should be able to rejoin the unrelenting world of these energetic little cats and dogs.

Yet Grawf held no delusions that a vessel full of dogs and cats who never needed to hibernate would be willing to tolerate her — in comparison — lazy indolence.

“Done,” the captain said.

“What?” Grawf rumbled in utter surprise.

“Is there anything you need?” the captain continued, ignoring the bear’s total bewildered bafflement. “Anything we can do to make your hibernation go better?”

“No…” Grawf said.

“Then, six months personal leave it is,” the captain said. “Would you like to return to your quarters right away?”

“Well… yes, actually,” Grawf admitted, still trying to absorb the idea that instead of being fired and returned to her home world in shame, these dogs and cats were willing to work with her needs. She felt a huge swelling of gratitude deep inside, and before she could restrain herself, Grawf had wrapped both the captain and the doctor in a giant bear hug.

One arm crushed the small Sphynx cat against the bear’s chest, and the other arm pressed the larger — but still small, compared to a bear — Irish Setter against her side. “Thank you so much,” she rumbled. The tears that had glistened in her eyes earlier began to flow freely. She was simply so relieved that she could stop working so hard to stay awake. Finally, she could get some real, deep, long-lasting sleep. She would finally feel rested again.

Once Grawf had returned to her quarters, the doctor was able to focus on her Hoppalong patients. There was a general restlessness among the rabbits; they were all keenly aware that they were missing a once-in-a-century event on their world, and they seemed increasingly doubtful that they were missing it for a good reason.

Doctor Keller scanned each rabbit thoroughly and visually examined the patches of scales — blue and in some cases green or yellow — growing under their fur. She felt the rough scales with her paw pads, sniffed them with her nose, and stared hard at them. Then she pulled out her uni-meter and scanned them again.

“Look,” Colonel Hippity said, “the best and brightest doctors on our world have been studying our affliction for generations. No offense to your–” The rabbit waved her paws dismissively towards the rest of the med bay. “–clearly high tech toys, but we already know the only solution to our problem. And it involves the engineer that you teleported down to our planet fixing our space fleet.”

Doctor Keller closed and holstered the uni-meter she’d been using to scan Colonel Hippity. “How do you mean?”

“The tortoises of Sloumo have our medicine waiting for us — we need only transfer our trade goods to them, and then the ships can return with enough medicine for the next hundred years.”

“That’s not a cure,” Doctor Keller said. “If you’re permanently reliant on the medicine, then you’re only treating the symptoms. Besides, the more that I study the scans of the virus in your bodies, the less convinced I am that it’s a disease at all…”

Colonel Hippity’s face contorted with anger, a visage of cuteness twisted into a mask of hate. “How dare you belittle the pain of the curse my people suffer–”

The rabbit’s tirade was cut off by the chiming sound of a call to the captain from the bridge. Captain Jacques accepted the incoming message on one of the med bay’s computer screens. The face of a collie dog appeared on the screen — the ship’s first officer, Commander Bill Wilker.

“Captain,” the collie said, “we’re receiving a request from the people of the moon that recently appeared. They’d like to meet with you.”

“Aboard the Initiative?” Captain Jacques asked.

“Yes, Captain.”

“Tell them we will teleport their delegation aboard presently,” the captain said. “Teleport them directly to the delegation room, and I’ll meet them there.”

All of the bunnies in the med bay began whispering to each other excitedly, culminating in Colonel Hippity saying, “Captain Jacques, we would be most grateful if we could join you in meeting with the visitors from Sloumo.”

“None of us have ever met a tortoise!” exclaimed the hazelnut brown bunny.

The captain turned to the doctor, and the Irish Setter shrugged. “Captain,” she said, “as far as I can tell, the condition the Hoppalongs suffer from cannot possibly be contagious to us.”

Captain Jacques lowered his voice and said to the doctor, “Lieutenant LeGuin insists that he’s been infected.”

The doctor shrugged again. “Regardless, based on my readings, he couldn’t possibly be suffering from the same affliction.” She stepped close to the captain, lowering her red-furred muzzle toward his pink-skinned ear and whispered, “Whatever’s happening to the Hoppalongs is a natural occurrence, not caused by foreign bodies in their systems. The organelles that looked like viral agents at first… are actually being generated by their own genes.”

The captain blinked. “Can you fix it?”

“Not yet,” Doctor Keller said.

“Keep working on it,” Captain Jacques said. “Meanwhile, I have some tortoises to meet.”

Doctor Keller drew blood samples from each of the rabbits before releasing them from the med bay. The Irish Setter was already deep in her studies as the diplomatic team filed out.

* * *

As soon as Lt. LeGuin received word that he was cleared to return to the Initiative — since apparently, Doctor Keller didn’t believe that the blue scales covering most of his arms and shoulders were contagious — he brought Sharro with him and teleported back aboard.

Of course, if they weren’t contagious, how had he gotten them? But LeGuin didn’t have time to worry about that. He had a teleporter to reprogram. Preferably, before he shapeshifted entirely into some sort of blue lizard.

Dr. Keller paged LeGuin through his comm-pin, and ordered him to report directly to the medical bay. But LeGuin didn’t have time for that either. The orange fur was sloughing off his cheeks and ears now, revealing smooth, azure scales underneath. He trusted the doctor, but Sharro said the tortoises already had a cure.

Why bet on the doctor’s ingenuity when he could have the sure-thing of a prefabricated cure, already waiting on Sloumo? All LeGuin had to do was reprogram the specs of the teleporter to widen its beam. And maybe beef up the buffering algorithms so that the quantum pattern of the teleported materials wouldn’t drift dangerously during reassembly…

LeGuin took comfort from explaining his work to Sharro as he labored; he took less comfort in watching the beautiful chocolate-furred bunny rabbit morph before his enhanced vision. Sharro’s tall ears wrinkled and withered like autumn leaves, until they looked like they’d disintegrate at the lightest touch. His glossy fur fell away, until his whole face was blue and gaunt; his nose no longer twitched. There was no glossy chestnut fur to twitch, just two slits of nostrils in a hauntingly blue face.

LeGuin feared he’d look the same way soon, and he doubled his efforts towards reprogramming the teleporter. As soon as his work was done, LeGuin took Sharro by the paw. Except, both of their paws were more like talons now — furless, scaly, blue. He knew he was breaking protocol, being so familiar with a diplomatic guest aboard their vessel, but he was scared. Sharro was undergoing the same transformation as himself, and ever since their kiss, he felt close to the Hoppalong.

If they couldn’t get the medicine from Sloumo, LeGuin might find himself dying from this strange plague, and he’d rather die among others sharing his plight than alone, surrounded by the pitying gazes of perfectly healthy cats and dogs.

“Come on,” LeGuin said. Even his voice was changing, growing deeper and more raspy. “We need to get to the captain. Tell him our plan.”

“And get the medicine…” Sharro whisper-rasped.

LeGuin nodded, and more orange fur fell to the deck, leaving a ring of shedding around his hind paws. He feared to see what he looked like now. His techno-focal goggles itched against the side of his head; usually they rested on a layer of fur, but now they pressed against scaly skin. If he were cured by the Sloumo medicine, would his fur grow back? Would he ever be the same orange cat again?

Paw in paw, LeGuin led Sharro down the corridors of the Initiative, towards the bridge, where he expected to find the captain. Along the way, Dr. Keller caught up with them and followed, barking orders and commands that he must come to the medical bay at once.

LeGuin ignored the dog and increased his speed, breaking into a full run. When he burst onto the bridge, only to find the collie dog first officer currently in command, he pulled Sharro after him and barged straight into the delegation room, connected to the back of the bridge. His guess was right: the captain, the delegation from Hoppalong, and also three tortoises were inside the long, curved room.

“Can you explain this interruption?” the captain asked, his voice piqued but his pink ears resolutely tall.

Before LeGuin could answer, Sharro’s hand tugged at his, and the orange cat looked back to see the Hoppalong — now more lizard-like than rabbit-like — stopped in his tracks and doubled over, seemingly in pain.

Sharro pulled his paw away from LeGuin and clutched his arms against his sides. “My back!” he rasped. The Hoppalong dropped to his knees, and then lowered himself to the floor. He curled up tightly, his arms wrapped around his legs.

“Are you okay?” LeGuin asked. He knelt down by the writhing Hoppalong’s side and placed a tender, comforting paw on Sharro’s back. Through the linen-like fabric of Sharro’s cloak, LeGuin felt a stiff, ungiving surface. Not at all like flesh and fur… or even scales and fur. More like…

LeGuin looked up at the three tortoises. Their flipper-like hands were covered in blue-green scales; their faces were wrinkly and gaunt like Sharro’s had become. And their curved backs were covered by stiff, ungiving shells.

LeGuin’s mouth dropped open. He looked at the other Hoppalongs and saw that their robes were clearly trying to obscure the scaly patches breaking out on their own arms and faces. Patches of blue, green, and even yellow. When LeGuin didn’t think of the patches as mangy, sickly fur, but rather as perfectly healthy scales shining through, they had almost a gemstone brilliance to their colors. Sapphire, emerald, peridot, citrine.

“You’re not different species,” LeGuin said.

“Of course we’re not,” one of the tortoises said.

Doctor Keller appeared in the door of the delegation room and gasped at the sight of Sharro curled on the floor in pain. She knelt beside him and snapped open her uni-meter. The device bleeped and blooped as the red dog scanned the writhing rabbit… or lizard… or maybe, tortoise?

“I can give you something for the pain,” Dr. Keller said. The Hoppalong nodded, and the dog injected his shoulder with a medi-patch she’d had in her pocket. “But according to my scans, the process you’re undergoing is completely natural. Like puberty. Well, some kind of second puberty.”

“Or a caterpillar transforming into a butterfly,” LeGuin muttered, staring at his new friend. He looked at the doctor and said, “What’s wrong with me? Because I know I’m not a pre-pubescent tortoise.” He held an arm out, and she obligingly scanned it.

“Your body is flooded with pheromones,” Dr. Keller said. “And it’s causing physical changes in your body, much like it would if I gave you a condensed shot of hormones. But the changes should be temporary once the pheromones are flushed from your body. I think you simply overdosed on them by being on the surface of a planet where–” The dog looked around the room at the anxious, transforming rabbits and the preternaturally calm tortoises. “–well, from what I’ve learned, most of the population is undergoing a process not dissimilar to adolescence.”

Sharro’s body had relaxed, but he was still curled up on the floor. He reached up to touch one of his ears, and the withered thing simply fell away from his head, crumbling to dust as it fell.

LeGuin winced and reached up to touch his own ear. The fur fell away at the touch of his paw, but the ear itself felt shaped the same, simply smooth with scales instead of soft with fur. “I’ll really change back?” LeGuin asked. “Naturally? With no need for medicine?” He felt an immense relief, even asking those questions. He’d been afraid he was dying at worst or transforming permanently into a blue lizard, at best. He didn’t want to be a blue lizard. He was happy being an orange cat.

“That’s right. In fact, none of you need medicine.” Dr. Keller looked around the delegation room, catching each of the Hoppalongs and the tortoises with her eye. “Except maybe pain medication to manage the severity of your symptoms.”

“That can’t be right!” Colonel Hippity exclaimed, stamping a long foot. “Look at him!” The rabbit pointed with a scaly paw at Sharro who was still curled up on the floor.

Feeling all of the eyes in the room turn toward him, Sharro sat up and drew his cloak aside. He gestured for LeGuin to help him, and the orange cat — who looked less like an orange cat than he usually did — helped Sharro remove the cloak entirely, and then helped pull the loose shirt off over his head, revealing a hardened patch of skin in the middle of the Hoppalong’s hairless, scaly back. Sharro touched his back and turned his now-earless head as far as he could, but he couldn’t see the hardened patch. “What does it look like?”

“There are hexagonal patterns…” LeGuin said. “Green hexagons, bordered by lines of brilliant blue. It’s… actually quite beautiful.”

“My… shell,” Sharro said. He sounded confused, but also strangely proud. “Will it keep growing? Until it covers my whole back?” He looked to the tortoises for confirmation. All three of them nodded.

“Did you really not know?” asked one of the tortoises with yellow lines delineating the hexagonal pattern on her shell. “Have you all forgotten so much during the last one hundred years?” She looked at each of the Hoppalongs in turn, and in turn, each of them looked away, abashed and embarrassed.

“I guess this is what happens when you let children choose to stay children,” sniffed another tortoise, dismissively shaking his head. This one’s shell had octagonal patterns instead of hexagons in a variety of shades of blue and green.

“But… the medicine…” Colonel Hippity tried to say more, but the weight of the situation seemed to hold her down.

“It’s an aging suppressant,” the third tortoise said.

“Then… we won’t die without it?” Colonel Hippity’s own ears looked nearly ready to fall off.

“You’ll die if you keep taking it,” the tortoise with yellow lines around her hexagons said. “Without it, you can live as long as we do.”

Sharro nearly leapt to his feet. He seemed to be feeling much better. “Why! You don’t just look like the tortoise from the painting The Last Visit From Sloumo — you ARE that tortoise!”

The tortoise’s gaunt, wrinkly face twisted into a smile. “Indeed. Toretelli was a wonderfully talented painter. I enjoyed posing for her, and I’m glad her work is still remembered. I wished she would have come to Sloumo and spent the last hundred years in quiet repose, painting and developing her talent. But alas.”

“But alas,” the other two tortoises agreed.

“Her work changed the history of art on Hoppalong,” Colonel Hippity said, strident and quivering with rage. “And you would have had her leave instead?”

“How long ago did she die?” the tortoise asked.

Colonel Hippity looked away, but Sharro answered: “More than eighty years.”

All three tortoises nodded, their bald heads bobbing sadly. “She could have been a part of our delegation; she could have been standing here today, if she had been willing to come with us.”

A complicated silence descended over the room. Even the captain, usually forthright and commanding to the very tips of his pink ears, seemed reluctant to break the silence.

Finally LeGuin asked, “But why? If Hoppalongs can live so much longer once they… transform, then why would they take the medicine that keeps them… young?”

“You have to ask?” The tortoise tilted her head at the half-transformed orange cat. “It’s fun being young. Childhood is full of boundless energy and delights, and being an adult is full of hardships and shades of gray. That’s why we grow our shells to protect ourselves from the weight of time and uncertainty. But childhood cannot last forever, and trying to extend it…” She shrugged her scaly shoulders, a stiff gesture under the curve of her shell. “Sometimes, it’s the right choice. For a while. But it comes with a toll.”

In the awkward standoff that followed between the tortoises and the transforming rabbits, LeGuin explained that he’d altered the ship’s teleporters to where they could safely teleport the entire cargo load of the derelict Hoppalong space fleet to Sloumo and return the stockpile of anti-aging medicine in its place.

The Hoppalong delegation were no longer sure whether they should take the shipment of dubious medicine from Sloumo. Perhaps, it was time for their entire world to grow up. However, Captain Jacques convinced them that they could always warehouse the medicine, and make up their minds about how to handle it later, perhaps on a case by case basis. After the Initiative was on its way.

* * *

As the starship Initiative flew away from the blue-green world and its silver moon, soon to slip back into a hyper-spatial dimension, an orange cat re-growing his fur pondered his impulsive brush with romance. The kiss he’d shared with a rabbit under an elusive moon had almost certainly been spurred on by the pheromones flooding his system; the wild, irrepressible urges of youth. And as he felt the kitten-soft fur growing back on his arms, he could understand how the Hoppalongs had traded longevity for youth, even if it wasn’t a choice he would make.

Doctor Keller marveled that an entire world could mistake growing pains for illness for nearly a hundred years, and Captain Jacques felt grateful that cats and dogs had had humans to guide their way from a sub-sentient kittenhood into an uplifted adulthood, rather than struggling through their growing pains alone.

But Grawf simply slept, hibernating her way through the stars.

Read more stories from Tri-Galactic Trek:

[Next]