by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Daily Science Fiction, July 2012

It feels strange to me, deep in my stomach, that I can’t find my ten-year-old girl in real life — but that, maybe, I can find her here.

My hand shakes on the computer mouse as I log in to Second World, using one of the default avatars — a woman with straight blonde hair like a plastic shell and the expressionless face of a crash-test-dummy. I try messaging my daughter through the in-game chat window right away, but my message bounces back. I check for her name, “fluttercat,” on the online user list, but it’s not where it should be between “flutter14” and “flutterkid.” My throat constricts with a swallowed sob, but I refuse to believe this tenuous connection to my missing daughter won’t pan out. Maybe she’s set her status to hidden.

I begin navigating my avatar through the in-game trams from one city to the next, bumping into walls and getting stuck in the occasional corner. Everywhere, I look for Daria’s avatar. Yet, I have no real plans until I notice the scribbles of flowers taped to the corner of Daria’s monitor and remember her latest Second World obsession. If she’s here, I know where she is.

I wish I could teleport there, but I haven’t unlocked that ability on this avatar. I don’t have a personalized avatar, because I don’t really play Second World. I know my way around, though, because I’ve watched over Daria’s shoulder more than enough.

I take the trams to the right city and head out of town, through the virtual forest. The trees have leaves like fractals, and the sunlight streams down in shafts filled with swirling dust motes. If you watch long enough, you can see the swirling patterns repeat. I’ve watched my daughter come this way so many times, but I’ve never followed the path myself. I’m afraid I’ll get lost among this forest of clones — each tree clearly sharing the same basic code.

Then I see the glade Daria loves open up before me. And there she is.

Daria is curled up with her arms around her knees in the middle of a sunny clearing, filled with fantastical flowers drawn by some of the greatest visual artists in Second World.

Daria’s wearing the most complicated avatar I’ve seen her in. I know it’s just an avatar, but she designed it. And I can see all her pain reflected in the changes that her virtual self has undergone in the past year.

To begin with, she was simply a cat. An anthropomorphic feline with pointy ears, whiskers, and a twitchy tail on the body of a little girl. It was funny watching my daughter turn herself into a cat on the computer after all the years she’d spent pretending to be one.

Then her dad and I started fighting. After each big fight, I noticed a new feature. When she saw him throw the thermos at me, she added butterfly wings. When he tore the door to the living room off its hinges, she added a mermaid tail.

When Ken and I told her we were getting divorced… That’s when she added the tortoise shell. A big green shield covering her avatar’s little back. The way her butterfly wings fold up under it always makes me think of a ladybug. Her avatar is painfully cute. And painful.

Today, she’s added a pearlescent unicorn horn between her kitty ears. And matching spikes all over her shell.

“Your dad’s gone,” I type.

Her avatar’s mouth starts moving, but a text bubble doesn’t pop up on the screen. Belatedly, I remember that the goggles I bought her are wired with a mike. So, I turn up the sound and hear my little girl’s voice come out of the computer speakers. Quietly but with a venomous edge, she says: “I won’t go with him. I’ll never go with him.”

I told Ken that she didn’t want to see him. But, I guess, if Ken had ever listened to me and believed the things I said, we wouldn’t be here today.

“We called the judge,” I type, omitting the part of the afternoon where Ken and I stood on the front step yelling at each other, while Daria’s bags sat ready by the door — but no little girl in sight.

When Ken got it through his head that I wasn’t hiding Daria — I didn’t know where our daughter was and I was just as scared by that as him — he stopped calling me names that I cringe to think Daria might have heard. (What if she was hiding in the bushes? Listening?) Then, we started looking for her. We called all of her friends, and even her teacher. No one had heard from her.

After a few hours driving around, checking the local parks, Ken took it upon himself to call the judge. He thought he’d get Daria for an extra weekend or two, as some sort of punishment to me for not having her ready and waiting for him this time. His plan backfired.

“The judge talked to the court counselor,” I type, trying hard to keep my hands steady. “The one who talked to you about who you wanted to live with?”

Daria’s butterfly wings rustle at the edge of her shell. I can’t tell if she’s nodding. Her avatar’s expression is hard to read, but I continue anyway. “They’re not going to make you visit your dad on weekends. If you really don’t want to, they won’t force you.”

A small part of me feels triumphant that Daria’s behavior has won this fight for me. The idea of leaving her alone with Ken almost kept me from divorcing him. But I told myself he wouldn’t hurt her. And she was exposed to his yelling anyway. I couldn’t protect her from that.

I’m still trembling in fear, both from fighting with Ken and worrying about Daria. She’s not talking to me, and she could fly away with those butterfly wings or simply log out at any moment. Meanwhile, I keep picturing my baby girl squatting in some gritty, cold, alleyway downtown. Goggles on; attention to the real world off.

“Daria?” I type. “Please still be there.”

Daria’s winged-merkitty avatar starts rocking, and her voice pipes through my computer speakers, high pitched and small: “I d-don’t have to s-see him?” The spikes on her shell seem shorter, less pointed at the tips.

“NO,” I type, losing my internet cool and using all-caps. My blonde human avatar leans forward and puts her hands out in an animation automatically triggered by the word. “I mean,” I type, trying to soften it, “only if you want to.”

“I don’t,” she whispers.

“Okay,” I type. “Where are you? Please tell me so I can come get you.”

“Just you?” she asks.

“Just me.”

“Well…” Daria says, in the tone that I know means she’s embarrassed. The spikes shrink even more; they’re pearly nubs, a mere decoration in the shell’s pattern now. “I’m at the library,” she says. “They have a really nice set up with free wi-fi and super plush chairs. They don’t seem to mind if you hang out here all day.”

I feel like collapsing with relief. I type, “STAY THERE.” Then, I run for the door, not even bothering to log out of Second World. I can’t wait to lay eyes on my daughter. Yet, as I drive to the library, I realize that, in a sense, I’m already with her. My generic, default avatar is sitting in that field of flowers next to my daughter’s complicated one.

Maybe, once we get home, Daria can help me start customizing it.

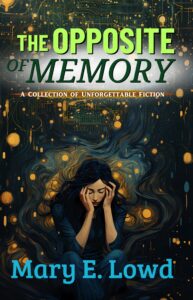

Read more stories from The Opposite of Memory:

[Previous] [Next]

That’s really nice. I never got the hang of 2nd Life myself….