by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Commander Annie and Other Adventures, November 2023

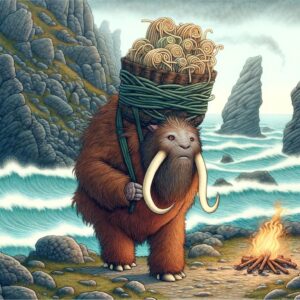

The Noodlebeasts came from the North. They traveled the Rocky Shores with their baskets of noodle-seeds, eating only as many as they needed to survive. The rest they saved for their arrival. It was a long journey along the crooks and crags and crannies. At night, they found safe nooks, protected from the beating of the ocean waves. There, they built cozy fires, toasted noodle-seeds for their supper, and sang songs about the world they were traveling toward.

Nawry was born near the beginning of the Noodlebeasts’ grand journey and spent most of the trip as a babe, riding in a basket strapped on his mother’s strong, broad back. His brown Noodlebeast eyes peeked over the swaddling wrapped around him and watched the colors of the old world, the world he was born into, fade away and be replaced, slowly, incrementally, by the Noodlebeasts’ new home.

“Now,” said the Grand Elder on a day like any other. His voice was barely a whisper under the roar of the pounding waves, but Nawry heard him. Since the day Nawry began walking, he always walked close to the Grand Elder.

“Now,” the Grand Elder repeated, louder. “Now, we are here.”

Until the Grand Elder spoke, the rocks around them were indistinguishable from all the boulders and stony protrusions the Noodlebeast parade had passed in their long travels. After the Grand Elder’s momentous words, the rocks around Nawry were immediately different in his eyes. They were rocks worth knowing, exploring. They were rocks he would see again, instead of a meaningless pastiche of grays that would pass before his eyes and then away again. Never to be repeated. Yet, also, to be repeated endlessly. Here was the end.

At that end lay a time and place of great growth. Stone huts grew out of the ground, under the coaxing flippers and powerful arms of the Noodlebeast horde, forming a small village. The same furry hands planted precious noodle-seeds, finally emptying the baskets that had been only sparingly sampled from for so long. Over it all, the baritone songs of building and sowing, rusty from disuse, replaced the Noodlebeasts’ traveling songs.

And Nawry grew up.

By the first harvest, Nawry declared himself a painter. His Aunt Jeminee painted, and he followed her about, learning to make dyes from the petals and leaves of the blooming noodle-flowers, learning to make pasta paper from the starchy flesh of noodle-fruit. He cast his canvas beside Jeminee’s and held his brush before him, striking her same pose. She smiled at her nephew, but it wasn’t her praise he sought after.

The handful of Noodlebeast babes younger than Nawry, born near the end or entirely after the grand journey, sat at his feet, adoring him. “I like your latest painting best,” one would say. Another, not to be outdone, would say, “I like them all best.”

“You can’t like them all best,” Sealia, the first, answered, “It doesn’t make sense. Right Nawry?”

“Don’t bother him!” Ktory admonished. “He’s painting. Is this a painting of the old world, Nawry?”

“Well,” Nawry said, standing back and looking at his handiwork, “It’s supposed to be.”

Aunt Jeminee looked down at her nephew’s canvas and frowned. “Hmm,” she said. It looked like she might say more, but the moment passed. She went back to her own painting, and Nawry found himself being begged to tell the story of the Grand Journey to the younger Noodlebeasts once again. He stayed ensconced in their querulous adulation until the late bonfire that evening, but his aunt’s frown and unspoken words followed him about, almost as insistently as Ktory and Sealia. In the end, Ktory and Sealia were less persistent, and Nawry found himself seeking out his aunt after they’d gone to bed.

“What did you think of my painting today,” Nawry asked, seating himself beside Jeminee. She was sitting on the inland side of the main bonfire, picking through a bowl of tagliatelle and rock shrimp. Nawry helped himself to one of the limp, flat, fresh tagliatelle noodles in her bowl. The adults told him to savor the freshness of harvest season noodles, but Nawry couldn’t fathom exactly what they meant. He’d never eaten dried, remoistened pasta. He’d been too young to eat solid foods near the beginning of the Grand Journey, before the travelers had run out of the dried pasta they’d brought with them. He remembered meals of mashed, baked noodle-seeds, but, even after being dried, the noodles themselves had to be better than that.

Nawry looked up at his aunt, who was staring into the dancing flames of the fire. Its circle made their entire world; the rest of the world lost into the high contrast with dark, dark night.

“It was missing something,” Jeminee said.

Now it was Nawry’s turn to frown. “I know. I can’t get it right.” He threw a pebble into the fire; sparks flew up from where it fell.

“Don’t worry,” Jeminee said, patting the smooth fur on the top of his head, ending with a quick ruffle of the bristly fur around his Noodlebeast tusks. “Whenever I paint the old world, it comes out the same way.”

“Missing something.”

“Yes.”

Nephew and Aunt sat staring at the fire until Nawry yawned, and Jeminee shooed him off to bed. In his dreams that night, the elusive, missing something danced just out of Nawry’s reach, darting around the nightly fire, behind the wet, gray rocks. Nawry chased it and found himself running backward along the shore, back to where he’d been an infant, staring out at a world he couldn’t remember well enough to paint it.

Nawry kept trying to paint the old world, but his failures didn’t consume him the way they did Jeminee. He was a growing boy, and there was too much in the new world to interest him for a lack from the old to haunt him. Much.

Nawry swam in the roiling waters, holding his breath for longer and longer times as he tested out his Noodlebeast lungs. He paddled his way along the calmly drifting waters of the ocean floor, examining coral and anemones until the burning in his chest would bear no waiting. Then he’d spiral upward and explode above the surface in a cacophony of splashes and gasping.

When the sea lost its charm, Nawry forged inland, exploring the autumnal forests that crowded the edge of the rocky shore. The deciduous oaks and maples reigned resplendent in their evening wear, designed for the evening of the year. Nawry tried every native berry and root he could find for new dyes. Mashed roots yielded a musky yellow paint; sour berries bled a brilliant red.

Jeminee thanked her nephew every time he brought her a new hue of paint to work with, but her paintings continued to mock her. “I wonder sometimes if I can even remember the old world right.”

Nawry didn’t answer her; he knew he couldn’t remember.

In addition to looking for new sources of paint, when Nawry explored he kept a lookout for native delicacies with which to variegate the evening Noodlefeasts. So, after bringing the sour red berries to his aunt for their redness, he brought them to his mother for their sourness.

“I thought these berries,” Nawry said, showing his flippery hands, full of little red berries, to his mother “might go well with penne petals.”

Nawry’s mother tried one and nodded. “Yes, that’ll work.” She put her cupped hands, the webbing stretched wide to make a broad bowl, out toward Nawry, and he poured the berries from his flippers to hers. “Shame though,” she said. “They’d go better with farfalle flowers.”

“Why’s that a shame?” Nawry asked. “I can bring more berries when we cook the farfalle.”

“We won’t be cooking farfalle,” Nawry’s mother said. “None of the farfalle seeds have sprouted, and usually the shore would be covered with their butterfly-like flowers by now.”

Nawry could tell that his mother felt this as a great loss. Confused by her bereavement, Nawry went to his aunt and asked if she had any paintings of farfalle in bloom. She looked at him strangely, and Nawry shifted uncomfortably. He didn’t like the somber mood the mention of farfalle struck in his adults.

“I haven’t tried painting farfalle,” Jeminee said, putting a paint-encrusted hand to the collar of her tunic. Just as Nawry was going to thank her and leave, escape the oppressing air of somberitude, Jeminee drew out a cord from around her neck that had been hidden under the cloth of her collar. She held the pendant at the end out toward Nawry. “It’s dried,” she said. “Hardly the same.”

Nawry reached out and touched the hard, sandy colored piece of pasta. It crimped in the middle, and he could feel the bulge of a mature seed, ready to be planted. The two wings flared out to ragged edges creating, as his mother had said, the shape of a butterfly. He tried to imagine fields of farfalle carpeting the shore, blowing in the ocean breeze. Little pasta flowers flying on their stalks above the water-washed rocks…

“It’s pretty,” he said.

“Tasty too. The tastiest.” Jeminee lifted the cord over her head and held it toward Nawry. “Here,” she said, “You wear it now…”

She didn’t finish the sentence, but Nawry could hear the words echoing, unsaid, anyway. “…wearing it makes me sad.” Nawry shuddered but took the gift.

Nawry felt better once he was away from the shore, romping through fallen drifts of amber leaves. Every day more leaves fell and carpeted the ground in their orangey reds. Yet even more leaves clung to their waning home in the sky. Nawry loved the forest, and he tried to convince his younger friends to explore it with him. But their parents balked, and even though they could have come, Ktory, Sealia, and the others absorbed their parents uncertainty.

So, Nawry romped alone. He didn’t mind; the forest felt warm and cozy, alight with the colors of an evening bonfire. But as the days grew shorter and colder, and the leaves grew thinner on the trees, Nawry’s romps grew lonelier. He was close to abandoning them altogether. Then he discovered Aumna’s glade.

It was on a day when he took the left path away from the Noodlebeast village, went through the brambly thicket, and climbed the steep knoll. From the top, Nawry could see leafy trees in the distance. Almost all the trees were bare by then, so the patch of brilliance among all the barrenness stood out like a topaz set in silver. Nawry headed straight toward it.

A half hour’s hike through the clawing undergrowth brought Nawry to the far edge of the brambly thicket. He’d never traveled so far through it before. Now he wished he had. For on the far side, he found a perfectly tended copse, threaded through with winding footpaths. And all the trees were still warmly clothed in their autumn gowns. It was much more cheerful than the forest of wintry, stickly trees on the rocky shore’s side.

Nawry followed the footpaths from one to the next, always heading toward the center of the copse. He could tell he was getting closer because the paths kept growing wider, as if they were heading toward something important, and the leafy underbrush gave way to garden patches.

There was a patch of curled up butternut squash, looking cozy in their beds on the ground. There was a patch of tomato plants, supported by metal cages and plump with rosy fruits. Then, there was a patch of ruddy harvest pumpkins.

The path led through the pumpkin patch, to a little thatched cottage at the far edge. The cottage gleamed gold with fresh straw roofing, and the front door swung open invitingly, creaking slightly in the wind.

Nawry noticed it was warmer here, in the middle of the copse, than it had been back on the Noodlebeasts’ shore. Warm enough to leave a front door open… Who was inside? Nawry wondered. The Noodlebeasts hadn’t met anyone yet in this new land. They’d seen small animals, but no other people. Would Nawry’s adults want to meet other people? He wasn’t sure, and he wasn’t sure if the choice to introduce himself, and by extension his people, to the cottage’s occupants was his to make.

He nearly decided to return to the shore, when he found himself fingering the fossilized farfalle around his neck. He wasn’t ready to go back to that sadness. He lived in this world, and he didn’t feel like mourning an old one. A world he’d never lived in. Not really.

So, Nawry approached the door. Before he was close enough to knock, a rich alto voice sang out to him. “Come in,” she called. “Have some hot persimmon cider with me. I’ve just heated it.”

Nawry hesitated, but he knew the woman obscured inside the cottage meant him. And although he couldn’t have explained it and it made no sense, he was sure she hadn’t mistaken him for anyone else. “Thank you,” he said, remembering his manners, and stepped into the cottage.

The furnishings were simple and wooden — a table and several chairs. The woman was tall and slender with no fur except for the auburn tresses flowing from the top of her head. She ladled steaming juice from a pot on the squat wood-burning stove that dominated the far wall. Behind it, on either side, were two windows. Nawry saw trees through them. One bore blushing peaches, the other was clearly the source of the juiced persimmons. The woman placed two full mugs on the table, and Nawry joined her in taking a seat.

“Your people came a long way,” she said.

Nawry took the mug in his hands and blew at the steam through his whiskers. He noticed the woman doing the same, except her fingers were pale and separate, long and slender like the rest of her, with no webbing between them. “How do you know about my people?” he asked.

“I’m one of the daughters of Glyphani’aa,” she said. “I know about this world. And your people are new to it.”

“Tell me your name,” Nawry said.

“Tell me yours,” she countered.

“Don’t you already know it?”

The woman shook her head.

Nawry dusted himself off and stood from the chair, stuck a sturdy flipper hand out and said, “Nawry, pleased to meet you.”

The woman smiled and took his hand. (His own hand felt like a roughly hewn paw to him, clasped in her delicate fingers.) She said, “Aumna, and the same. I’m sure.”

The persimmon cider was both pungent and musty. Its warmth filled Nawry from the inside out, and his fur held the heat in. “Are there other people like you here? Do you have a village?” Nawry asked.

“There’s a village about a day’s walk down the road past my house,” Aumna said. “And there are a few cottages along the way.”

Nawry tried to picture a whole village of people like the angular, narrow, mostly furless woman before him. It was funny to think of, and he wondered if a whole village of Noodlebeasts seemed equally funny to her. Before he could ask, Aumna spoke again.

“The people aren’t like me though. They are my people, but I’m not one of them.”

Nawry didn’t understand, but since Aumna chose to be vague, it seemed indelicate to him to press the point. Besides, if he visited again — and he hoped to — or explored further, he’d find out what she meant on his own. At least, Nawry thought he would.

As the winter progressed, Nawry found himself traveling through the thickets to Aumna’s grove more and more frequently. So much cold blew against the Noodlebeasts’ rock houses from over the blustery ocean; yet, the seaside air gave way to inland warmth the moment Nawry emerged from the brambly thicket. And the trees there held stubbornly on to their autumnal leaves. It was a haven from his own home, and a delicious secret.

At least, until he started to paint it. Nawry sketched the paths and gardens from memory, filling them out with richly colored paints. He was particularly proud of his portrait of Aumna.

Aunt Jeminee admired his new works, but the younger Noodlebeasts were losing interest in him. Nawry spent too much time wandering the woods on his own for their taste, and he found himself excluded from their latest games. Of course, this made for a vicious cycle, as the more Nawry felt excluded by the other youngsters, the more he sought solace at Aumna’s cottage.

There was always hot cider for him there — sometimes peach, sometimes pumpkin, but his favorite remained persimmon. And, often times, there were guests to listen to, from the village down the road. They came to Aumna’s house and sat at her table; they told her about their lives and asked her advice. And they always brought her gifts from the village.

Nawry couldn’t figure out what Aumna had meant by her words that first day — the people aren’t like me. They looked like her. Tall and slender. Individuated fingers and narrow necks. Bare-skinned faces and trailing tresses from only the tops of their heads. Yet, there was a difference. A way of holding herself — a regality — a presence possessed Aumna, and the others didn’t have it.

Nonetheless, for all her mystery and hospitality, Aumna was a poor substitute for friends his own age. Nawry began to feel like a child at the grown-up’s table, and the frequency of his visits waned.

Then spring touched the world. And Nawry met Kassy.

Continue on to Chapter 2…

Read more stories from Commander Annie and Other Adventures:

Read more stories from Commander Annie and Other Adventures:

[Previous]