by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Sorcerous Signals, February 2014

The carousel turned, and Artie watched the ponies go by. He shifted his weight as he sat on the green, metal frame bench. It was one of many around the edges of the giant, window-walled room that housed the carousel. Artie was beginning to think that he should upgrade the benches. These ones looked nice, but they weren’t easy on an old man’s back.

Not that the children and their young parents who came to the carousel seemed to mind. Perhaps Artie would simply buy himself a nice cushion and bring it with him when he wanted to sit and watch his ponies.

Each of the ponies had a fancy name, painted in careful, cursive letters on a placard hanging above it. Silverina Starspire. Tigerella Jungle Queen. Tuffington Cupsworth. Artie had made up each name himself and painted the letters by hand. But, he thought of them all by simpler names. Silly Girl. Tiger. Worthy.

Silly Girl with her flowing white locks and silver horn was always popular with the children. So was Tiger. The bold orange blazes that cut stripes across her black mare’s body attracted boys and girls with adventure in their hearts. Artie liked to watch and see which children picked which of his ponies. Many children simply took the closest steed, but some had their hearts set on a particular one. He’d watched one girl ride the carousel five times one day, standing back in the line and waiting for an entire go if Froggy — the green pony with freckles and yellow hair — was already taken.

Artie’s favorites were the children who picked Worthy. It didn’t happen often because Worthy was a simple horse, the first Artie had ever carved. Brown eyes, brown body, and a curly brown mane. If Artie saw a child pick Worthy — truly pick him, not just ride him because he was the only horse left –, he made a point of seeking out the child’s parent afterwards with a pair of free tickets. He wondered sometimes if he should fancy Worthy up — paint his mane a brighter color or give him a unicorn’s horn. But Artie couldn’t do it. Worthy would have to make do.

As Artie watched the carousel today, he thought about where on the wheel he could fit in a new pony — which of the old ponies that he hadn’t replaced yet with a carving of his own would be next to go. For he could tell it was time to carve another horse.

He’d noticed the gray shimmer, like smoke or a cloud, in the corner of the carousel room a few weeks ago. He didn’t approach it or try to look at it straight on, but he cast the gray shimmer occasional glances. It moved around, mostly hiding under the benches. Over time, its shape had grown clearer and Artie could finally tell what it was.

The ghost of a sea otter.

Artie kept an eye on the little fellow for the rest of the afternoon. When the evening light slanted over the sea and cast long shadows through the wall of windows, Artie closed the carousel up. He sent home his two employees — a pair of local high school kids, one to sell the tickets and another to control the carousel. They could clean up tomorrow.

Alone in the large window-walled room, except for all the horse statues and the shimmering gray otter spirit, Artie said, “I’m going to my workshop now. I’ll leave the doors open, though, so I expect I’ll see you soon.”

The otter spirit loped after Artie. Its ethereal back bunched up, and its wide tail swayed from side to side. The door to the carousel room stood open behind them.

Salt breeze from the beach blew into the still room while evening darkened to night outside. When the first star appeared in the purple sky, the stillness in the room changed. Wooden bodies that had stood stiff all day shifted, flexing muscles, drawing in breaths through carved nostrils. Each of the ponies took its own time, stretching out legs that had posed in frozen prances, and stepping down from the wheel of the carousel. They left strange empty spaces on the carousel between the old ponies which Artie hadn’t carved and which yet stood still as statues, and they left gaps in the gold metal poles that were their anchors during the day.

The ponies spilled out of the carousel room, prancing in their carnival colors on the sand of the nighttime beach. Two of them, though, headed straight for Artie’s workshop.

Blocks of wood in various sizes were spread around Artie’s worktable, but he hadn’t begun carving. The chisels were lined up in a row, untouched. The tool in his hand was a colored pencil. An entire rainbow of the pencils were strewn around the sheet of paper in front of him. On the sheet, he’d drawn a pony with a purple, green, and yellow striped mane; a white body with little red polka dots and large orange ones; and a golden saddle with a silver bridle. The pony’s front legs reared up, and it held its head at a jaunty angle.

“Colorful,” a melodic voice intoned over Artie’s shoulder.

The old man turned to see Silly Girl with her shining white fur standing beside him. Warm breath from her nostrils puffed at his neck. Artie reached a hand up and stroked her muzzle. “Indeed,” he said. “Sea otters have always made me think of clowns. Something about their foolish manners, and their wide noses.”

“You should give it a neck ruff then,” Silly Girl said. “Clowns wear those.”

“I like that,” Artie said, smiling. He turned back to the drawing and sketched in a black neck ruff with purple stars.

While Artie carefully filled in all the corners of the stars, Silly Girl turned to look at the sea otter spirit. The gray otter shape had been touching noses with Worthy. When it saw Silly Girl pointing her horn its way, though, it bobbed its head and turned in a quick circle, almost dissolving from its otter shape back to an amorphous cloud.

“You’ll be the most fancy one of us, Otter,” Silly Girl said, her voice sounding imperious.

“Jealous?” Artie asked, not yet looking up from his sketch.

“No,” Silly Girl said, but she clearly meant yes.

“Don’t worry, Silly Girl,” Artie said. “You’re still my only talking companion.” He knew she feared the day that another human ghost would find its way to him and join the ranks of the ponies on his carousel.

Silly Girl had been an important woman during her human life. A politician or lawyer. At least, that’s what Artie gathered from her somewhat muddled memories. By the time she’d found him, Artie figured she’d already been a ghost for several decades. And her accent suggested she’d traveled a long way to find him, probably all the way across the country. Her deep southern accent and antiquated mannerisms faded with time. Her air of confidence had not. She was the only unicorn and clear leader of the ponies on his carousel.

“Will you take Otter to meet the others?” Artie said to Silly Girl. “I think he’s ready now.” Artie didn’t know if the otter ghost was male or female, but he knew that the carousel could use another stallion. So, Otter would be male in his new life. If that was a change, he’d get used to it. All of the ponies, except for Horse, had had adjustments to make in getting used to their new bodies.

Artie tried to make it as easy as possible for his ponies, giving them bodies that he felt suited them. He made Eagle a pegasus; he’d given Tiger her familiar stripes; Froggy was green and freckled; and Worthy had exactly the coloring of the chocolate lab who’d been Artie’s best friend until the day he had passed away. However, none of his ponies had been horses in their previous lives except Horse. So, none of them looked as comfortable — as much at home — in their pony bodies as Horse did.

Artie watched as Silly Girl walked over to Otter. She stepped lightly, holding her head bowed. The otter ran to the back of the room and turned in circles, afraid of her approach, but Silly Girl’s horn glowed, an almost imperceptible change in its silver shine, and the otter’s fear seemed to subside. Artie couldn’t tell exactly what magic Silly Girl held in her horn. She liked to keep some secrets from him. But he suspected she could talk to the other ponies — mind to mind — and even the ghosts before they became ponies.

“Come on, Otter,” she said. “We’ll start with Bunny and Rabbit. I don’t think they’ll scare you as much as Tiger does.”

“Wait,” Artie said, before the shining white unicorn could lead the hazy gray otter shape out of the workshop. He picked up his drawing and held it out for the otter to see. “Do you like it?” Artie asked.

The otter’s expression didn’t change, but Silly Girl said, “Don’t be so insecure. Of course, he likes it. Now get to work so Otter doesn’t have to stay a ghost any longer than absolutely necessary.”

Silly Girl had told Artie about how cold and nauseous she’d felt during her entire time as a ghost. It was a terrible experience, and she wouldn’t wish an extra minute of it on anyone. Even a pony who was going to be more “colorful” and “fancy” than her. She had a good heart.

Worthy stayed in the workshop with Artie. The old man arranged blocks of wood on his worktable, deciding which pieces he would carve into which parts of Otter’s anatomy. Meanwhile, Worthy leaned his warm, heavy body against Artie. “Good boy,” Artie said. “We can go for a ride later.” He always went for a ride with Worthy before going to bed for the night. He knew the ponies stayed up later than him, but an old man needs his sleep. Already yawning, Artie changed his mind. “Know what, Worthy? I can work on this tomorrow. Let’s go for our ride now.”

Outside of the workshop, Artie climbed up onto Worthy’s back and settled into the simple, black saddle. He could see Silly Girl, Rabbit, and Bunny already on the beach.

Silly Girl’s horn was glowing in the night, and Rabbit and Bunny were prancing. He couldn’t make out the ghost shape of Otter in the dark, but he thought Rabbit and Bunny must be playing with him. Silly Girl was right to introduce Otter to them first.

Artie rode Worthy along the beach, right at the edge of the waves. Artie remembered when he and Worthy would play fetch here. He would throw the tennis ball into the surf, and Worthy would chase after it, bringing the soggy green ball back to him, held in a gentle mouth. Man and dog. Now they rode together. Man and horse. It was different, but Worthy was still his best friend.

“You brought all these friends to me,” Artie said, patting Worthy on the neck. “I would never have known to build carousel horses for them if it weren’t for you.” Artie thanked God and luck every night that, in his grief over Worthy those many years ago, he’d carved a carousel horse and painted it with Worthy’s coloring. Whatever mystery of nature and divinity had caused Worthy’s ghost to enter and animate that wooden body had changed everything about Artie’s life.

Worthy and Artie rode to the rocky outcropping that ended their stretch of beach before turning back. At the end of the ride, Artie said goodnight to his ponies and settled down to sleep on the cot in the back of his workshop. He returned home less and less these days, preferring to sleep in his workshop.

After he finished building Otter’s new body, perhaps his next project would be to make his workshop a more comfortable apartment. It already had a small bathroom with a sink and toilet, but a shower and better kitchen facilities than the single hotplate would be nice.

Artie heard the hoof falls and whinnies of his ponies blend with the sound of the waves on the beach as he fell asleep. Sometimes Silly Girl sang a lullaby about the bayou, but he could never be sure if it was only a dream.

When the morning light woke Artie, he climbed up from his cot and stumbled, still clumsy with sleep, to the open door of the carousel room. Tiger, Bunny, Rabbit, Froggy, Eagle, Horse, Worthy, Silly Girl and all the others stood as still as statues on the tented wheel. They were statues. All day long.

Artie shook his head. His life was hard to believe sometimes, but the gray shadow of Otter, hiding in the corner, served as proof. Cold and nauseous and waiting. “Come on, Otter,” Artie said. “The carousel won’t open for hours yet. Let’s go work on your body.” Besides, he thought, you’ll spend plenty of days here at the wheel once you inhabit it. For now, you can spend the day with me.

Artie worked day and night, chipping away at the pieces of hard maple wood that turned into hooves and legs, muzzle and ears, strong back and flipping tail. Curling wood chips littered the floor, and the smell of sawdust mingled with sea salt in the air. None of the pieces came out exactly as Artie planned them. Sometimes the wood grain fought with his tools, and he had to adjust his plans, hiding his mistakes or marveling in the beauty that his tools uncovered, pre-existing in the wood.

As the weeks wore on, the heat of summer began to cool into early fall. Artie felt the ache in his hands grow as they tired from daily sawing, chipping, sanding, and re-sanding. When all the pieces were done, though, he fit them together with dowels and glue. Finally, piece by piece, they came together, forming the hollow horse-shape that would eventually become Otter.

The plainly wooden horse stood in Artie’s workshop for a week while he waited for his hands to recover. He would need a steady hand to paint it.

When he was ready, Artie brought out an extra bright light to shine on the wooden horse. He could carve, at least partly, by feel, but he had to paint by sight. The brightly colored paints he used were oil based. The gold for the saddle, however, was actual gold leaf in sheets as thin as a human hair. The silver for the bridle wasn’t real silver as that would tarnish too easily. Instead, it was made from aluminum.

It took less physical effort to paint the horse than it had to carve it, but the painstaking detail and Artie’s aging eyes made it the hardest part.

When the final coat of paint dried, Otter’s body was the most beautiful carousel horse Artie had ever carved. Of course, he thought that about each of his ponies when he really looked at them.

Eagle liked to watch Artie do the painting. So, it was her and Worthy at his side on the day when he finally declared Otter’s body finished. “What do you think?” he asked, standing back from his masterpiece. The newly carved carnival clown pony reared in its frozen pose in front of them. The polka dots and stripes in the mane were so much more colorful in real life than they’d been in Artie’s sketch. His chest swelled with pride.

Worthy butted his head against Artie’s arm, affectionately approving. Eagle stamped her front hoof, stretched out her wings, and reared her hooves into the air herself.

“I’m glad you approve,” Artie said. “Shall we find Otter?” But, of course, that wasn’t necessary. The shadow of ghostly gray that was Otter’s ethereal form already sat in the doorway of the workshop. Artie didn’t know how, but the ghosts always knew when their bodies were done. Perhaps the same force that drew them to his carousel called them to their wooden forms.

Artie hoped one day that he would feel that call. The unicorn body that he’d carved for himself was already waiting, obscured behind a slat of wood, in the back of his workshop. He didn’t know what caused some animals — and people — to turn into ghosts when they died. And he didn’t know why some of them came to him. But, if he had anything to say about the organization of the universe, when he was called to leave this human body some day, he would take a gray ghostly form — like Otter now held and like each of his ponies had come to him in — and he would return to his carousel.

Artie closed his eyes thinking about it, and, when he opened them again, the stiff shape of the clown pony had relaxed and put its front hooves down. With soft white fur and cheerful polka dot spots, Otter came over to Artie and nuzzled his new muzzle against the old man’s face. Artie laughed and smiled. “How do you do that?” he asked. “I’ve made so many of you, and, still, I can’t believe when another one comes to life.” He put one hand on each side of Otter’s long equine face and looked him steadily in his liquid brown eyes. “Are you happy, Otter? Will you come to life again and again? Every night?”

The melodic voice of Silly Girl spoke from behind them, “Are you worrying again? You’re not crazy, unless I am.”

“You, Silly Girl,” Artie said, “are a carnival unicorn who thinks she used to be a woman from Louisiana. I don’t think you should be claiming to know what crazy is.”

“Fair enough,” Silly Girl said, but when Artie turned to look at her, she tossed her mane in a way that left no uncertainty: she stood by what she had said.

“Well, Otter,” Artie said, “we have a tradition here. When a new pony joins the wheel, we all ride down the beach together. Would you be kind enough to let me up on your back?”

Otter whinnied and threw his head back. His ears flicked, and he lifted his hooves in a dancing step.

“He’s still getting used to his new body,” Silly Girl said.

Artie nodded, and he waited for Otter to settle down. When his hooves stilled, Artie took Otter’s silver bridle in his hand and led the new pony out of the workshop and down to the sand. All the other ponies followed.

During the weeks that Artie had spent building Otter’s body, they’d all gotten to know the spirit that was now inside. But this was their first introduction to the cheerful, goofy, polka dotted pony who would join them on their wheel tomorrow.

Rabbit and Bunny came up to him first. They bumped their noses against his and shared a snort of warm breath. Then Tiger pranced her way over, somehow managing to communicate a jungle cat’s stealthy prowl, even while sporting equine legs. She held her distance, eyeing Otter, but she seemed to approve. His colors were as bold as hers, albeit in a different style.

The ponies pawed the sand with their hooves and bobbed their heads. Artie was sure they could communicate with each other somehow, possibly through the simple understanding that while they had all come here different they were all the same in one important way. They were all ponies of the same carousel.

When Silly Girl told Artie they were all ready, he mounted Otter. He felt Otter’s body shift beneath him, and, instead of urging Otter to take off down the beach, Artie let his new pony find his own footing. He walked to the water’s edge and let the wavelets there break against his hooves. Salt water slid over the sand beneath him.

“It must be different to feel the sea against a horse’s hooves than it was to float in it as an otter.” Artie’s voice was quiet, but he could tell Otter had heard him. “I know that Eagle still wishes she could fly,” Artie said. “I imagine, if I’m ever lucky enough some day to join you, that there will be things that I’ll miss too.”

Artie sat on Otter’s back, stroking his long neck and rainbow striped mane. The moon shone down and reflected in the glassy waves. Otter’s white face reflected there too.

Artie looked down the shore and saw the other ponies waiting for them, dancing in the shining wet sand and sea foam. Artie combed his fingers through the green, yellow, and purple hair of Otter’s mane. He’d made the best body he could for Otter; now it was up to Otter to find peace with it. “Shall we go?” he asked, squeezing his knees gently against Otter’s sides.

Otter whinnied, and, finally, his reverie was done.

Artie and Otter cantered down the beach toward the others, and Otter’s legs stepped high. He raised his nose, and shook his mane. He pranced and danced like the clown Artie had made him into — like the clown Artie had guessed he already was.

Eagle reared and flapped her wings at him. Rabbit, Bunny, and Froggy hopped around him in lighthearted gaiety. When they all set off down the beach, Worthy rode close by Otter’s side. And, although Artie couldn’t be sure over the sound of the wind in his ears, he thought he heard Silly Girl singing a song.

An entire carousel’s worth of ponies rode together down the moonlit beach, and, tomorrow, they’d ride all day together again, in circles filled with smiling and laughing children.

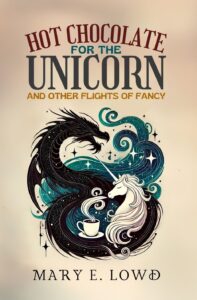

Read more from Hot Chocolate for the Unicorn and Other Flights of Fancy:

Read more from Hot Chocolate for the Unicorn and Other Flights of Fancy:

[previous][next]