by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Northwest Passages: A Cascadian Anthology, September 2005

His confidence drew her to him. The gleam in his eye said “I can take on the world,” and she believed it. Here was a man who could not fail. She was fascinated, and her fascination endeared her to him.

Michael introduced them, but neither Joan nor Leland bestowed a second glance on Michael all night. Their eyes and conversation were reserved for each other.

Five months later, Joan and Leland were living together in a penthouse apartment downtown with a view of Mount Hood, functioning smoothly as a couple. Michael came over for dinner every second or third night. Their home was his second home, and he was best friend and confidant to each of them. Proud of his role, he boasted loudly of having introduced them. He couldn’t find a girl of his own, he’d say, but he sure could find them for his friends, couldn’t he? Leland would concur, but Joan would just smile and get Michael a second drink.

“When are you doing the parents thing?” Michael asked one night. “I know you’re thinking of getting married…”

“So, we better hurry up and get our parents involved? Or else they won’t pay for the wedding?” Leland joked.

“That’d be a shame,” Michael said. “With our company topping the market, you couldn’t possibly pay for a wedding yourself.”

Leland grinned. “We’re only up there, kid, because I have such a competent engineer.”

Michael bowed his head to the compliment, and the men clinked glasses. Though, they all knew it wasn’t Michael’s engineering that carried Doohan Gadgetry to the top. Perhaps it kept them there, but Leland’s uncompromising entrepreneurship was the instrumental ingredient.

“Actually,” Joan said, “we already have done the parent thing.”

“That’s great. How’d it go?”

“Well, Joan’s parents loved me.”

“Who wouldn’t?”

“I mean it. Her dad and I really hit it off, and her mom’s got the best, driest sense of humor I’ve ever heard. Better than yours, Michael.”

They both turned to Joan. She hesitated but said only, “Leland’s mother was very nice.”

“It’s just my mom,” Leland added, “Dad died when I was a little guy.”

“I remember,” Michael said. “Was your brother there?”

Leland laughed right out loud. “What a guy! Michael, I don’t know what I’d do without you.”

The interchange stayed at that, until Leland retired to his home office for the night. He had work to catch up on, a meeting to prepare for in the morning, plenty to keep him busy. Joan saw him to his book lined cell, kissed him on the cheek, and closed the solid oak door behind him. As she did, she heard him muttering, and she thought she caught the word “brother.”

“What was that about?” she asked Michael, back in the living room. “Does Leland have a brother?”

“He likes to deny it. I think they’re mad at each other. I met him a long time ago… Before Leland’s first company crashed. I was an engineer for him back then too.”

“Leland had a company crash?”

“He doesn’t like to talk about that either. He doesn’t like to talk about failing.”

“He gives off the impression of a man who couldn’t fail… Or, at least, a man who never has.” Joan sipped her drink. “You’d think it’d scar him.”

“Well, that’s probably why he doesn’t talk about it. He’s keeping it out of his mind.”

Joan and Michael chatted on, finishing their drinks. Come two o’clock that morning, Joan finally saw him to the door. She grew quiet, and leaned against the doorframe in such a way that Michael could see something was wrong.

“What is it?” he asked.

“Leland’s mother didn’t say anything when Leland talked about growing up alone… How hard it was, just the two of them, after his dad died.” Joan played her fingers along the doorframe. Then she stopped and looked Michael square in the face: “Did you ever meet Leland’s mother?”

He shook his head.

“She looked sad. But it was a cheerful sad… The kind that hides its tears.”

Michael touched Joan’s cheek and wished her goodnight. He was right, though he did not say it: a mother would be sad when her sons did not speak. But, Joan wondered if that was all. Why did she play along? If she were Leland’s mother, she’d be angry at her sons’ childishness. She wouldn’t pretend to have one son at a time, even if her sons pretended not to have brothers.

* * *

Joan kept hoping to talk with Michael about Leland’s past again, but she never got the chance. One week later, Michael was hit by a car crossing Burnside near Powell’s Books. Leland was there, browsing the new window displays. He looked up from a magazine about the latest Fortune 500s to see a ratty old Jaguar plow into Michael.

He couldn’t have done a thing. Yet, Leland blamed himself, and Joan got to see what happens when the man who can’t fail finally does. He breaks.

The daring, fearless, entrepreneurial spirit that carried Leland and his company to the top abandoned him. He claimed that Doohan Gadgetry couldn’t get by without Michael, but in truth, there were plenty more engineers. It was the fearless lion who once was Leland that his company couldn’t get by without. He questioned his choices, lent credence to his second thoughts and crippled himself with self-doubting indecision.

Joan cried too, and found solace in their shared grief at night. But she was seeing only the half of it: At work, she still functioned, crying only at home. She felt like a hollow shell, but it was just that: A feeling. She carried on.

True understanding waited until she came home one night and found Leland sprawled on the floor, leaning against the couch: He was gripping an orange plastic medicine bottle.

“I have to make it go away,” he said. He looked like a man bitterly drunk, but he was only drunk on tears.

“What have you taken?” Panic tinged her voice. Joan took the bottle and read the label.

“I haven’t taken it yet… I was waiting for you.”

* * *

On her second date with Leland, Joan had asked him, “What was your childhood like?”

“Good. Happy,” he laughed.

“Tell me a story from it.”

“Okay,” he said. “I entered a kite contest once. I spent a week designing and building a kite shaped like a fish. A giant, silvery, scaled fish, flying in the sky. The scales had to be cut out and glued on individually. I remember getting a cramp in my neck, hunched over my work table for hours. I had to get it just right.”

“Did you win?”

“I don’t remember.” He laughed again. “It was beautiful though. On the test run, it positively sparkled… looked like it was swimming in the sky. I’ll have to show you sometime. If I can ever find it…”

Joan had smiled at the time, but now the memory took on an ominous tone.

A lot of Leland’s childhood had seemed hazy, but Joan’s memories from that age weren’t so good either. When they got to talking about Leland’s career, the stories were of one success after another. Up and up and up. Leland lived in a can-do world, and Joan had loved being swept up into it.

But now she had to face the price.

* * *

“You have taken it,” she said. “You took it after your company crashed, and after you fought with your brother… When else? How many times?”

“I can’t remember.”

“Of course not.” There was bitterness in her voice.

“I mean, I can’t remember the number. Every time. I take it every time.”

“So you do have a brother?”

“Yes.”

“Do you remember him?”

“I remember. I remember! I remember. And I want to forget. The pain reminds me. Brings it all back. And now Michael dying… I can’t take that. I can’t suffer through this one with you. If I do, it will bring them all back. All the memories. I’m just starting to taste them again. On the fringes of my mind. My life is riddled with them.”

“All our lives are.”

“Not like mine. Not like mine. My dad… my senior prom… getting kicked out of Catlin Gable… all the money trouble…” Leland flipped through memories seemingly too painful for him to recount. He latched onto an easier one: “That kite contest… when I was a kid? I lost that contest. I dropped my fish-kite in the mud and everyone trampled it. It was ruined, and that’s why I can’t find it. I lost, and it was my own fault too. Clumsiness. I can’t remember things like that. I can’t afford to remember things like that. How would I go on?”

“We all go on. We all fail, and we all go on.” She paused, “We’ll go on together.”

“No.” He shook his head. “No, no. But you can take it too. We’ll forget together. It’ll all be the same as before.”

“Except without Michael.”

“That can’t be helped now.”

Joan looked at the label on the bottle: “Amnesia Inducing. For medicinal uses only. Keep away from children and those with memory disorders.”

How could she comfort him? He was feeling the pain of every failure, every loss, every bad moment since early childhood. Scrapes and cuts that should have been kissed better years ago bled freshly now. The sting of disinfectant in a million tiny wounds, covering every last inch of your body could kill you, she thought. Joan handed him back the bottle. “What will you forget?” she asked.

“Just the parts that hurt. And the bottle.” He shook the orange canister, rattling the pills inside. “I only remember these when I need them. Pain makes me remember.”

* * *

Joan still missed Michael. She was sad, all the time, and Leland could never figure out why. He’d smile at her. Tickle her to make her laugh. Then she’d be cheerful, a thin cheerful stretched across something hidden, horrible inside. When she spoke of Michael, Leland assumed she meant a childhood friend, someone she’d known before he met her. But Leland didn’t mind. Her sadness made him think of his mother, the dear creature she was. Dear creatures they both were. Now.

“Where’s that old kite I made?” Leland asked his mother when they visited her in her house in Ladd’s Addition. “Remember? I made it to look like a fish? A fish-kite?”

“I remember,” Mrs. Doohan said through thin lips, with a tender irony Joan found comfort in understanding.

“I want to show it to Joan.”

“Try the attic, honey.”

Joan stayed downstairs, talking with his mother. The two women let Leland rifle through the attic, reveling in his cherry-glow memories alone.

“Will you tell me about Leland’s brother?” Joan asked and could tell the question startled Mrs. Doohan.

“Would you like some tea?” Mrs. Doohan didn’t wait for an answer. “I’ll get it,” she said and busied herself with cups, saucers and heating water.

“Won’t you talk about it?” Joan asked, following her to the kitchen.

Mrs. Doohan placed her hands on the rim of the sink and looked out the kitchen window. “What good would it do you to know? He doesn’t, and if you tell him… No. No. Just have some tea.”

But Mrs. Doohan reluctantly let Joan draw the story of Leland’s past from her. Her other son, Geoffrey, was much older than Leland. After their father died, Geoffrey had tried to be a father figure for Leland. He took his little brother to the park, the zoo and on fishing trips. During one trip to the park, Leland fell from the upper branches of tree, but instead of falling straight to the ground, he’d gotten caught and had hung there, twisted and hurting, with the wind knocked out of him until Geoffrey was able to find help to get him down.

Geoffrey felt horrible, but his guilt was nothing to Leland’s lasting trauma. Nightmares woke him and day-mares haunted him. Geoffrey tried to make up for it. He was a researcher at a cutting-edge lab, and their newest product was a memory drug. Geoffrey hoped it could dull the pain, lessen the power of Leland’s memory.

A normal course of therapy involved taking the pill many times to fully eradicate the complicated network of memories in an adult brain. Of course, in retrospect, Geoffrey realized a child would only need to take the drug once or twice to fully forget. At first, no one realized that Leland was faking it; he didn’t need the drug any more, but only pretended he did. By then, he’d built up a hidden stockpile. A poor test score – a pill; an argument with his brother – a pill; a lost contest – a pill. Leland lived the perfect, happy childhood.

After that, the drug became available on the black market.

Geoffrey begged Leland to give it up. They fought for years. Leland forgot his pains, and Geoffrey reminded him. “Don’t fill your life with empty spaces,” Geoffrey had said.

Leland retorted, “Stop filling the erased parts of my life back in!” Eventually, Leland forgot Geoffrey too.

In the end, the pills could never wipe Leland’s mother and childhood home away, not like they had his brother. So, Leland would turn up at her door again, ironically, stubbornly, remembering the labyrinthine way through Ladd’s Addition. They’d have dinner, and Mrs. Doohan learned not to talk of certain things. Or else, they’d start again. Clean slate.

“He’s a responsible, dutiful son,” his mother said.

“That’s what he’d like to think. That’s what he does think. You let him.”

“He’ll be good to you,” Mrs. Doohan said. “He’s always kind.”

Mrs. Doohan was right, but it was not enough.

* * *

In the weeks that followed, Leland worked hard to cheer Joan, and when he failed, he accepted it without complaint. He never yelled, or stormed, or blamed her for her tears. He waited them out. Joan couldn’t take that. It made her die inside, to see him watching the clock, patiently counting the minutes until she dried her tears. So, she’d cry in private — in the bathroom, at work, wherever Leland couldn’t see. It was hard to miss Michael alone, but she managed.

The day Joan realized that she’d stopped crying entirely – not because she was ready, but because Leland didn’t understand – that was the day she knew.

“It’s over,” Joan said.

But in Leland’s world nothing good ever ended. He couldn’t understand.

“You need space,” he said and helped her pack. “It’ll be good for us, to be apart for a while. I’ll call you in the evenings, okay?”

His confidence never left him when she refused to give him her number. In his mind, they were a couple, and that could never end. Like his mother, she’d always be there for him.

“Then, you’ll call me,” he said. “When you’re ready. I’ll wait.”

* * *

The next time Leland saw Joan, months later, they passed on the street. It was the intersection by Powell’s where Michael had died, and there was not the faintest gleam of recognition in his eye. He tipped his hat, but strode on by.

Joan, however, stumbled and caught her balance, leaning against the bookstore wall. Her heart was still healing, and though she expected he would forget her, she wasn’t ready for the reality. Had it all been pain for him? Had every last piece of her been wiped away?

Yet, he looked the same, was the same, as the first day they met. He didn’t remember her. He didn’t know he’d loved her. There was nothing of her left in him at all.

But he still lived inside her, and she cherished the time she’d had with him. His fragile perfection endeared him to her even as it renewed her faith in her choice. It had been right to leave him. The fires and floods of emotion that Leland avoided fortified Joan. And she locked her part of him, the part of his life he gave her without even keeping a copy for himself, away in her heart.

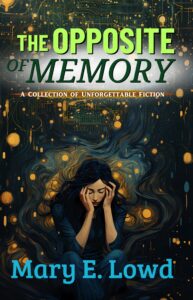

Read more stories from The Opposite of Memory:

[Next]