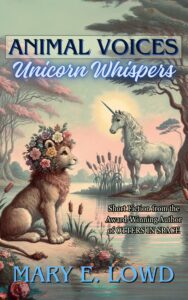

by Mary E. Lowd

Originally published in Dancing in the Moonlight: Rainfurrest 2013 Charity Anthology, September 2013

The eggs never hatched. Henrietta and all her coop-mates laid eggs every day, and every day the Coopmaster came and took the eggs away. No baby chicks. Henrietta had so much love in her feathered breast and no one to spend it on.

Only nine inches below the slatted floor of the coop, a cold and hungry litter of fox kits waited for their mother to return. One by one, the kits closed their eyes and fell into a patient sleep. Their breathing slowed. Their hearts slowed too. Still, the mother did not return.

But one kit was not patient. His heart beat fast, and his nose twitched at the smells that drifted down to him from between the wooden slats. The musty, dusty, warm-blooded smell of chickens tantalized him, filling his nostrils.

While his littermates waited for a mother that would never return, losing themselves into the sleep that becomes death, the impatient kit followed his nose out from their den and into the chicken coop above. There, he found a new mother.

Neither Henrietta nor any of the other chickens in her coop had seen a fox before. Chickens don’t often live long after seeing a fox, and the last massacre of that particular hen house had left no survivors to tell the tale. The Coopmaster had ordered replacements from the local feed store and raised them from eggs. None of them knew the haunted history of their home. Thus, when Henrietta saw a small, pointy, red-furred face peek into the coop, she wasn’t frightened. In fact, her first thought was, “Why, what lovely plumage! I do believe it’s exactly the same shade of red as my own!”

Henrietta was smitten. She was the only red hen in her coop; all the others sported black, white, or checkered feathers. Clearly, she and this little creature were meant for each other. She would call him Henry.

And so Henry became a chicken. He was invited into Henrietta’s nest where she sat on him, keeping him warm with her thick, soft feathers. All the hens doted on him and offered him all the grain a growing chick could want. But Henry wasn’t a chick, and he didn’t want grain. He wanted eggs.

The eggs weren’t serving any better purpose — in fact, none of the chickens knew why they laid them. Day after day, they laid the mysterious, pearlescent objects, and day after day the Coopmaster came to take them away. So, when Henrietta’s little red-furred chick began to crack eggs and lick out their viscous, slimy insides, none of the hens begrudged him. Better, they thought, that Henry eat the eggs than that the Coopmaster steal them. That dirty thief!

The chickens treasured Henry and hid him carefully from the Coopmaster. If the Coopmaster stole their eggs, there was no telling what else he might steal, and they couldn’t stand to lose their baby.

For his part, Henry reveled in the attention from his coop full of clucking new mothers. He loved the warm pressure of Henrietta’s weight perched on top of him, pressing him safely into the nest as he slept. He enjoyed the gentle tugs and tickles as various chickens took turns preening his fur with their beaks. His life was a blur of warmth and touch and safe, comfortable smells. And, of course, the eggs were delicious.

As Henry grew, the chickens began to speculate about him. He looked so different from the rest of them. He hadn’t changed shape as he grew, sprouting wings and talons like they’d expected. He’d merely grown larger and sleeker. His smell was sharp and dangerous. Terribly exciting! Why, it made their hearts flutter!

Eventually, one of the youngest hens — Calliope with the loveliest, downiest, white feathers — suggested that Henry might not be a hen. He might be a rooster.

All the hens were atwitter at the idea. A rooster! In their hen house! Oh my! Some of the more romantically minded hens had dreamed of meeting a big, strong rooster some day.

A black-checkered hen named Dorrit, the fattest in the coop, swooned at the very idea. The other hens had to fan her with their wings until she recovered, rousing from her faint only to exclaim, “Oh Henry! You are the handsomest young rooster I could imagine!” Then she turned all shy and hid in her own nest with her head tucked under her wing for the rest of the day.

After that, the chickens began to court their young squire. Some sang songs to him in warbling voices; others followed him around, plying him with eager compliments. As always, Henry loved the attention.

Dorrit plucked flowers from the garden to bring Henry. He was quite flattered, but he had no use for flowers.

Calliope dug up worms for Henry. Those tasted funny and squirmy in his mouth. They weren’t rich and yolky like the eggs, but their flesh burst satisfyingly under his teeth. Henry approved and asked Calliope to teach him worm-hunting. As the two of them spent more and more of their afternoons together, hunting worms and gossiping, it became clear to all the hens that Calliope had gained Henry’s favor.

At a word from Henrietta, the other hens stopped courting her son. If he’d chosen Calliope, there was no need to confuse the young couple. No, indeed, it was time to give them space to get better acquainted. And time to prepare the wedding!

The big day was set for a week hence. Under Dorrit’s direction, the chickens plucked flowers and vines from the garden to decorate the coop appropriately. At Calliope’s suggestion, they gathered worms for a special feast. And Henrietta arranged for them to build a new, larger nest for Henry and Calliope to share, discreetly hidden at the back of the coop, behind a screen she wove out of straw.

While the rest of the hens worked industriously on the wedding, Calliope strolled with her handsome husband-to-be around the edges of the farmyard. His presence close beside her made Calliope nervous, and her presence close beside him made Henry’s heart pound with anticipation.

Calliope’s white-feathered body was plump and tempting; her neck slender and appealing. Henry felt an urge, deep in the pit of his stomach, to nuzzle her neck, caress that plump body with his muzzle. He didn’t understand the feelings, but they were strong and exciting.

On the night before the wedding, Henry confessed his confusion to Henrietta. As any good mother should do, Henrietta assured her son that his feelings were completely normal. On the morrow, it would all make sense. “Don’t worry,” she said. “I know you love Calliope, and you’ll make her a good husband. As you are a good son. And a good rooster. Just follow your instincts, and let your feelings for Calliope be your guide.”

Henry was reassured. He did love Calliope. She was far and away the cleverest of the chickens in the coop. On their walks, she’d told him many stories, sharing her insights on the world and on the political intrigue between different chickens in the coop that Henry had never noticed before. He could listen to her musical voice cluck away, filling his ears with ideas and stories, forever.

The wedding was a solemn affair. All the chickens arranged themselves in a circle around Calliope and Henry. Each and every one of them had prepared a few words to say. Chickens have a lot to say. And they all got their turns — wishing Henry and Calliope happiness, reminiscing about old times, and making promises to support the two of them in their future together. And, of course, hoping for them to have many children.

Then the newlyweds went inside to enjoy their newfound marital bliss while all the other chickens stayed outside, to give them their privacy.

The new nest was made from the freshest straw and had been lined with fragrant flower petals. It was plenty large. Calliope roosted in the middle, nervously preening her neck feathers, and Henry curled his body around hers.

“My bride,” he said, pressing his muzzle against her breast.

“My love,” she clucked, tracing the tip of her beak down the curve of his ears. A tingle of excitement shot through him at the touch.

Henry opened his mouth a little and breathed softly against her. Calliope’s feathers ruffled under his breath. He touched his teeth to her neck in a touch as soft as hers. He nipped lightly, playfully at her like the kit he used to be, and he felt her heart race under the breast pressed against him.

Calliope, suddenly, held herself very still. She didn’t understand the feelings racing inside of her. She expected to feel love for her husband. Instead, she felt only fear.

Henry, however, was unaware of the change in his bride’s feelings. His own feelings were running high, and everything in him said to press himself harder against his wife. He tightened the grip of his jaw, feeling his teeth press into her plumage. A hunger inside Henry roared for him to bite harder against her tender, delicate neck in his mouth. Overwhelmed with love for his bride, Henry followed his instincts.

Calliope began to struggle, but then her body shuddered and fell still. A satisfying crack between his teeth and the hot flow of blood into his mouth told Henry that he was doing what was right. Nothing could feel more right than the glorious taste that exploded in his mouth. He felt himself overcome with a blind urge to rampage and ravage, working his jaws until white feathers flew around him.

Henry had never eaten a meal so amazing, so succulent, so filling. Immediately, afterward, Henry fell into a deep, contented sleep.

In that sleep of satiation, Henry dreamed a disturbing dream. He was a tiny kit again, nestled under his mother hen’s feet, and he was watching all the hens in the coop fly about in a crazed, frightened flurry. “Where is Calliope? Where is Calliope! Where has she gone?” they all clucked. Every chicken was in a tizzy, and Henry felt guilty. Though, he didn’t know why.

The clucking changed, as chickens began to bock, “She’s dead! She’s gone! Someone has killed her!”

Then Dorrit squawked and flapped her wings, commanding the attention of all the chickens in the coop. They roosted around her, settling down and quieting themselves to hear what Dorrit had to say. She turned to the assembled crowd and announced, “The killer is none other than…”

Henry awoke in a fever. Although he’d lost himself in his passion, Henry knew what he had done. He’d eaten his beloved. His wife. His Calliope. His tender, tasty, delicious Calliope… Henry’s mouth watered at the memory of her flesh on his tongue. He felt power surging inside him, as if he’d finally realized who he was. He had woken up into himself for the first time and all his life was like a mad play.

Henry wanted to share his insight with Calliope, but the feelings that welled up in him at the thought of her were complex and shifting. Love. Regret. Hunger. And an insatiable desire to feel her hot blood pumping onto his tongue.

Faster than he could think, Henry’s feet carried him out of the chicken coop and into the yard. His eyes shone with a mad light as he looked, blinded with bloodlust, at the chickens who’d raised him. Loving clucks turned to screeches of horror as Henry flew at the hens.

Feathers flew in the air.

Henry tasted blood again and again, until there were no more chickens. Only a mad fox, shaking limp carcasses in his mouth, mere feathered bags of flesh and broken bones. His belly was too full to eat anymore but his tongue still screamed for the taste of hot blood.

When finally the Coopmaster came with a gun, Henry darted into the forest behind the farm. He ran through the underbrush, haphazardly dashing without knowing his way. The speckled light filtered down through the trees, dappling his red coat. And, only now, did his sight begin to clear. Only now did he realize: Calliope, Henrietta, all the chickens… were gone.

Henry found a hollow, rotting log, smelling of earth and wood like the place he was born, the place his littermates had died. He knew what he was now. And what he had never been.

The next few weeks were hard. Henry was used to living in a warm hen house, eating eggs, and listening to the friendly clucking of the hens. He was used to the feel of soft feathers and the gentle preening of careful beaks. He wasn’t used to working his paws numb, scratching out hollows in the cold dirt ground; or hunting for his food; or falling asleep to melancholy silence alone.

Henry was like the kit he had been before he found the warmth of the hen house and Henrietta had named him. Except, now he was grown, and he could take care of himself. He could find his way through the forest. He was lean and strong, a deadly predator. He was a fox again.

But he missed his chickens.

Read more stories from Animal Voices, Unicorn Whispers:

Read more stories from Animal Voices, Unicorn Whispers:

[Previous][Next]